Four years later, Haiti’s resurrection continuesPosted Jan 10, 2014 |

|

Casera Bazile’s Baptism of Our Lord mural, which he painted inside the Episcopal Diocese of Haiti’s Holy Trinity Cathedral in Port-au-Prince, in 1951 was one of three of the original 14 murals which, in part, survived the Jan. 12, 2010, earthquake that leveled the cathedral. Since this photo was taken about five weeks after the quake the murals have been removed and stored. Photo: Dave Drachlis/Diocese of Alabama

[Episcopal News Service] The remains of the two most iconic symbols of Holy Trinity Cathedral in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, — its murals and its bells — are entombed today on the cathedral grounds awaiting resurrection.

Episcopalians have an opportunity on Jan. 12, the fourth anniversary of the earthquake that devastated wide swaths of the country, to hasten that resurrection. Already, there is new life in other parts of the diocese’s ministries.

Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori has called on the church to “pray and give” in a special offering that day to help the Diocese of Haiti rebuild Holy Trinity Cathedral.

Noting that cathedral housed 14 ground-breaking murals depicting Haitian religious life and the life of Christ in Haitian motifs that were regarded as a “national treasure,” Jefferts Schori said in her invitation that “rebuilding the cathedral offers hope not only to Episcopalians but to the nation as a whole – a sign that God is present, that God continues to create out of dust, and that God abides in the spirit of his people.”

The Episcopal Diocese of Haiti’s Holy Trinity Cathedral in downtown Port-au-Prince as it stood in October 2006, a little more than three years before it was destroyed by the magnitude-7 earthquake that struck at 4:53 p.m. local time on Jan. 12, 2010. The quake’s epicenter was 10 miles southwest of Port-au-Prince. Photo: Dave Drachlis/Diocese of Alabama

The magnitude-7 earthquake, whose epicenter was 10 miles southwest of Port-au-Prince, struck at 4:53 p.m. local time on Jan. 12, 2010, and was immediately followed by two aftershocks of 5.9 and 5.5 magnitude. Close to 300,000 people were killed. About a third of Haiti’s approximately 9 million people lived in Port-au-Prince at the time of the quake. Of those, 1.6 million people in the capital and elsewhere were left homeless on streets filled with the rubble of 80,000 destroyed buildings.

After Holy Trinity Cathedral shook and swayed and collapsed, three murals survived on three standing fragments of walls. The murals were later purposely reduced to pieces by Smithsonian-backed art conservators and stored in a container on the cathedral grounds as part of a hoped-for restoration in a new cathedral.

Fifteen bronze bells, known in carillon parlance as a “chime,” sounded from Holy Trinity’s tower from the time of their installation in the 1950s until Jan. 12, 2010. It is thought that 14 survived the quake. Two later went missing.

Elizabeth Lowell, the Episcopal Church’s director of development, was present on the cathedral grounds on a hot November day when diocesan chief operating officer Sikumbuzo Vundla and Haitian architect designer J-Hervé Sabin peeled back part of a cement vault’s corrugated tin covering to find just nine bells. However, the survivors each revealed a part of the story.

Sabin climbed into the vault and, with tracing paper and a pencil, gathered the name of each bell’s donor as well as the company that cast the bells.

John Taylor & Co., the British bell foundry that cast the cathedral’s bells, marked each of them with their name. The foundry has since supplied important information about each bell. Photo: Dave Drachlis/Diocese of Alabama

As roosters milled about and the Holy Trinity choir practiced “For Unto Us a Child is Born” in the background, Vundla searched the web via his iPad and discovered that John Taylor & Co., the company that cast the bells, is a British firm with an extensive archive of its work. Lowell said archivist George Dawson has since given her copies of the initial correspondence with then-diocesan Bishop Alfred Voegli about the bells (Voegli also commissioned the murals). Dawson also provided Lowell with the details of each bell’s diameter, weight, tone and cost.

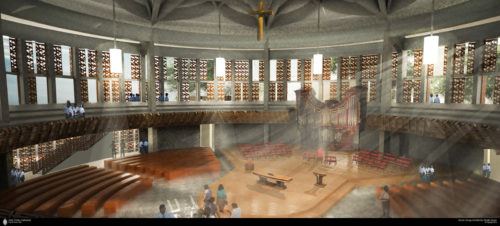

The plan for the new cathedral includes space for the bells. That plan was unveiled in October 2012. At the time it was estimated to cost $21 million to build the entire cathedral project – the so-called “Full Vision” – immediately and that price could increase to $25 million if it took three years to build, said architect Thomas Kerns of Kerns Group Architects, in Arlington, Virginia.

The project no doubt will be constructed in phases, Kerns told the church Executive Council during his October presentation, with the first being the main worship space which would cost $15 million, including a three-year cost-escalation estimate. Construction on the cathedral has not yet begun and worshippers continue to gather in covered, open-air church on the grounds.

Lowell, who with her colleagues is helping raise money for the project, agreed that rebuilding the cathedral “is going to be a very long-term piece,” noting that very few cathedrals, past or present, have been built in short periods of time.

Rebuilding Holy Trinity has been a priority for diocesan Bishop Jean Zaché Duracin since shortly after the devastating quake. He has predicted the new cathedral will be “the iconic symbol of the Episcopal Church in Haiti.”

More than 1,200 worshippers would sit in a circular fashion around and above a central altar platform, with the new altar positioned in the exact location of the previous altar of the previous cathedral. Artist rendering: Kerns Group Architects

Lowell said in a recent interview that “it’s the Haitians who are asking for this [new cathedral], and with good reason because to them it’s a national treasure and it’s a symbol of their faith.”

“This is food for the soul; this is food for their lives. It’s what they are asking for and it is what we could give them,” she said. “Arts feed the soul. This church feeds the soul. This cathedral is the center of the 254 schools and the two hospitals and the 13 clinics and everything else that we’re doing for the people of Haiti, without regard to their denomination.”

While the diocese lost 80 percent of its infrastructure, all of its schools have been open since April 2010, serving Haitians from kindergarten to university. Not all schools are up to their pre-quake complement of students and staff, and work remains.

In the Haitian capital, the quake destroyed the Holy Trinity primary, secondary, music and trade schools and the Convent of the Sisters of Saint Margaret (all on the cathedral complex), as well as St. Vincent’s School for the Handicapped, the Episcopal University of Haiti, College Saint Pierre (a secondary school) and income-producing rental properties.

There is a proposal to build an income-producing property in the Turgeau section of Port-au-Prince on land that once held the diocesan bishop’s house that was destroyed in the quake. The project would include office rental space, condominiums, apartments, a guesthouse with restaurant and a supermarket with a rooftop cafeteria catering to students at a nearby university.

The Holy Trinity primary, secondary and music schools are operating in makeshift conditions on the grounds of the cathedral with plans to rebuild. The music school has plans for an expanded school in Cange and a new school in Cap Haitien in the north, as well as a new facility near the Port-au-Prince campus itself.

The trade school has re-opened in a new, smaller facility in nearby Croix des Bouquets and now trains 600 students compared to the previous 1,700.

The diocese’s Faculté des Sciences Infirmières (http://www.fsil.org/), its nursing school, continues to train students in the country’s only four-year baccalaureate program. Photo: Laurie Lounsbury’s profile photo Laurie Lounsbury/Haiti Nursing Foundation

And all of the diocese’s churches and other institutions such as medical clinics are operating – albeit many in far less-than-ideal conditions. Still, there are bright spots and hope for the future. In Léogâne, the diocese’s Faculté des Sciences Infirmières, its nursing school, was relatively undamaged by the temblor and continues its four-year baccalaureate program (the only one in the country) for registered nurses. Twenty of its graduates are enrolled in a master’s level nurse practitioner program run in partnership with Hunter College in New York.

The Léogâne school will soon have a new neighbor in the form of an Episcopal University-approved four-year occupational and physical therapy training program. Those students will intern at St. Vincent’s School for the Handicapped.

St. Vincent’s was the first such school in Haiti when it was built in 1945 and is still the only place offering education for the blind in the country. Its prosthetics clinic has been rebuilt and some of the older deaf children are learning a trade there. Plans for rebuilding are coming together which call for an increased enrollment of 525 students (165 of them residential). St. Vincent’s is also home to Haiti’s only hand bell choir – all whose members are blind.

Outside Port-au-Prince, 33 of the diocese’s schools, rebuilt to international hurricane and earthquake resistant standards, were community shelters when Hurricane Sandy hit the island. Another 13 schools are being constructed now. Each school educates between 400 and 800 students.

Episcopal Relief & Development, which had a strong partnership with the Haitian diocese before the quake and has been involved in in post-quake work since, is part of an international effort to “green” some of the newly built Episcopal schools along with two public schools. That work includes equipping them with bio-digester sewage systems. The systems produce compost that is used in school gardens, hillside reforestation and the growing of fruit trees for transplantation near people’s homes. The methane produced by the systems fuels cooking stoves in the school’s kitchens. Another part of the effort involves collecting rainwater for use at hand washing stations and latrines.

Those involved in the schools effort, in addition to Episcopal Relief & Development, include the Presbyterian Church, which has had a long-standing relationship with the diocese-run nursing school and Holy Cross Hospital in Léogâne, and Scandinavian and German church-affiliated organizations, according to Lowell.

The latter group, she said, recognizes that the Episcopal Church “plays a huge role in education and so their way of helping is saying ‘we’ll build the building but, it’s your school, you run it.’”

An Episcopal Relief & Development report on its current work in Haiti is here.

It is such work that makes Lowell want to tell people that Haiti is “not all bleak and dark.”

She takes it as part of her job to “help change people’s mindset about Haiti … there are some really extraordinary things happening there.”

Lowell, who has traveled to Haiti many times since the earthquake, often in the company of other Episcopalians to whom she wants to tell the post-quake story, says the signs of hope in Haiti reach beyond the work of the Episcopal Church. They include such things as a concerted effort to pick up garbage in some parts of Port-au-Prince and the installation of solar-powered street lights. In Pétionville, what was once a 15,000-tent camp three blocks from the diocesan offices is now a well-used urban park and a soccer stadium that once housed 45,000 tents has been refurbished into a state-of-the-art soccer stadium. Six new governmental building are going up in the Haitian capital.

A child stands inside the Carra Deux Camp for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Photo: Logan Abassi/United Nations

Still, there is work to be done. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 172,000 people were living in 306 tent camps in September 2013 and faced deteriorating conditions. The office said in late 2013 that those numbers are down from a total of 1.5 million displaced in July 2010 and living in 1,555 camps. However, 600,000 Haitians faced severe food insecurity, and an additional 2.4 million lived in moderate food insecurity at the end of 2013.

The UN also said that there had been a 50 percent drop in the incidence of cholera since the 2010 outbreak that was later traced to UN peacekeepers. Still, the disease, once unknown in Haiti, persists and the UN humanitarian office predicts 45,000 new cases of the disease this year, acknowledging that the country still hosts half of the world’s suspected cholera cases.

The UN’s humanitarian plan for Haiti this year is here.

Meanwhile, Haiti vies for the world’s continued attention in the midst of several new and on-going humanitarian crises. UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Valerie Amos recently said that an unprecedented number of people are beginning 2014 either internally displaced or as refugees who have been driven from their homes by violence and bloodshed or uprooted by devastating natural disasters.

She said conflicts in Syria, the Central African Republic and South Sudan, as well as in the Philippines, which was devastated by typhoon Haiyan in 2013, , head the list. Amos noted crises in Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali and eight other countries in the band across the continent that marks the transition of Saharan to sub-Saharan Africa. And, she added, the UN is still concerned with on-going humanitarian issues in Afghanistan and Myanmar, as well as Haiti.

— The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is an editor/reporter for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu