South Dakota program restores the ‘shared roots’ of disappearing prairie grassesPosted Jan 5, 2023 |

|

Deanna Stands scatters seeds at the Bishop Hare Center in Mission, South Dakota. Photo source: Lauren Stanley

[Diocese of South Dakota] Nestled under the accumulating snow from a mid-December South Dakota blizzard, prairie grass seeds and wildflower seeds bide their time, waiting for the right moment — perhaps this spring and summer, perhaps next — to burst forth.

“These plants have crazy long root systems,” according to Mia Werger, who works for the Ecdysis Foundation in Brookings, South Dakota, and whose senior thesis at Augustana University focused on restoring the prairie. “The root system does 90% of the work, because the roots are 10, 12, 15 feet beneath your feet.”

Before growing into the prairie grasses and wildflowers, the seeds actually wait for the right moment, Werger explains, depending on whether there is enough water in the soil to enable the plants to grow and thrive. Sometimes, she says, it can take two years before they burst forth.

The grasses pull carbon from the air through their deep roots and store it back into the earth, creating what is called a carbon sink. “If carbon is in the earth,” she says, “it’s not in the air, which keeps temperatures down. Restoring the prairie keeps the soul alive — it lets in air and water and insects and microorganisms,” she says. “We need these plants to renew the earth. Deeper roots equals … healthy soil.”

Werger has been helping the Diocese of South Dakota with its “Common Ground, Shared Roots” initiative, a program that invites the people of South Dakota to plant a mix of prairie grasses and wildflowers everywhere they can.

“One thing that we believe is of concern to all in South Dakota is the importance of our land, our reliance upon it and the necessity for us to take care of it as God’s gift to us and to all of creation,” says the Rt. Rev. Jonathan Folts, bishop of South Dakota.

“Common Ground, Shared Roots” came about as part of the Diocesan Leadership Initiative, a program of the Episcopal Church Foundation. Folts, along with canon for finance and property Mitchell Honan and Diocesan Council members Warren Hawk and Stephanie Bolman-Altamirano, met with a coach, Pastor Brian Brown, and came up with the idea for the program.

Three pilot projects were created at the Bishop Hare Center in Mission, on the Rosebud Reservation with the Rosebud Episcopal Mission; at St. James, Enemy Swim, on the Lake Traverse Reservation with the Sisseton Episcopal Mission; and at St. John’s, Eagle Butte, on the Cheyenne River Reservation, with the Cheyenne River Episcopal Mission. In each place, a small plot of land was set aside and prepared, and then seeded with the prairie grasses and wildflowers.

Cindy Rains of St. Andrew’s, Rapid City, plants seeds at the Bishop Hare Center on the Rosebud Reservation. Photo: Lauren Stanley

“I’m very grateful to the members of our team who chose to accept the invitation to invest their faith, time, and energy into this project,” says Folts. “And I am also very grateful to those who hosted these three events. We are all about ‘risking something big, for something good,’ as William Sloane Coffin states in his benediction. And this was a risk that we all felt was very important to take.”

In her presentations, Werger emphasizes that the deep root system of the prairie grasses is what will make this program successful.

“A lot of what makes these plants so important is the root system,” she says. “It stays there year after year, and keeps getting bigger. It’s a living ecosystem underground pulling away carbon and storing water.

“The potential of grasslands to store carbon is incredible,” she says, “and it doesn’t get a lot of attention, but it is an important part of the climate change discussion.”

Lawn grass, the kind grown in most urban settings, “does pull in carbon,” she explains, “but some of the ways that we treat plants now, we manage them so poorly that they become a source of carbon instead of a sink. Look at how much energy goes into maintaining those lawns: cutting the grass with gas-powered machines, using fertilizers and weed killers.”

Grasses found in typical lawns aren’t as effective, because the roots are so short. Hawk, who is also a member of the Standing Rock Tribal Council, talked about how his work for the tribe focusing on renewable energy made this environmental program so appealing.

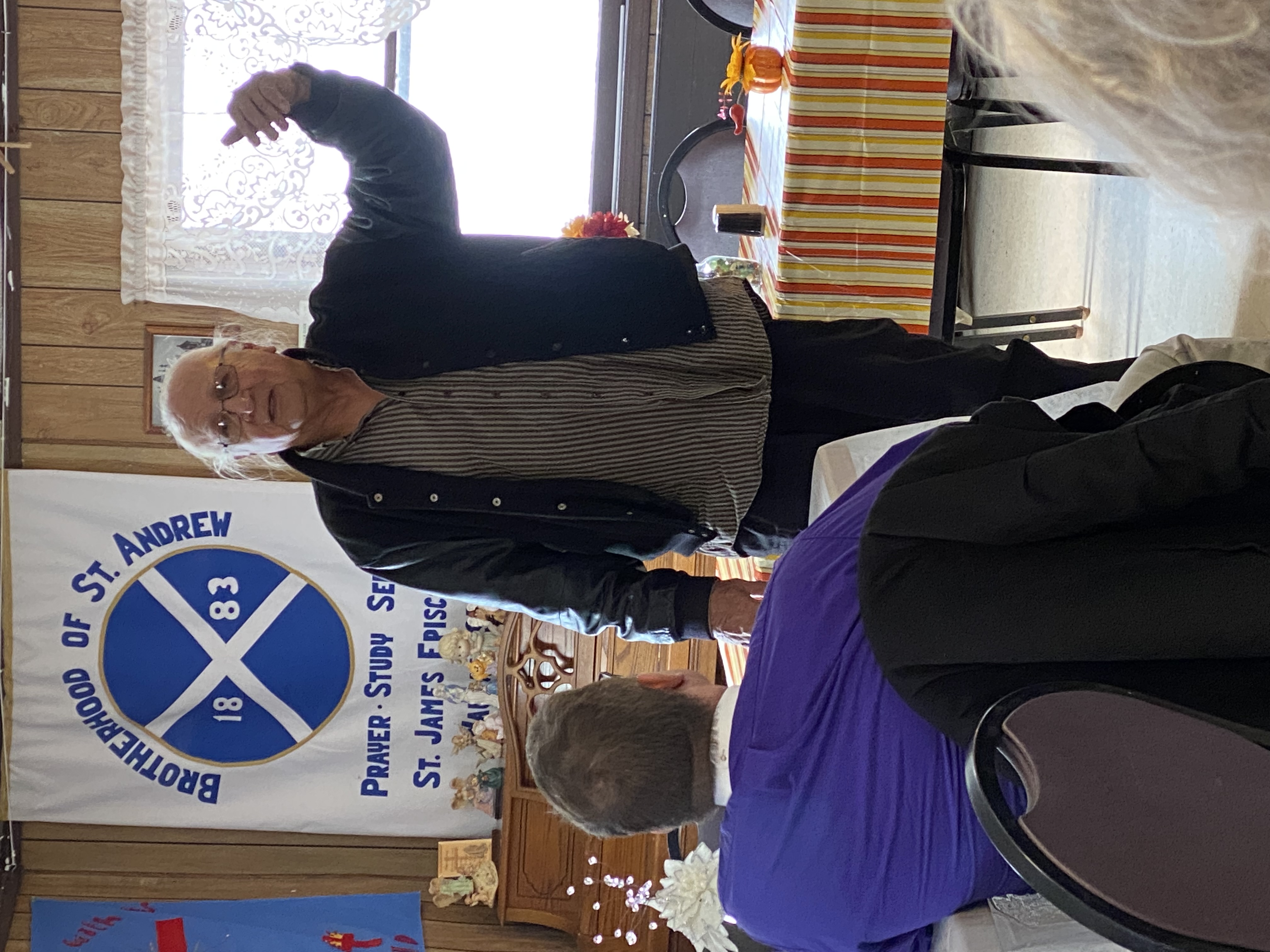

Mia Werger of the Ecdysis Foundation in Brookings talks about prairie grasses. Photo: Lauren Stanley

“I was listening to the group talk, and they were talking about what kind of project, and we were … discussing how far apart we are (geographically),” Hawk says. “We wanted to devise a project that would bring people together. Bishop said what he thought was a common thing for us was the land itself. We had talked about the pioneer history, the Native American history, and (Bishop) came up with, ‘Well, what can we do about the land?’

“Mitch was the one who came up with the idea about planting wild grasses,” Hawk says. “We started talking about it, so that’s how it formed. I thought it was a really cool idea, so we named it ‘Common Ground’ because that’s what we can all relate to, the land.”

Honan, who cares deeply about our environment, says, “We cannot afford to ignore climate change. … The issue is so daunting that individuals quite reasonably feel that they cannot do anything meaningful.

“I feel called by God to be part of the solution, and to bring love and hope into people’s lives,” Honan says. “Most days, I don’t get a chance to do that very directly. With ‘Common Ground, Shared Roots,’ though, I saw people come together and do life-giving and easily replicable work together, while also discussing some of the cultural and environmental challenges that we face.

“What I love about this project,” he adds, “is that it offers anyone who owns even a small amount of land in the Midwest an opportunity to do something that actually takes carbon out of the air and puts it back in the ground. The benefits of restoring wild grassland plant species go beyond carbon sequestration, too. These kinds of grasses are more resilient to both drought and flood, and provide food for birds and insects.

“This project,” he says, “is all about bringing people together on this land that we occupy together, and in so doing, healing pieces of land and thereby ourselves. … ‘Common Ground, Shared Roots’ invites all Episcopalians in our diocese and beyond to dream bigger. By simply following a few steps, and then planting certain seeds, even a small plot of land can become a sink that literally reverses climate change, while also giving animals habitat and food, and keeping more rainwater in the ground for the driest months of the year.”

Werger developed the initial program on which “Common Ground, Shared Roots” is based, Honan says. The diocesan team expanded her program and changed it so that it is now “a model for connecting across cultures on the common ground.”

An important component of the initiative is learning about the land itself and its history. “Bringing everyone together into one area to talk about the land and what it meant to Native people (is) where the idea of story-telling came in,” Hawk says. “Then Mitch knew about (Werger), who could talk about the grasslands. It’s called regenerative agriculture — restoring the lands back and bringing back the former grasses that used to grow on the prairie. … We really didn’t know what to expect until the first meeting. When we did the first presentation on the Rosebud, it all seemed to work out.”

Hawk says that what was amazing to him was “the way the biologists were talking about planting these seeds that would eventually help restore what would commonly have grown in this area back in the 1600s, 1700s, 1800s, before agriculture took over the land. They talked about these seeds like they had their own spirit, their own identity.”

That description, he says, is “how Native people talk about how we are all related, and we refer to plants and animals like they are part of us.”

In each of the presentations at the three pilot sites, Hawk says, the biology presenters said that “when we plant these seeds, they won’t come right away. They will sit in the ground, monitor the environment — they (sometimes) will sit for a couple of winters, measure the snowfall, process the weather and how much water they get … and once they get a feel for what the environment will do … they will reveal themselves then. They will have adapted themselves to the environment so they will survive, basically.”

Hawk compares that concept to how people live. “Isn’t that what we do as people, when we move from one area to another — we get a feel for what’s going on around us, and then get involved? (The presenters) talked about the seeds like they are living human beings, with a brain.”

The Rev. John D. Willard V, superintending presbyter of the Rosebud Episcopal Mission West, hosted the first presentation at the first pilot site, on the Rosebud Reservation in September. The idea of restoring the prairie appealed to his environmental background and his own experience from his home in Virginia, where he lived before coming to South Dakota.

“I had a big swath, a quarter-mile-long one, that I did for butterflies. So when Mitch (Honan) was saying, ‘Let’s get this back to grasslands,’ I thought that was really cool,” Willard says, “because you reestablish the flora and you get little bugs and other things you cannot see, and it’s natural. Get back to the natural stuff. … It really improves the land in all sorts of ways, and helps improve the water quality and the land.

“I hope we can get a nice little strip going at the Bishop Hare Center and then extend it,” Willard adds. “I would like to see what all the little bugs are, so we can get new bugs, new birds, new predatory animals.”

Dakota elder John Eagle talked about the history of the land and the people in Sisseton. Photo: Robin Bowen

The idea of learning the history of the land appealed to Willard because of his work before becoming a priest. Learning the historical context helped with work projects for that job.

“To have the story of how this land has changed over the years, and what it means, and where we can put it back to, and what that means, is an important part of the story,” he says. “What is the best use of this land? Perhaps it should be restored to what it once was. Perhaps it could be restored to land for the buffalo.”

Willard also trained and worked as an oral historian, “so how we construct our past and our history is important to who we are as a people. Sharing the stories,” he says, “reinforces our sense of community, our sense of identity, our connection with our environment.”

Cindy Rains, a member of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Rapid City, attended that first presentation at the Bishop Hare Center. “I’ve been [participating] with environmental and creation justice ministries, and doing quite a bit of that,” she says. “I’m excited about the possibilities of planting native grasses and native plants.”

Rains says she would like to plant prairie grasses in her entire front yard, but, she says, “it’s kind of like the one fish going against the 500 coming the other way. It’s an upward battle in environmentalism.”

She says that the presentation was “exciting because there are people interested [in this project] like me. The young people from the Ecdysis Foundation were impressive.

“I was surprised to see that the diocese presented something that’s quite impressive and thought, ‘Wow, this is cool. This is really cool!’ I would love to be part of the project. I have a boulevard that … I would like to transform into natural habitat. I am going to do this! I’m excited!”

Sandy Kaitfors, another member of St. Andrew’s, Rapid City, also attended the first presentation and was impressed by the presenters, especially Werger. “Seeing what we did as far as common grounds go, and seeing how the ground was prepared for us, and the lesson from the young people, it was all incredible,” she says. “I did not know all that; I didn’t know about the roots. That, for sure, is a way we could save our country, our land. We are killing our land, and what we learned was truly amazing.

“I am excited to be able to do this,” she adds. “We never had all the input that we needed. We have the space, and we are gardeners, and we want to get back into taking care of Mother Earth. This sounds like a wonderful idea.”

Mitchell Honan prepares the ground to receive prairie grass seeds at Enemy Swim. Photo: Robin Bowen

Robin Bowen, a member of St. James, Enemy Swim, was impressed with the presentation on the Lake Traverse Reservation, which took place in October.

“This is our way to respect life, and to remember that everything has life,” she says. “Respect Mother Earth, respect the land, respect the animals … and you don’t do that by putting chemicals into it. We need to bring back the natural grasses and the trees, and they take care of the air, and it’s a circle … a circle of life that was fine before we got here.

“If we lose the animals and the fish and the water and air, the planet will die,” Bowen points out. “If we lose humanity, the planet will survive and probably flourish.”

John Eagle, a Native elder from Sisseton, was one of the presenters in Enemy Swim, telling the story of the land. “He was able to give a history of it,” Bowen says, “and was a really good speaker.”

Bowen’s husband, Smokey, believes that “going back to the natural prairie grass that used to be here before, I think, is kind of God’s will! Why are we trying to fix something that isn’t broke? Go back to the natural way.”

He adds, “When Jesus says to love thy neighbor as you love yourself, the whole creation is our neighbor. It’s not just who you can talk to and see as a human being, but the whole creation.”

Robin Bowen was impressed by the presentation. “I thought that Mitch was very informative about what we needed to do, and took us through the steps from the beginning of the summer … and made sure I had everything I needed. He was right there every time I had a question. He provided me with everything I needed to do this.”

Werger, she says, “was very informative; she knew what she was talking about and was able to answer questions from the people,” who came from Sioux Falls, Watertown, Mobridge, and Aberdeen to participate.

Julie Gehm, senior warden at Calvary Cathedral, traveled from Sioux Falls to Enemy Swim for the presentation.

“I thought it was really interesting,” she says. “It was a nice combination of science and spirituality, with Mia Werger talking about the science of native grasses and the super-long roots they put down and how that is good for the environment.

“The elder that spoke, John Eagle, talked about praying when planting, asking God or the Creator for the planting to be successful for the seeds to grow,” she adds. “He also told a couple of different origin stories for the name of Enemy Swim. And then the hospitality by the St. James congregation was … very generous.”

Gehm says that the sustainability of “Common Ground, Shared Roots” is “critical to the future of humanity. We need to be better about honoring Mother Earth, and make sure that the planet is habitable for our descendants. We owe that to God as well … that we are good stewards with God of nature.”

The Revs. Ellen and Kurt Huber, superintending presbyters of the Cheyenne River Episcopal Mission, say they were moved by the November presentation at St. John’s, Eagle Butte.

“The morning was filled with important conversations and deep listening,” Ellen Huber says. “Love and concern for Unci Maka (Grandmother Earth) flowed through all who gathered to learn and plant prairie grass seeds.”

“We were able to listen and learn about prairie grasses and the need for us to take action in this era of climate change,” Kurt Huber says. “Mia (Werger) was helpful in framing the grass seed and a return to native plants for churches, communities, and peoples.”

Harley L. Zephier Jr., a local Native presenter, was born in Faith and is Mnicoujou Lakota. He began his presentation by talking about growing up learning “about the importance of keeping our world alive, through belief and connection to Creator.”

Zephier “brought spirituality into the conversation through his participation in sun dances and living in a traditional way,” Kurt Huber says. “Each (presenter) helped us see our part on Mother Earth and a call to live in harmony with all of our relations. It felt like the Holy Spirit blew through our meeting.”

Honan has high hopes for the future of “Common Ground, Shared Roots,” because it allows so many people to participate. “I sincerely hope that the people who hear about this will be inspired to take small but powerful actions like this to protect the environment that our future depends on.”

“We literally and spiritually have planted seeds,” says Folts, “and we have faith that all these seeds will grow roots and that the roots will take. We know what to expect from the seeds that we planted in the ground. What will be really exciting to watch is to see what God will do with the seeds planted in people’s minds and hearts.”

Social Menu