One disaster after another: Coping with compassion fatigue can be a challengePosted Dec 21, 2017 |

|

A woman breaks down and cries in the rubble of her burned-out home after a wildfire in California destroyed it. Photo: Reuters/John Gress

[Episcopal News Service] People would be forgiven if the running list of natural disasters around seemed to pile up in 2017, especially in the months since May.

There is such a thing as compassion fatigue. While the first studies centered on individual professional caregivers and how they lose the sense of caring that once inspired them, there is also an understanding that organizations and even society as a whole can suffer from what some call “empathy fatigue.”

Studies show that public empathy does wane within a few weeks of a disaster, but what happens if the disasters keep coming?

Diocese of Fond du Lac Bishop Matt Gunter in late October summed up his feelings. “I’m tired. My heart hurts. My soul is weary,” he wrote in a blog post titled “Loving Your Neighbor in an Age of Compassion Fatigue.”

The post “seems to have struck a nerve,” Gunter told Episcopal News Service during a Dec. 20 interview. “It skyrocketed to the top of my all-time clicks almost immediately, so that suggests something,” he added.

The world has contended with a lot of hurt this year. First it was torrential rains and flooding in Sri Lanka in May that killed at least 224 people. Then it was the series of hurricanes – Harvey, Irma and Maria – that tore through the eastern Caribbean and deluged Texas with historic amounts of rain from August into early October. The storms killed as many at 800 people, although the death toll is controversial because of accusations of manipulation of the process of attributing fatalities to the storm. Property loss estimates range close to $350 billion.

In the midst of those storms, two major earthquakes struck central Mexico in September, killing 470 people, displacing thousands and causing an estimated $2 billion in property damage.

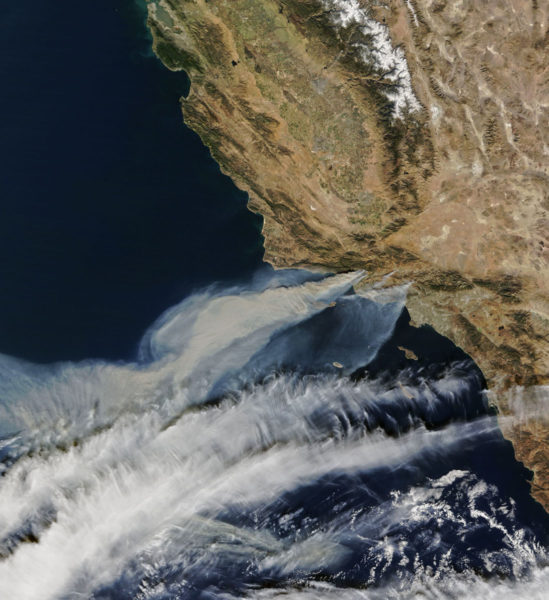

Satellite image from Dec. 5 shows smoke from Thomas, Rye and Creek Fires in Southern California. Photo: NASA Earth Observatory

Then, Northern California erupted in fast-moving and devastating wildfires in mid-October. Some 44 people died, and property insurance claims have topped $9.4 billion. And Southern Californians are still battling the remnants of fires that swept through the greater Los Angeles area beginning on Dec. 4. One person has died, and estimates of property damage are still being calculated. The costs of the U.S. disasters have a ripple effect, with affected municipalities anticipating revenue shortfalls both because of the cost of fighting the fire and because they will not be able to collect taxes on destroyed properties.

Add to the mix the human-caused disasters: mass shootings at a concert in Las Vegas and a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas; deadly riots in Charlottesville, Virginia; and terror attacks in Manhattan. Remember that five years ago, it was Newtown Elementary School, and people thought things would surely change after children were gunned down in their classrooms. Thus far this year, there have been 413 mass shootings in which four or more people were shot in the United States, according to statistics kept by Mass Shooting Tracker, a crowd-sourced database of U.S. mass shootings.

News of environmental disasters and sectarian violence across the world, coupled with partisan divisions fought across media platforms in the United States and elsewhere, add to what psychologist Jamil Zaki has called a “habituation [that], paired with a feeling of numbness, can drain our empathy, motivating us to stop caring about victims of tragedies.”

“Cynically throwing our hands up at the surreal death tolls of natural disasters or massacres and changing the channel can be self-protective, ‘costing less’ psychologically than vicariously experiencing the suffering of strangers,” he wrote in 2011, the year Twitter came online. The years since have seen an explosion of news, graphic images and videos, and opinions flooding into people’s brains and hearts.

“Communicating the suffering of others does not always stir empathy, and can even be counterproductive, for example when an inundation of suffering depicted in stories and pictures leaves people feeling helpless or exhausted,” Zaki said.

Fond du Lac’s Gunter told ENS that he is “just not sure we’re wired to absorb it.” There was a time when people lived fairly isolated lives, knowing about what he called the “normal human heartaches” of people in their communities, things like house fires and heart attacks and people dying far too early. Perhaps they got news of earthquake and other kinds of faraway destruction. But now, when “you turn on the TV, you’re faced with trains wreck and fire and images of war and hunger.”

That instantaneous news raises the question of “how do we manage the input from all the 24/7 news,” Gunter said. “And you add on to that the 24/7 political commentary, which is mostly geared to agitating you in the first place. We’re all on edge because here are people making money and gaining power and influence by keeping us agitated. That’s a whole other sermon, but it is a place where I think the church has something to say.”

In his blog, he suggested that many people have experienced the symptoms of compassion fatigue: disturbed sleep; unwelcome involuntary thoughts, images or unpleasant ideas; irritability, impatience or outbursts of anger; hypervigilance “and a desire to avoid people who we know are hurting or who you know will disturb your equilibrium.”

Outsized anxiety and fear can develop. Gunter told ENS that in the past weeks, at least two priests have told him that their congregations are calling for armed guards in church. He has cautioned people to realize that the Texas church shooting was a domestic dispute that played out in a locale that could just as easily have been a post office or a store.

All of these pressures, he wrote in his blog, can lead to a “psychic numbness” that makes people want to hunker down and give up trying to live with compassion for neighbors.

“And yet, as Christians, we must resist this tendency even as we acknowledge its reality and power. In his summary of the Law, Jesus enjoins us to, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ That is a call to compassion, a call to care,” Gunter wrote.

The question, he told ENS, is “how do we break through the fear and anxiety that in many is not rational; it is emotive.” And, Gunter added, given the polarization in society, “people are pretty quick to say you’re being liberal or something else and they can write you off because you are not giving them what they want.”

The good news of the gospel needs to be preached and lived “in a way that can be actually be heard” above all the din.

The call to do that and to remain compassionate is not always easy to answer, and answering it can lead to the very fatigue that many people are experiencing. The bishop offered some steps for finding balance:

- Make time each day to pray, and not just alone, but with others.

- Find someone to talk to who will encourage you rather than reinforce the things that agitate you.

- Set aside Sabbath time to “rest from the worries of the world” (including avoiding the news and the internet) and do something restorative.

- Acknowledge human vulnerability and dependence on God.

- Do what you can and trust the rest to God, focusing on self-care and taking on only what you can manage.

- Dwell on the positive, not the negative.

- End each day by naming the good and thanking God for at least three things.

Gunter elaborates on these practices in his blog post.

Many people have told Gunter that they are trying to take on that last discipline of thankfulness. His understanding of psychology says that “just that simple practice can reorient your perspective in ways that are measurable.”

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is interim managing editor of the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu