Churches in the nation’s capital seek to balance welcome and securityPosted Feb 25, 2021 |

|

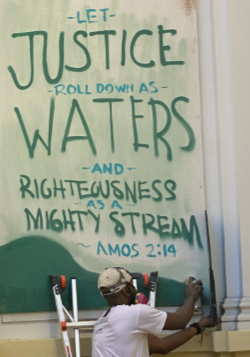

The artists of Washington, D.C’.s, P.A.I.N.T.S. Institute spent Sept. 5, 2020, creating vivid, social justice-themed images on the plywood-covered stained glass windows at St. John’s Episcopal Church near the White House. Photo: Rachel Jones/Faith & Leadership

Editor’s note: P.A.I.N.T.S. Institute founder John Chisholm, who is quoted in this article, died unexpectedly before publication.

[Faith & Leadership] A war-weary Abraham Lincoln sought solace in one of its weathered pews, and Franklin D. Roosevelt prayed for guidance inside its domed sanctuary. In fact, every sitting president since James Madison has attended at least one service at St. John’s Episcopal Church, earning the Greek Revival-style house of worship its nickname: “the Church of the Presidents.”

Since its opening in 1816, St. John’s has also amassed a long tradition of community engagement and equal rights advocacy, something the Rev. Robert Fisher wanted to emphasize when he became rector in June 2019.

The Rev. Robert Fisher and John Chisholm stand in front of a painting of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Photo: Rachel Jones/Faith & Leadership

So he asked his congregation: How can we let our neighbors know that St. John’s is as much a sanctuary for them as for any president?

It’s safe to say that barricades and boarded-up windows were not the look they were going for.

Unfortunately, that’s been the reality for St. John’s since June 2020, after someone set a fire in the church’s basement amid protests over the murder of George Floyd. Even then, the church pledged to serve as a safe space for protestors, hosting prayer vigils and providing water, food and hand sanitizer to the thousands who filled the streets in support of racial justice.

But several weeks later, after acts of graffiti and a growing encampment on church grounds, St. John’s reluctantly agreed to the district’s plans to erect 8-foot fencing around the property.

Although the church’s history, location and recent events make it unique, churches in cities across the country struggle with the same issues: how to make the physical space both secure and welcoming.

Church leaders reluctantly agreed to security measures such as fencing around the church property. Photo: iStock/miralex

“All of us — the bishop, the wardens, me — hated the idea of a fence and reluctantly said OK because we felt it was the responsible thing. The buildings are a ministry, and we didn’t want to see that building go away. It’s important to me that it lives to serve future generations,” Fisher said. “But it was an extremely uncomfortable thing.”

Since then, Fisher and his congregation have done their best to get out from behind that fence, reaching out to neighborhood activists with offers of support and solidifying relationships with organizations that can help them better serve their community.

That includes a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that recruited local artists of color to paint images of healing and hope on the plywood that conceals the church’s stained-glass windows.

Eight months after the barriers went up — Fisher still comes and goes through a padlocked gate — the stunning works created by artists affiliated with the P.A.I.N.T.S. Institute are like a salve on an open wound.

Artist Shawn Perkins created two murals, including this serene pastel Madonna, during the painting day at St. John’s. Photo: Rachel Jones/Faith & Leadership

Having barricades around the church has been heartbreaking, Fisher said. But it has also forced the congregation to build bridges where they hadn’t previously existed, an effort Fisher called a “heart-opening experience.”

What relationships does your organization have that are better than fences?

“Relationships are better security than fences, and we now have deeper and more meaningful relationships than a year ago,” Fisher said. “Those bless us and help us be a better church serving the community.”

‘You’ve been vulnerable for so long’

A steady presence at 16th and H Streets NW for more than 200 years, St. John’s is within sight of the White House. In retrospect, said longtime member Chase Rynd, its location may have given the congregation “a misplaced sense of security,” what with FBI headquarters a few blocks away and Secret Service personnel right across the street.

It wasn’t as if the church had never thought about safety planning, said Rynd, who is also the retired executive director of the National Building Museum. About a year and a half before the fire, renovations to the church’s parish house reconfigured the entrance so visitors would encounter a greeter at a reception desk rather than an empty hallway, and a new elevator was installed that required security badges, said Rynd, who chaired that effort.

The project also added a 21st-century fire protection system, including fire doors that have been credited with limiting damage from the 2020 incident. Federal officials continue to investigate the fire.

A security assessment subsequently underwritten by the DowntownDC Business Improvement District concluded that St. John’s had gotten lucky, Rynd said. The DowntownDC BID is one of 11 special taxing districts in the city that support economic development and social services.

“[The assessment] basically said, ‘You guys have skirted through history with an enormous amount of luck or protection from God or whatever, because you’ve been vulnerable for so long,’” Rynd said.

A surreal moment

On June 1, the day after the fire, clergy, parishioners and volunteers from throughout the region gathered on the patio of St. John’s to offer first aid, snacks and water to protestors.

Levi Robinson paints a Scripture passage to accompany his sprawling image of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the centerpiece of the murals. Photo: Rachel Jones/Faith & Leadership

In an interview with Fox News host Martha MacCallum that evening, Fisher was expressing continued support for those rallying for justice when he learned that police were using tear gas and rubber bullets to clear people gathered around the church so then-President Donald Trump could stage a now widely criticized photo op.

“We seek to be a space for grace in this city,” Fisher was saying on camera as the surreal moment played out. “We strive to make it so that the space, when you walk in the door, whatever background you may be, you feel that it’s a place where you can breathe, where you can experience the Spirit.”

The next morning, federal officials began fencing off Lafayette Park across the street, barring access to one of the country’s most storied protest sites and essentially pressing demonstrators up against the walls of St. John’s. Protestors set up camp on the church’s tiny property, next door to the newly established Black Lives Matter Plaza, raising concerns about sanitation, staff access and fire safety, Fisher said.

Church officials planned to sit down with protestors to address some of those concerns, he said, but before that could happen, police forcefully cleared everyone from the property, arresting those who resisted and tossing their tents, bicycles, laptops and other belongings into a pickup truck.

“It was a really tough thing to have happen around our church,” Fisher said. “The church hadn’t asked for that.”

St. John’s has been encircled by a fence ever since. No one likes it, but Rynd acknowledged that it has bought some time to come up with a better, more long-term plan.

“The fence just broadcasts such a poor message, but we didn’t sort of put up barricades and hide,” Rynd said. “We took this as a message that we need to be really attentive and seize this as an opportunity. In the end, the church is going to be better for it, in terms of the look of it and the way we use it.”

Rynd is now part of a small task force, which includes a combat veteran and several church members with State Department security training, charged with prioritizing the recommendations made in the church’s security assessment.

To ensure that any physical changes to the church’s property are in keeping with both its aesthetic and its ethos, Rynd reached out to landscape architect Laurie Olin, whose firm had designed subtle yet effective post-9/11 security improvements for the Washington Monument, keeping the experience of visitors in mind. Olin agreed to create a master plan for the church “for almost nothing,” Rynd said.

In addition to physical improvements, the task force is looking at policies governing who has access to St. John’s and whether staff and volunteers might benefit from more training on how to spot potential security issues while engaging with visitors.

“This is a really important piece of, ‘How do we both address the security of the building and still have our arms wide open and welcome people?’” Rynd said.

Artist Mohammed Gafar chose to feature the symbol of a dove for his mural. Photo: Rachel Jones/Faith & Leadership

A security assessment to identify vulnerabilities is the right place to start the process, said Mike McCarty, the CEO of Safe Hiring Solutions, an Indiana-based company with a program geared toward ministries.

How do people come and go from the building, who has access, and when? How are children checked in and out of youth programs? Is the congregation prepared for medical emergencies? With so much religious life online during the pandemic, is the congregation cybersecure?

Answers to those questions help congregations focus their efforts, and that kind of forethought allows faith communities to put measures in place that address risks while honoring their culture, he said.

In many cases, including at McCarty’s own nondenominational church, congregations create lay-led security teams.

“Being prepared doesn’t have to look militant. A lot of times, it’s just being educated and having the right team,” McCarty said. “A lot of it is more sweat equity than expensive solutions.”

Other churches also grapple with security concerns

At Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, several blocks north of St. John’s, hospitality and security have never been mutually exclusive, said the Rev. William H. Lamar IV. As a predominantly Black congregation in America, Metropolitan has always been mindful of who gathers near its 135-year-old building; that’s ingrained in the congregation’s DNA, he said.

When members of the far-right Proud Boys descended on Washington for pro-Trump rallies in early December, they stole and destroyed the church’s Black Lives Matter sign — but never gained access to the building, Lamar said.

“We’ve been schooled to pay attention, because there is a constant threat,” he said. “We’ve got to be vigilant. … We open our hearts. But we’re not going to be sitting ducks.”

To that end, Metropolitan AME partnered with a security firm in a way that Lamar describes as more of a relational undertaking than a contractual one. Blowout Security’s owner, Leon Russell, was already a longtime friend of many in the congregation, and as head of security at his own Washington church, historic 19th Street Baptist, he understood the balance between securing the premises and preserving its feel as a house of worship.

Russell’s security team worships alongside Metropolitan AME’s congregants. Team members escort seniors to their cars and are on a first-name basis with worshippers, who have been known to bake them cookies, Russell said. They are vigilant, often armed, and treated as family, he said.

“What we’re trying to do here is set everyone at ease,” said Russell, a Vietnam veteran. “I don’t want uniforms in there and for it to look like it’s a fortress. It’s a sanctuary. It’s where we pray.”

McCarty recommends that congregations seek guidance from their insurance companies to establish safety protocols. And both men noted that it’s important to communicate regularly to the congregation that safety planning is happening, without broadcasting the specifics — for obvious security reasons.

About three blocks east of St. John’s, New York Avenue Presbyterian Church is known for its protestor hospitality. But it, too, has had to balance that hospitality with safety.

In June, members of the church’s session, its governing body, met daily via Zoom to discuss how they could safely support demonstrators amid the pandemic, serve as a resource for neighboring congregations of color, and continue to host the popular Downtown Day Services Center, which provides resources including food and medical care and shower and laundry facilities for the city’s homeless and vulnerable populations.

“We’ve been in the thick of it,” said the Rev. Dr. Heather Shortlidge, the church’s transitional pastor, who recalled helicopters skimming over the church’s steeple and “roving packs of law enforcement, some of them un-uniformed and unbadged” at the height of the protests.

The session wrestled with who should be allowed inside the church during the unrest and ultimately decided that only unarmed individuals could enter, Shortlidge said. That meant law enforcement could not come inside, an issue that remains “unsettled” for the congregation, she said.

“That’s been really sticky for us. You want to say, ‘Everybody is welcome,’ but we also felt we needed to start to have boundaries,” she said.

“Radical hospitality is not ‘anything goes,’ which is hard for a bleeding-heart liberal congregation to swallow. But it’s not radical hospitality if people aren’t safe.”

‘You cannot waste a crisis’

First United Methodist Church in Charlottesville, Virginia, adopted a similar stance in August 2017, serving as a respite for activists countering the Unite the Right rally and a home base for street medics and trauma counselors, said the Rev. Phil Woodson, the associate pastor.

Two years earlier, after a white supremacist shot and killed nine worshippers inside Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, clergy in Charlottesville had begun organizing. They created the interfaith Charlottesville Clergy Collective, which began meeting regularly, learning how to engage in nonviolent resistance and work together to keep people safe amid confrontation.

“You cannot waste a crisis. You must grow in these times of trial. Otherwise, you’re spiritually dead,” Woodson said.

“For as much evil and horror as went on that day, the goodness that came out of it is that relationships have thrived among people in the community. I don’t see any future where these Nazis show back up to Charlottesville. But if they did, I’d like to think the people in this place know what to do and how to do it,” he said.

At St. John’s, Fisher is celebrating new relationships, too. In partnering with the DowntownDC BID to complete the church’s security assessment, the congregation was introduced to the broad range of services the organization offers.

Before the protests — and the fencing — several homeless people used to sleep on the church’s porch at night, which wasn’t a problem for St. John’s but “probably wasn’t best practice,” Fisher said.

In retrospect, he said, those folks might have been better served if the church had connected them with the Downtown Day Services Center, which is managed by DowntownDC BID, at nearby New York Avenue Presbyterian — something they intend to do from now on.

The DowntownDC BID also helped link the church with the P.A.I.N.T.S. Institute, a nonprofit that serves as an incubator for local artists and a support for underserved communities. The murals created by P.A.I.N.T.S. — which stands for Providing Artists with Inspiration in Non-Traditional Settings — are catalysts for conversation, founder John Chisholm said.

Indeed, as the artists toiled in the hot sun outside the church in early September, among the most beautiful of spectacles were the dialogues sparked between the artists and congregants, activists and passersby, he said.

In “normal times,” said Fisher, when roughly 400 worshippers would gather in the sanctuary each Sunday, the light streaming through the stained-glass windows would wash over them, bathing them in a swirl of color “like a blessing.”

In such a time as this, he said, the murals project love and light outward, a sign of God’s promise of better things to come and the church’s pledge to be part of that. The Smithsonian has expressed an interest in displaying the murals once the stained-glass windows are uncovered, Chisholm said.

“What the paintings do is cause people to look up and find hope. Because if you’re not looking up, you’re going to be looking down. Despite the barriers, our hearts were never this at any moment,” Fisher said, gesturing to the fences. “Our disposition didn’t change just because the architecture changed.”

This story was originally published by Faith & Leadership and is republished here with permission.

Social Menu