How ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ went from a little-known poem to an Episcopal hymn and a cultural anthemPosted Aug 2, 2021 |

|

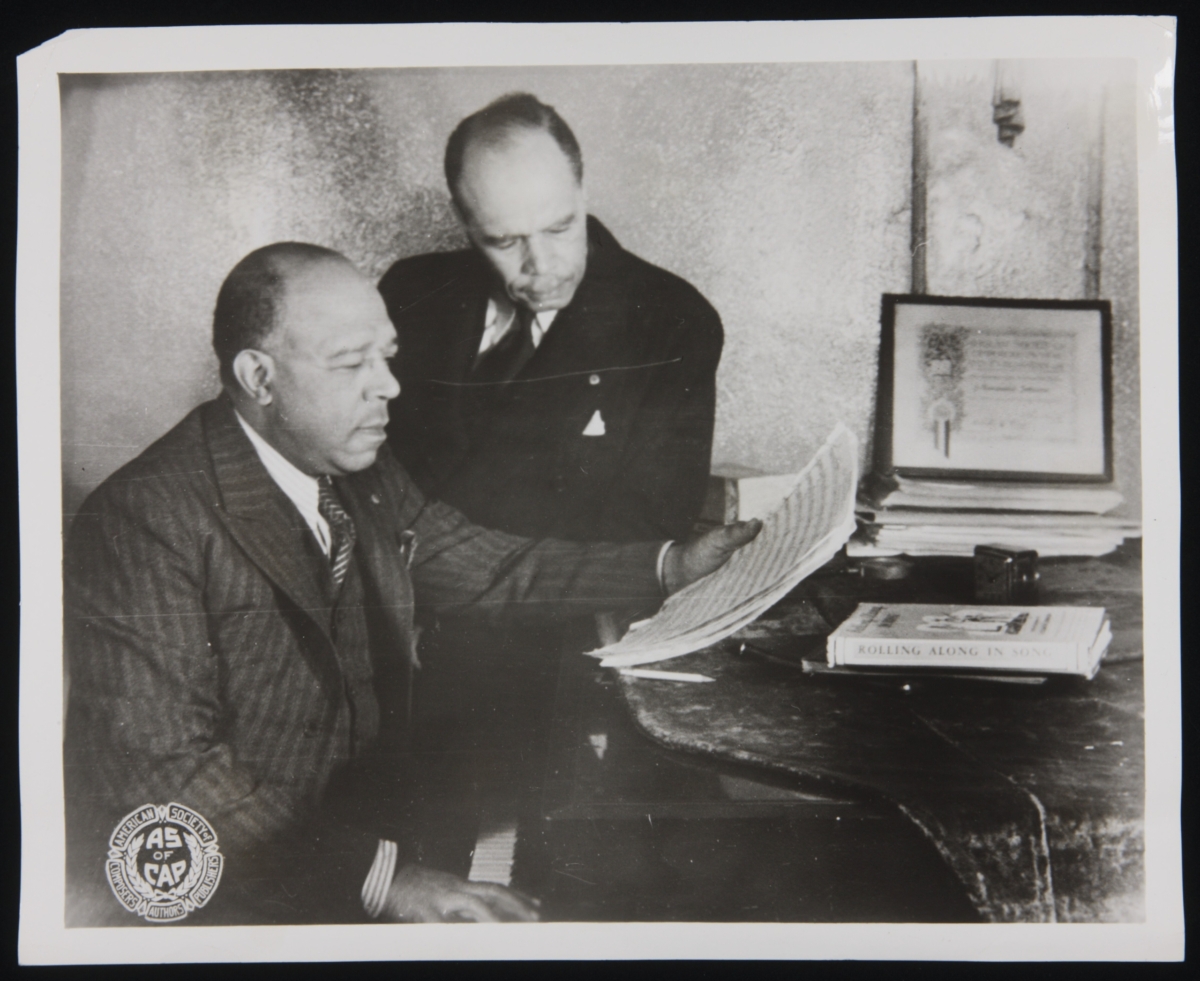

James Weldon Johnson, left, and J. Rosamond Johnson at the piano. Photo: Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

[Episcopal News Service] As the song known as the “Black national anthem” achieves wider recognition in the United States, its significance is also being celebrated in The Episcopal Church. “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” sung by generations of African Americans as a tribute to their struggles and triumphs, was introduced to white American Christians by Episcopalians and Lutherans 40 years ago, and a congressional bill endorsed by The Episcopal Church now proposes designating it as the U.S. national hymn.

Despite being a beloved African American anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was little known outside Black communities until the 1980s, when Black Lutheran and Episcopalian musicians pressed for its inclusion in their denominations’ hymnals. The song was included in the original version of the eponymous Episcopal hymnal compiling African American spirituals, which was originally released in 1981 as a supplement to the 1940 hymnal. It was then included in the standard 1982 hymnal, which helped introduce the song to a wider audience.

At its most recent meeting in June, The Episcopal Church Executive Council passed a resolution supporting a bill introduced earlier this year by U.S. Rep. James Clyburn that would make “Lift Every Voice and Sing” the official national hymn.

“I see this resolution, and this attempt in Congress, as a way to accept – on the part of this whole country – an offering of an important poem and song to all the American people, just like Black Episcopalians offered this song to The Episcopal Church,” said Byron Rushing, the vice president of the House of Deputies who sponsored the Executive Council resolution, at the meeting. Though the resolution passed, it prompted some debate about whether it was appropriate for a secular nation to have a national hymn – especially in light of the church’s efforts to counter rising Christian nationalism.

“A hymn is inherently Christian, by definition by the Encyclopedia Britannica. And it’s a song of praise to God,” the Rev. Mally Lloyd pointed out during the discussion on the resolution.

“I love to stand up and shout it. I love to declare it. But putting as a national hymn is where I am having trouble in terms of trying to encourage inclusivity and honoring of all of our nation.”

The song’s lyrics are not overtly Christian, but they do mention God and heaven several times. Despite its description as a hymn in Clyburn’s bill and its inclusion in hymnals, its origins are secular.

The lyrics were written by James Weldon Johnson – a Black man from Jacksonville, Florida, who became a leader in the Harlem Renaissance. Among other vocations, Johnson was a lawyer, a teacher, a poet, a diplomat and a civil rights organizer. He was the leader of the NAACP for 10 years, the first Black professor hired by New York University, and the U.S. consul to Venezuela and later Nicaragua. He and his brother, composer J. Rosamond Johnson, also together wrote about 200 songs for Broadway musicals.

In 1900, while serving as a school principal in Jacksonville, Johnson was asked to speak at a celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. Instead of a speech, he wrote a poem, which his brother then set to music. It was sung by 500 schoolchildren at the event, but the Johnson brothers didn’t think it would ever spread beyond that. They were wrong.

“The school children of Jacksonville kept singing it, they went off to other schools and sang it, they became teachers and taught it to other children,” Johnson recalled in 1935. Booker T. Washington helped popularize it, its lyrics were printed in Black newspapers and it was selected as the official song of the NAACP.

“Within twenty years, it was being sung over the South and in some other parts of the country. Today the song, popularly known as the Negro National Hymn, is quite generally used. The lines of this song repay me in elation, almost of exquisite anguish, whenever I hear them sung by Negro children,” Johnson wrote.

It is not clear whether Johnson ever considered himself an Episcopalian, but he did help organize the 1917 Silent Parade in New York, in which about 10,000 African Americans marched down Fifth Avenue in protest against lynchings and racist violence, along with leaders from St. Philip’s Church, the oldest Black Episcopal parish in New York. Today, Johnson is included on The Episcopal Church’s Holy Women, Holy Men calendar, commemorated on June 25.

Though “Lift Every Voice and Sing” enjoyed a resurgence in the late 20th century due to its inclusion in church hymnals, it was sung in earlier decades at Black secular events as well as churches, Rushing told Episcopal News Service.

“Black churches always sang it, but when I was growing up, you couldn’t go to a large meeting of Black people where they didn’t sing it, either at the beginning or the end,” Rushing said. “It was always seen as a secular song.

“The other custom that Black people had was they always stood” while they sung it, Rushing added, “and there would be events where people sang both the national anthem and this.”

During discussion of the resolution at Executive Council in June, member Diane Pollard also recalled hearing it in both religious and non-religious contexts, and that it was revered in a way similar to the national anthem.

“I was taught that when this song is sung, you stand up,” Pollard remembered. “And my grandmother was not telling me to stand up because it was a song from the church. Far be it; many churches were the last to get on the bandwagon with equality for nonwhite people. She was telling me to stand up out of respect.”

The song has enjoyed new popularity in recent years from secular sources again, largely due to the Black Lives Matter movement. Beyonce performed it at the Coachella music festival in 2018. The NFL will play it before all games this season, after doing so during a week last year. And in January, the legislation to make it America’s national hymn was introduced in the House of Representatives.

Making it the national hymn “would be an act of bringing the country together,” Clyburn said when introducing the legislation. “The gesture itself would be an act of healing. Everybody can identify with that song.” Episcopalians can learn more about how to support the legislation at the Episcopal Public Policy Network.

Rushing said he was approached by Carl MaultsBy, the director of music at St. Richard’s Episcopal Church in Winter Park, Florida, encouraging the church to adopt a resolution supporting the bill. Rushing added that while he understands the concerns about adopting a “national hymn,” he said the word “hymn” in this case is only used because no song except “The Star-Spangled Banner” can be called a national anthem in the U.S.

“I understand the difficulty with the word ‘hymn,’” he said during the Executive Council meeting. “I think that if you ask most Black people what they would call this, they would have said an anthem. But that, of course, creates a slight problem in this legislation if we use that term. … We’re recognizing an important song in American culture.”

The Rev. Charles Graves IV, another Executive Council member, also argued in support of the resolution, saying that there are already other national symbols that invoke God, but the purpose of Clyburn’s legislation is not religious but cultural and educational.

“We’re in the middle of this conversation about critical race theory and what will be taught in schools in terms of the history of race and the current realities of race in this country,” Graves said. “And so adding this hymn to our national canon helps to ensure that in the same way that schoolchildren are taught about the bald eagle and taught about the Constitution … they will also be taught about James Weldon Johnson and about the struggle out of which he wrote this hymn.”

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu