Christian groups decry U.S. policy change on Salvadorans as Episcopalians offer supportPosted Jan 11, 2018 |

|

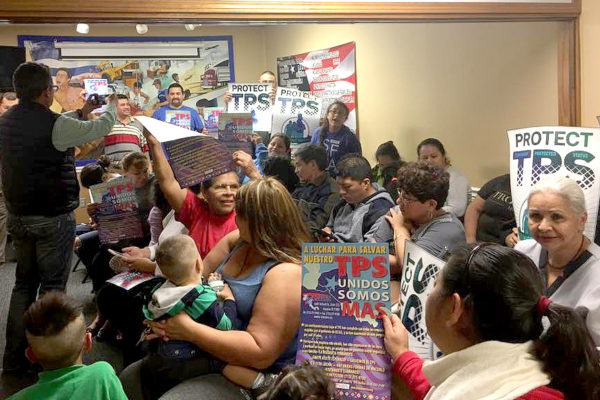

Dozens of people attend an event this week organized by Crecen in Houston to provide information and show support for those affected by the Trump administration’s decision to end Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, for Salvadorans. Photo: Crecen, via Facebook

[Episcopal News Service] The Episcopal Church and ecumenical partner organizations are calling on Congress to act if the Trump administration refuses to reconsider its decision to end immigration protections for nearly 200,000 Salvadorans who have for years been allowed to establish roots and raise families in American communities.

At issue is the policy known as Temporary Protected Status, or TPS. The Trump administration has taken a hard line on the policy, saying it never was intended to offer immigrants permanent residency. The status typically is granted to foreign nationals from countries suffering from natural disasters or wars.

In November, the administration ordered an end to TPS for more than 50,000 Haitians by mid-2019. President Barack Obama had approved that TPS designation after a 2010 earthquake devastated Haiti.

Salvadorans have made up the largest group allowed to remain in the United States under TPS. The protection from deportation was granted to Salvadorans by President George W. Bush in 2001 after an earthquake struck El Salvador. Now, Salvadorans will have until September 2019 to obtain legal permanent residency in the United States or leave the country.

“If there’s any group of people you can imagine wide agreement that they not be deported, it’s this set of people,” said Sarah Lawton, a lay leader in the Episcopal Diocese of California who has made outreach to Salvadorans “an issue of the heart for me” since the 1980s.

The Salvadoran families who are being assisted by religious groups in San Francisco are contributing members of the local community, said Lawton, a member of St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church. The families typically include hard-working parents and children who are U.S. citizens because they were born here. For such families, the news on Jan. 8 was devastating.

“I woke up on Monday morning to a call from a friend who is terrified she’s going to be deported,” Lawton said.

Her friend is a Salvadoran with TPS whose husband is from Honduras and faces his own uncertainty because the Trump administration is ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, that has allowed him to remain in the U.S. Their two children are both citizens.

The Episcopal Church regularly advocates for maintaining TPS, particularly when forcing some people to go back to their birth countries could break up families, pose threats to safety or both. General Convention approved a resolution in 2015 pledging to support Temporary Protected Status “for all immigrants fleeing for refuge from violence, environmental disaster, economic devastation, or cultural abuse or other forms of abuse.”

The church’s Office of Government Relations raised concerns about the change in policy toward Salvadorans.

“Multiple studies have demonstrated that El Salvador cannot safely repatriate nearly 200,000 individuals,” the Office of Government Relations said in a Jan. 8 statement. “El Salvador is ranked the most violent country in the Western Hemisphere and has suffered from continued natural disasters, stagnant economic growth, and a lack of infrastructure and health systems. Further, the majority of Salvadoran TPS holders are economic, cultural and social contributors to the U.S.

“Congress and the administration must devise a long-term solution for Salvadorans and others currently holding TPS that recognizes both the realities of the country’s harsh conditions and humanely addresses the realities of the individuals impacted.”

The Department of Homeland Security, in announcing the decision to end TPS for Salvadorans, said it is up to Congress to decide whether to grant long-term protections for those affected. It justified an end to temporary protections by citing the success of earthquake recovery efforts.

“Based on careful consideration of available information … the Secretary determined that the original conditions caused by the 2001 earthquakes no longer exist,” Homeland Security said in its Jan. 8 statement.

But President Donald Trump’s own State Department has acknowledged the dangers of life in El Salvador. In a travel warning issued February 2017, the State Department advised U.S. citizens “to carefully consider the risks of travel to El Salvador due to the high rates of crime and violence.” It noted the country’s homicide rate is among the highest in the world, and gang activity is “widespread.”

The Trump administration previously announced it was ending Temporary Protected Status for citizens of Sudan and Nicaragua, in addition to Haiti. For now, it remains in effect for citizens from Honduras, Nepal, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen, though the administration is due to review each designation in the next year or so to determine whether to extend or terminate those protections too. The decision on Syrians is due later this month.

Anglican bishops in Central America have scheduled a meeting this month to discuss the impact of migration and repatriation in the region, including as a result of changes in American policy. The bishops will, in part, respond to “the lack of preparation to face the social effects of the migration policies of the United States government,” the Anglican Church of Mexico said.

Christian groups and denominations have joined the Episcopal Church in objecting to the elimination of TPS. A representative of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a statement calling the Trump administration’s decision “heartbreaking.” Church World Service also put out a statement denouncing the decision.

Cristosal, an El Salvador-based human rights organization with roots in the Episcopal and Anglican churches, released a statement warning that the end of TPS will cause “unnecessary human suffering,” not just for the Salvadorans ordered to return to their native country but also for their estimated 190,000 U.S.-born children and “the many U.S. communities that depend on and benefit from migrants’ economic, cultural and social contributions.”

Elmer Romero, an Episcopalian in Houston who serves on the Cristosal board, attended a meeting on TPS held by the support group Crecen this week. The 60 to 80 Salvadorans who attended were asked how many planned to voluntarily move back to El Salvador: “No one raised their hands,” Romero told Episcopal News Service.

“There is not any type of economic development to create opportunities, especially for the youth population,” Romero said of El Salvador, and cartel- and drug-related violence is an ever-present danger.

He also disputed the Trump administration’s claim that the country, outside of its capital, has recovered from the earthquake. “If you go deep in the society, there’s still families who basically lost everything. They continue facing a lot of challenge.”

Romero, a Salvadoran-American who moved to the United States in 2000 before the earthquake, works as a program manager at Houston Center for Literacy and has been active for the past 17 years in helping immigrants and refugees find services in this country. His wife is an Episcopal priest.

He wasn’t surprised by the Trump administration decision this week, and he called it a success that Salvadorans were given 18 months before TPS expires. He is hopeful that advocates can persuade Congress to pass legislation providing permanent protection for the residents he serves. Until then, he said, they face an uncertain future, and some are considering arrangements that will allow their children to remain in the United States.

Similar arrangements are being discussed in the San Francisco area, according to Lawton, who works as a program coordinator at the Center for Labor Research and Education at the University of California-Berkeley.

Lawton said her church, the Diocese of California and other advocates for immigrant communities are helping to connect Salvadorans with legal representation to fight deportation and rallying for legislative solutions in the state capital and in Washington, D.C.

“We’re a sanctuary diocese. We’re a sanctuary parish. We’re doing everything we can to ensure due process for the people coming through the process,” Lawton said. “Together we lift up our voices.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu