Virginia congregation honors slaves who built church, offers ‘gratitude and repentance’Posted Feb 17, 2017 |

|

Nikki Henderson, left, and Edwin Henderson, center, listen as the Rev. John Ohmer speaks at the dedication Feb. 11 of a plaque honoring the slaves who built the Falls Church, in Falls Church, Virginia. Photo: The Falls Church, via Facebook.

[Episcopal News Service] If an appreciation for history warms your heart along with the Holy Spirit on Sunday morning, there are a few things to know before worshiping at the Falls Church.

First of all, there are two Falls Churches. The city of Falls Church, Virginia, was incorporated after the Episcopal church that gave it the name. The congregation predates the Revolutionary War and worships in a church built in 1769. It was designed by James Wren, an architect whose name can be found on a plaque embedded in the brick walkway leading up to the church door.

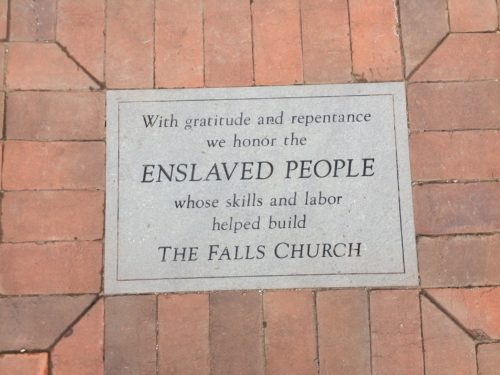

And, the church was built by skilled but enslaved laborers – a longtime omission in the church’s history that recently was corrected with a second plaque honoring those slaves and offering “gratitude and repentance.”

The brick walkway now features parallel plaques to architect James Wren and the slaves who built the church he designed. Photo: Falls Church, via Facebook

“It was an opportunity to say more than to just acknowledge,” said Nikki Henderson, one of the leaders of the effort to identify slaves’ role in the church’s early years. “It was an opportunity to say something about the institution that put them in the position to be forced laborers.”

It also follows broader efforts by the Episcopal Church to emphasize racial reconciliation and come to grips with the church’s past complicity in slavery and racism.

Bishops and deputies began discussing racism as early as the 1976 meeting of General Convention. A resolution approved at the 1991 General Convention committed the church to “addressing institutional racism inside our Church and in society,” and a 2000 resolution renewing that commitment for another nine years lamented “the historic silence and complicity of our church in the sin of racism.” The issue of racism has been discussed at every subsequent General Convention.

The Falls Church was eager to end “the historic silence.”

“Racial reconciliation is a huge part of living out our baptismal covenant, and that’s what drives so much of our identity here,” said the Rev. John Ohmer, rector of the church.

He said the congregation and community have enthusiastically supported efforts “not to run from our history but to own that part of our history that was slaveholding, and then to own the fact that racism in our country – systemic racism, church racism, individual racism are still very much with us.”

Henderson and a team of volunteer researchers at the church spent several years trying to bring the slaves who build the church out of anonymity. There were no clear-cut records attributing the church construction to slave labor, but the researchers found enough evidence to reach that conclusion with confidence.

“It’s right up under the surface, and like many historical facts during that time, because of the sensitivity of it, you’re not going to find a document that says (it), so you have to take an educated guess,” she said.

The project stemmed from Henderson’s conversation years ago with a woman at the church who had some initial information that pointed to the true story of the building. With the help of a church archivist and the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, which Henderson and her husband lead, more documentation began painting a clearer picture.

A labor shortage was one key detail. Just as free and enslaved Africans built the White House later in the 18th century because other workers couldn’t be found to do the job, Henderson’s team discovered that Wren was unable to recruit men to build the new Falls Church despite advertising in a local newspaper.

He eventually decided to build it himself, Henderson said. Such a project would be too much for one man to accomplish.

The church researchers also found Wren’s will, which revealed he had 23 slaves who were given to his wife after he died. One was identified by name, Charles, and said to be a skilled laborer. Furthermore, slaves at that time were known for their brick-making skills, another detail supporting the conclusion of the researchers.

Now the contributions of those enslaved laborers are being fully acknowledged. The new plaque was dedicated in a ceremony Feb. 11, and it rests right alongside the plaque honoring Wren.

Falls Church deliberately chose the word “repentance” over “apology” in crafting the plaque honoring the enslaved laborers who built the church. Photo: Falls Church, via Facebook.

“With gratitude and repentance we honor the enslaved people whose skills and labor helped build the Falls Church,” the new plaque reads.

Ohmer emphasizes “repentance,” saying church members felt “apology” would not have been a strong enough word. That quest for repentance is one that has been adopted by the Diocese of Virginia in its racial reconciliation efforts.

“By expressing repentance and by naming with gratitude ‘the enslaved people’ who helped build their church, the clergy and parishioners of The Falls Church have not only corrected an error of omission, they have committed themselves to further acts of reconciliation,” said Aisha Huertas, the diocese’s intercultural ministries officer. “As a diocese and as a community of faith, that’s precisely what all of us are called to do, both within our own walls and in the broader community.”

The experience has strengthened Henderson’s appreciation for Falls Church Episcopal.

“It’s a wonderful congregation,” she said, adding, “I am African American and the church is predominantly white, and I feel strongly that part of our racial divide is because we don’t know each other.”

Henderson, 68, joined the church a few years ago partly out of her interest in bridging that divide, with a nod to Martin Luther King Jr.’s observation that 11 a.m. Sunday is America’s most segregated hour.

“We’ve talked about healing the racial divide,” Henderson said. “I think we need to broaden that range.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu