Pauli Murray inspires new generation of ‘firebrand’ Black, queer Episcopal leadersPosted Dec 9, 2020 |

|

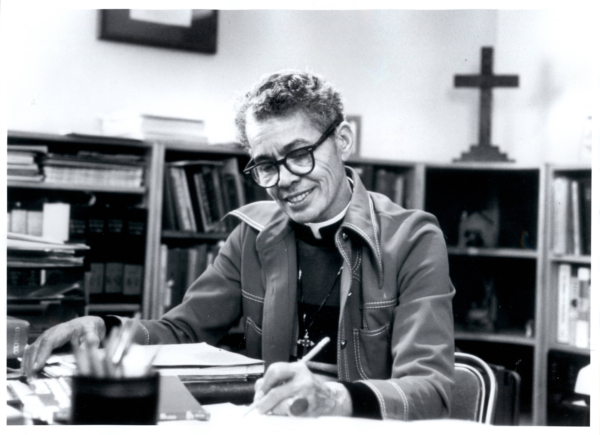

The Rev. Pauli Murray was the first Black woman ordained an Episcopal priest. Photo courtesy Carolina Digital Library and Archives/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

[Episcopal News Service] The Rev. Pauli Murray, a queer writer, lawyer and co-founder of the National Organization for Women who in 1977 became the first Black woman ordained an Episcopal priest, continues to inspire new generations of “firebrand” leaders to authenticity and activism.

These leaders include the Rt. Rev. Deon Johnson, who on Nov. 23, 2019, became the first openly gay Black man elected a bishop in The Episcopal Church. As the 11th diocesan bishop of Missouri, at 43, he is also the youngest person and the first immigrant from Barbados in The Episcopal Church House of Bishops.

Similarly, on Nov. 3, 2020, the Rev. Kim Jackson, 36, vicar of Atlanta’s Church of the Common Ground, a ministry to homeless people, was elected Georgia’s first out LGBTQ state senator with nearly 80% of the vote.

Celebrations commemorating Murray’s birthday on Nov. 20, 1910, were held across the church. Both Johnson and Jackson paid homage recently to Murray, who was born Anna Pauline Murray but took the name Pauli and struggled with her sexuality and gender identity. As First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s “firebrand” friend, Murray chronicled her human rights activism in her autobiography, “Song in a Weary Throat,” published after her 1985 death. Her childhood home in Durham, North Carolina, is now the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice and features “Pauli Talks,” a virtual series about current events through a Black and queer lens.

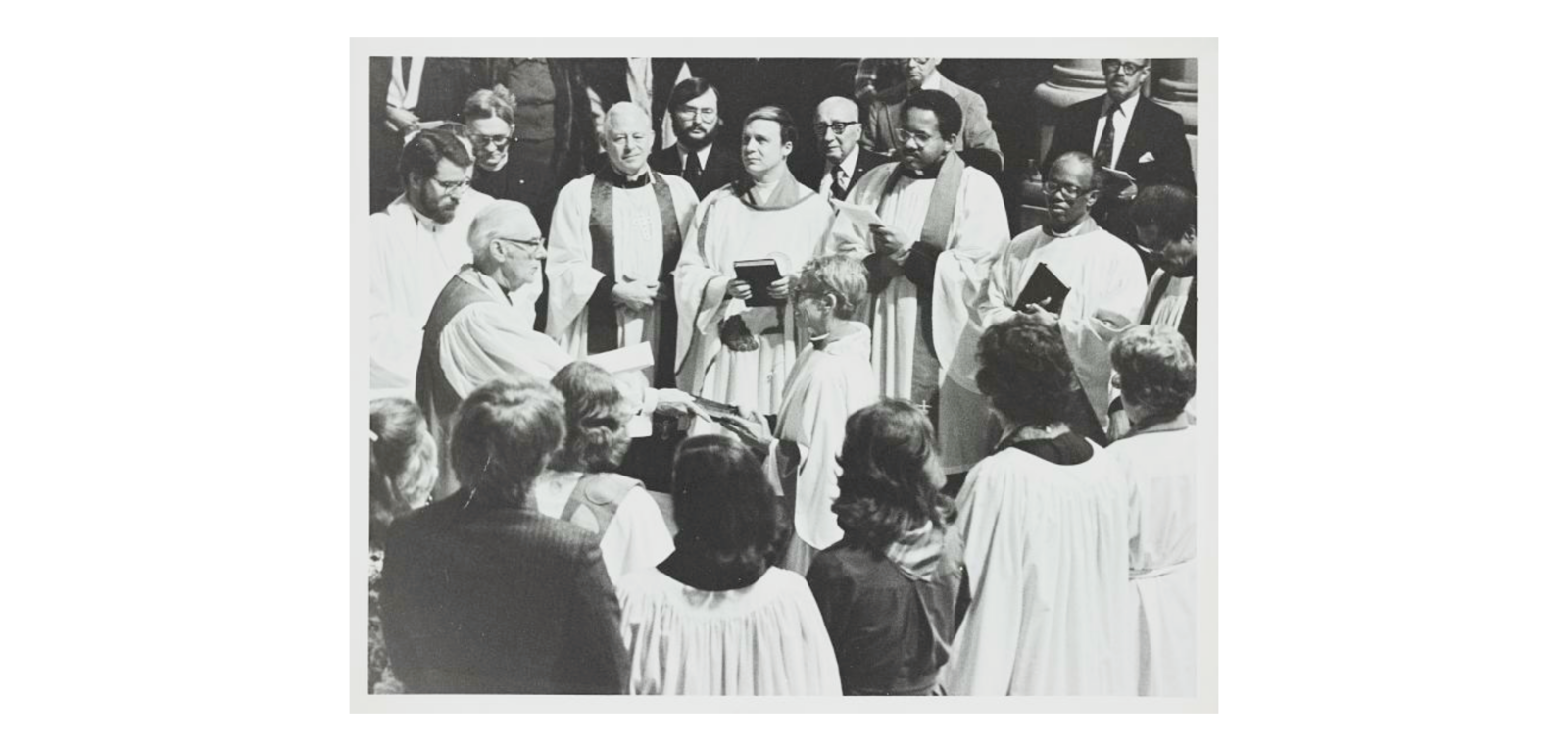

The Rev. Pauli Murray became the first African American woman ordained an Episcopal priest on Jan. 8, 1977, at Washington National Cathedral. Photo: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Milton Williams Archives

Center board member Jesse Huddleston, during a Dec. 1 “Pauli Talks” year-in-review webcast, noted that Murray continues to inspire hope that not only is “another world possible, but another world is happening. We’re living proof of that.”

Murray, who was added to The Episcopal Church’s calendar of saints in 2018, is a model for the inclusion of the gifts of those who are Black and queer, Huddleston said.

The Rev. Pauli Murray’s childhood home in Durham, North Carolina, is a center for dialogue, the arts, education and community activism for all people. Photo courtesy of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University

Designated a national historic landmark by the National Park Service in 2016, the center aims to reclaim Murray’s story, inspire a new generation of leaders, “and dismantle the discrimination she faced because of her race, gender, sexual orientation and gender identity,” according to director Barbara Lau. Only 2% of the 95,000 entries in the National Register of Historic Places focus on the experiences of African Americans, she said.

Currently, “there is a huge shift in public awareness around racial justice and racial reckoning,” Lau added. “When we look at the leadership of some of the most persistent movements aimed at that kind of justice, there’s young, Black, queer people in the lead. And there is less fear around claiming that identity.”

The Episcopal Church is planning to unveil a curriculum focused on Murray in January 2021. This lesson plan series will examine Murray’s complex story, which covers the gamut from faith to gender identity, and is geared toward middle schoolers, high schoolers and young adults.

Jackson, the Georgia state senator-elect, “identifies boldly as Black and queer,” a way of rejecting the kind of past shame that Murray and others have endured because of their gender identity, she said.

“We will not be ashamed of what we look like and who we love and who we’re attracted to,” she told ENS recently. “Being Black and queer, that’s me. It’s different, but it’s not bad.”

After joining The Episcopal Church as a seminarian more than a decade ago, Jackson discovered Murray, who resembled “people who looked like me and loved like me. This genderqueer woman, who was Black, who was politically engaged, who was also a priest – she modeled for me what I hope to achieve in my own life.”

Jackson, a native of South Carolina and a former Baptist, said her call to ordained ministry began at about age 8. Political aspirations followed five years later when she realized that both were ways to effect positive change.

Jackson explained that she dreams of a new kind of future for the homeless community she pastors, where barriers across class and race will crumble. Yet fear and the desire to return to normalcy could thwart the racial reckoning occurring within the culture and the church, she said.

“The work of transforming how we address the issues of white supremacy, that’s not normal,” Jackson said. “The work of trying to bring racial justice to our nation and to our church, that’s not normal.”

“Anti-Blackness is a disease that plagues our world,” she added. “As we are doing this work of trying to bring healing, we have to include racial reconciliation, racial justice, racial transformation. It is as essential to our well-being as it is to stamp out COVID-19.”

The pandemic and the virtual worship it has spawned have reduced geographic and class barriers to traditional church attendance, she said. “People who have to work on Sunday mornings because they have jobs that require that of them are now able to engage worship at a different time. I hope we will continue to build relationships with people beyond the walls of churches.”

The future church she hopes for also will be sensitive to language. “It matters to people when they hear me say, ‘siblings in Christ, we welcome you.’ It might not matter to the cis straight white guy who never heard of those terms. But for the nonconforming person, that matters, and it helps move us closer once again to the kingdom and the ‘kin-dom’ of God.” A cisgender straight person identifies with the gender assigned at birth and is attracted to members of the opposite sex.

For Johnson, who was consecrated bishop in June, the pandemic has been a time “to dream of the church that I’ve always wanted the church to be.”

From Murray, he learned “to be who I am.” Initially that meant, in spite of sensing a call to ordained ministry at age 11, he didn’t think he would become a priest, much less a bishop, “because the church hasn’t always dealt too well with gay people.”

While serving as a priest in Michigan, Johnson created a safe space for LGBTQ teenagers. His church created a Friday night “speakeasy” and transformed the church hall to host alternate proms “so the LGBTQ teenagers could dance with the person they wanted to dance with and hold hands with the person they wanted to hold hands with,” he said.

Now, as bishop to a diocese of about 11,000 Episcopalians in the central and eastern half of Missouri, including the city of Ferguson, Johnson emphasizes racial reckoning as a priority. On Aug. 9, 2014, Michael Brown Jr., an unarmed 18-year-old Black man, was fatally shot by a white police officer, sparking national attention and months of racial unrest in Ferguson.

“As a church, we have come to a place where we are now invited to actually live out what we say we’re about,” Johnson said. “If the election a while ago taught us nothing, it should teach us as a church that we need to be about the business of reconciling God and God’s people.

“The church is made for this moment. The church must be bold in this moment. This is what God called us into being for, to bring people together under a common goal. Like the presiding bishop says, love needs to be the way.”

Although he represents multiple identities and numerous “firsts,” he says emphatically, “at the end of the day, I am called to serve the people of the Diocese of Missouri, and that’s what I’m going to do.”

For example, age makes Johnson “not a millennial, not a Gen Xer. I’m in that weird class called ‘Xennials,’” he says laughingly, which means “I grew up without technology but embraced it early on.”

His life experience has forced him to navigate the world differently. “If we are talking about racism, I know what that feels like,” he said. “If we are talking about homophobia, I know what that feels like. If we are talking about xenophobia and keeping immigrants out, I know what that feels like. For me, this is not something I hear about, or something that we write a paper and talk about it; it is something I have to live every day.”

Consequently, the theme for the diocese’s Nov. 19-21 convention was “Dreaming, Daring, Doing Together in Christ,” and also represents the moment the church was made for, he said. “Forget surviving. I want folks to thrive.”

Not having all the answers is OK, Johnson added, “because that’s all the messiness of being God’s dream.”

– The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a correspondent for Episcopal News Service based in Los Angeles, California.

Social Menu