‘All Saints’ movie details how refugees saved struggling Episcopal churchPosted Aug 25, 2017 |

|

Besides Ye Win’s starring role, all the Karen parishioners in “All Saints” were real parishioners at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Smyrna, Tennessee. Photo: “All Saints” via Facebook

[Episcopal News Service] After a split over theology in the 1990s, there were only 12 members of the congregation left at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Smyrna, Tennessee, a suburb south of Nashville. The church couldn’t pay its mortgage. By 2007, the church was in danger of closing.

Today, 130 to 150 parishioners attend Sunday services. Many worshipers filling those pews – barefoot after leaving their flip-flops at the door – are Karen refugees, an ethnic minority from Burma (called Myanmar by its military government). The church’s mortgage is paid off. It even has a community farm now.

At All Saints’, it was the refugees who saved the Americans.

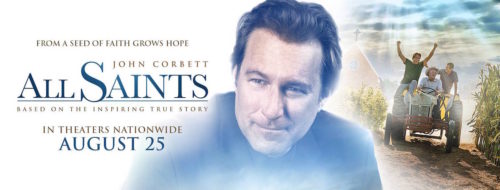

Los Angeles director Steve Gomer found the transformation of this struggling Southern congregation so inspiring that he moved his family to Nashville to create a fictionalized film about it. The Sony Pictures movie “All Saints” opened Aug. 25 in 800 theaters nationwide, starring John Corbett (“Northern Exposure,” “Sex and the City” and “My Big Fat Greek Wedding”) as the real-life Rev. Michael Spurlock, Cara Buono (“Mad Men” and “Stranger Things”) as Spurlock’s wife, Aimee Spurlock, and Nelson Lee (“Law & Order,” “Oz” and “Blade: The Series”) playing Ye Win, a Karen leader.

Inspired by the Karen refugee story at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Smyrna, Tennessee, the Sony Pictures film “All Saints” releases nationwide Aug. 25 and in Europe and United Kingdom the week afterward. Photo: “All Saints” via Facebook

“The real story is remarkable. We had to change very little to make it dramatic,” Gomer told the Episcopal News Service. “You have these extraordinary people who went out of their way to say, ‘Yes, we’re here. Let’s form this community.’ I think the picture is moving but honest. It’s not saccharine.”

A lifelong Anglican, like many Karen, Ye Win and other refugees showed up at the church in 2007, asking to farm some of the church’s 20 acres to feed their families. More than 100,000 Karen live in a refugee camp on the border of Thailand and Burma. The ongoing civil war has earned them refugee status in the U.S., and they receive government support for three months after arrival. Then, they’re largely on their own.

The Trump administration’s temporary refugee ban makes this film even more timely, said the Rev. Robert Rhea, part-time vicar at All Saints’ since June 2016 and a full-time emergency-room physician. This is his first appointed post since graduating from Nashotah House Theological Seminary.

“The film has a broader impact for all Christians and faith communities. What do we do with the refugees and immigrants in our midst? How do we reach out and welcome them as God wants us to?” Rhea asked.

In the film, as in life, businessman-turned-pastor Spurlock had arrived recently at the church when Ye Win showed up. Spurlock had planned to close the struggling church. But the Karen’s farming of spinach, sour leaf and other foods not only fed their families, it helped the congregation. They were able to sell the extra crops at nearby markets to help pay the church’s bills. Yet everyone had to pitch in.

“Nobody knew what we were getting in for, as far as labor,” the real Spurlock said in a clip. “It is back-breaking work.”

The film crew shoots a church service for “All Saints,” a feature film out Aug. 25 in theaters across the United States. Photo: “All Saints” via Facebook

To research the film, Gomer attended services and family dinners. He participated in pastoral duties, such as transporting Karen people to doctor’s appointments and tutoring. Gomer is Jewish and active in his synagogue, but he’d been interested in doing a film that he cared about, something showing the difficulties clergy members experience.

“At dinner at Ye Win’s house, my wife and I realized we were sort of in a time machine. We were sitting with our great-grandparents from Russia, who had a very similar experience in the 1890s as refugees and immigrants,” Gomer said. “That’s who the United States is. Building community. This is our story, and it’s any refugee’s story, although there are special circumstances in this story to make it even better.”

These days, there’s one Sunday service with the homily preached in both languages, as are the prayers and hymns.

Lisa Lehr moved to Smyrna in 2013. She wasn’t Episcopalian but decided to join the church after a Karen woman from All Saints’ hugged her on Palm Sunday in 2014.

“They made me feel like I was there with them, that they were my community, or they could be my community if I accepted it, and I did,” said Lehr, a volunteer Christian educator and now a member of the All Saints’ Mission Council.

The Episcopal Diocese of Tennessee, led by Bishop John Bauerschmidt, is sponsoring a special free showing of the film Aug. 26 for members of the diocese. At the premiere on Aug. 3, all the stars showed up on the red carpet, with cameras and hoopla. During the film’s credits, viewers can see clips of the real congregation and what they’re doing today.

“People, not particularly Christian, I hope they will see it and be moved,” Rhea said. “This story is very, very appropriate for these times.”

— Amy Sowder is a special correspondent for the Episcopal News Service, and a writer and editor living in Brooklyn, New York.

Social Menu