Thousands join three-part Becoming Beloved Community NOW webinars on racial justicePosted Jul 31, 2020 |

|

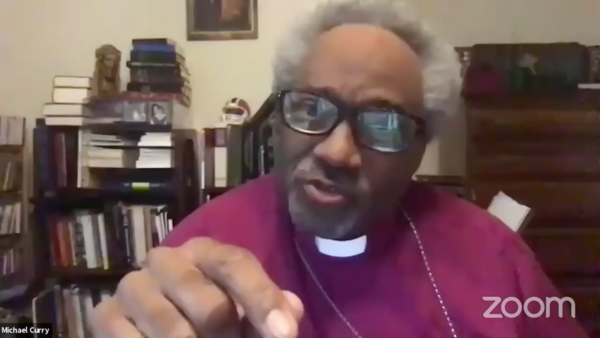

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry speaks July 28 during the first session of Becoming Beloved Community NOW, which was hosted on Zoom and livestreamed on Facebook.

[Episcopal News Service] The Episcopal Church’s Becoming Beloved Community NOW, a three-part series of webinars on different aspects of the church’s racial reconciliation work, was overwhelmed by interest in the Zoom sessions this week, both in registrations and in replay of the videos on Facebook.

The webinars were hosted July 28-30 by a church committee known as the Presiding Officers’ Advisory Group on Beloved Community Implementation, which sought to harness the momentum across the church generated by recent nationwide protests against racial injustice and police brutality. The webinars’ views indicate that momentum hasn’t subsided.

Nearly 1,700 people registered for the July 28 webinar, which explored the theme “Truth,” and of those registrants, 1,293 people logged in through Zoom. It also was livestreamed on Facebook to accommodate more people. One way to put those numbers in context: If the “Truth” webinar were a congregation, its attendance topped the official average Sunday attendance of all but four congregations across the whole Episcopal Church.

More than 2,500 people have viewed a minute or more of the Facebook video of that first webinar, which featured remarks by Presiding Bishop Michael Curry. The Rev. Gay Clark Jennings, president of the House of Deputies, appeared July 29 during the second session, on “Justice,” which drew about 1,150 participants and more than 800 Facebook views of a minute or more. And more than 900 logged into Zoom for the third session, on “Healing,” generating 600 Facebook views of at least a minute.

“Jesus came into the world to testify to the truth,” Curry said, setting the tone for the first discussion. He invoked Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s words on the subject: “Truth-telling and healing our history is the only way to save our country, to save our world. It’s the only way to do it,” Curry said. “And yet truth-telling is not the goal. It is a means to the goal. Like any nonviolent approach, it is the means, not the end, and it is important to keep the end in mind.”

The “end” that Episcopal leaders have in mind is becoming the Beloved Community, a concept popularized by Martin Luther King Jr. to represent his vision for a society lifted up in racial harmony. The Episcopal Church has spoken against racism for decades, and in 2017, it launched the Becoming Beloved Community framework to help dioceses and congregations be a part of the work to achieve King’s vision.

Jennings, though, said the church historically has not always been unified or aggressive in taking those necessary steps. Sometimes, its General Convention had to be pushed to do the right thing.

“There have been leaders in our church, particularly Black, Indigenous, Latino and Asian leaders, who have been calling us all to this work for many, many years. These calls have too often gone largely unheard, ignored or even forgotten,” Jennings said during the July 29 webinar. “But the Holy Spirit and those General Convention leaders have been pointing toward a vision of Beloved Community for many decades now, and their wisdom in the form of scores of resolutions lights our path today.

“This is the time, particularly for white members of The Episcopal Church, to repent of our failure to listen and to commit ourselves fully to that vision.”

The May 25 killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota, has inspired some Episcopalians to join other Americans in condemning systemic racism, seen as the root of police brutality and other violence toward people of color in the United States. The church’s Becoming Beloved Community NOW webinars were offered as one resource to help those Episcopalians turn interest and awareness into action.

You can watch videos of the sessions on Facebook:

At times, the success of the two-hour webinars posed unexpected challenges to organizers. Participants who signed up and logged in through Zoom were to be assigned to breakout rooms for small-group discussions during part of each session, but Zoom doesn’t allow breakout rooms for such a large turnout. Even so, participants were able to use other tools to send in questions for the presenters and share their thoughts digitally, and viewers on Facebook could comment in real time.

During the first day’s session, Chris Graham spoke of his work with the History & Reconciliation Initiative at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, once known as the Cathedral of the Confederacy, in Richmond, Virginia. Cynthia Copeland of the Diocese of New York’s Reparations Committee explained what she called “ground truthing,” or researching the long-hidden and often uncomfortable truths about a church’s historic interactions with people of color.

“Take a look at, Who are these people that got us started? Who are our original vestry members? Who are our founding people?” Copeland said. “What was their connection to slavery? … How did we, and the broader Episcopal Church, how did we benefit from our role in this thing called slavery?”

In the second session, which offered examples of the church’s social justice work, speakers included Catherine Meeks, executive director of the Atlanta, Georgia-based Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing, and the Rev. Charles Wynder, The Episcopal Church’s staff officer for social justice. The Rev. Peggy Bryan, a priest at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in California’s Silicon Valley, described the Stepping Stones ministry she leads among local jail and prison inmates and those reentering society after release from incarceration.

The third session highlighted a variety of experiences with racial healing among speakers from Indigenous, Latino and Asian American communities. House of Deputies Vice President Byron Rushing spoke of some of his work in the 1960s as a community organizer supporting Black residents of Boston, Massachusetts.

As one example, Rushing told the story of his interest in helping people in the impoverished neighborhood of Roxbury fight for better housing. The residents told Rushing that, instead of better housing, they wanted his help cleaning up a park in the neighborhood where suburbanites had been dumping their garbage to avoid paying for its disposal.

The residents and Rushing developed a plan to pile up all the garbage in a big mound, hoping to draw attention of city officials to the problem. Someone suggested setting the pile on fire to amplify their point. With the garbage blazing, city firefighters came and aimed their hoses not just at the fire but also at the residents. Shocking photos of the scene in the next day’s newspaper were enough to get the city finally to address the park’s garbage problem.

“What I learned from that was listening to people and being patient with their response,” Rushing said. “I find this the center of healing. … What has helped me is to engage in a process, in a process of believing that other people know as much or more than I do about themselves, and listening to them and attempting as best as possible to do and help them in what they ask.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu