Church in Charleston, South Carolina, sponsors historical marker detailing 1919 anti-Black riotPosted Dec 14, 2023 |

|

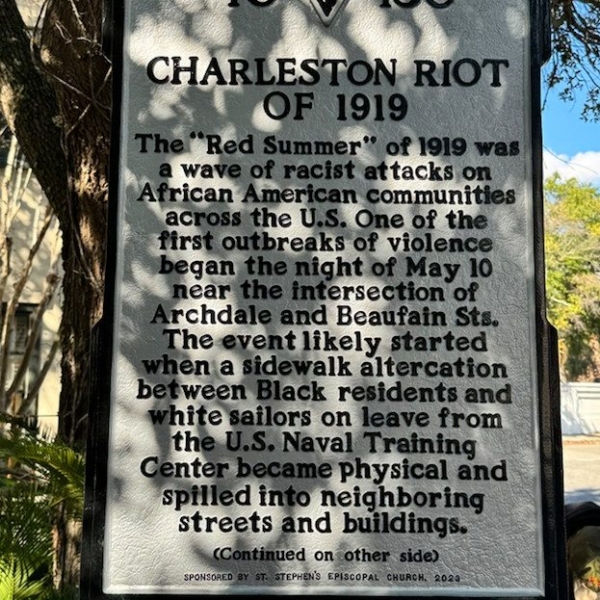

[Episcopal News Service] A 1919 riot in which white sailors in Charleston, South Carolina, attacked Black businesses and residents, killing two, was little known to many in the congregation at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church despite the 200-year-old church’s downtown location blocks from where the historic violence started.

Then last year, several dozen St. Stephen’s parishioners and members of other downtown congregations embarked on a civil rights pilgrimage. They traveled to sites in Alabama that were significant in the fight against racial segregation and discrimination in the 1950s and 1960s, such as the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham and the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

City and faith leaders unveiled the sign marking the 1919 Charleston riot in a ceremony on Nov. 29. Photo: St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, via Facebook

When they returned to Charleston, parishioner Barbara Pace and others from St. Stephen’s wanted to raise awareness of past racial injustice in their own city. After researching the May 1919 outbreak of anti-Black violence in Charleston, the church sponsored a new historical marker detailing the riot. The marker was unveiled at the end of November in a ceremony attended by city and faith leaders.

The sign that now tells the story of this “not-so-well-known history” is displayed prominently “in a spot where tourists as well as residents walk,” Pace told Episcopal News Service. She hopes it will make a difference in the public’s greater understanding of “the puzzle of American history.”

The congregation worked on the sign’s wording with historian Damon Fordham, who previously had researched the 1919 riot. Though its precise cause is lost to history, Fordham found accounts suggesting that the white sailors started their May 10 rampage over the $20 they gave a Black man to buy them some liquor.

“The sailors angrily searched a nearby Black restaurant for the man and this led to fights and the soldiers throwing everything they could pick up in the restaurant during the melee,” Fordham wrote in an article for a Charleston history website. A Black barbershop was destroyed, and the sailors shot and killed two Black men, Isaiah Doctor and William Brown.

The unrest was quelled only after the city’s mayor called in members of the U.S. Marines to assist city police. Afterward, Black leaders demanded reforms, including the addition of Black police officers to the force, creation of a biracial city committee, arrests in the killings and compensation for the victims of the sailors’ attack.

“The Charleston Race Riot of 1919 showed Black resistance to the racial violence of that time and provided the local civil rights movement with some of its first small victories,” Fordham wrote.

The historical marker detailing the Charleston riot of 1919 was sponsored by St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church after members completed a pilgrimage to civil rights sites in Alabama in 2022. Photo: St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, via Facebook

The Charleston riot also marked an early episode in what came to be known as the “Red Summer” of 1919. Violence broke out between white and Black residents in more than two dozen American cities that year. Rising tensions were partly driven by the release of large numbers of military service members of all races back into civilian life after World War I.

Documenting details of the Charleston riot was crucial to winning approval from state and local authorities to erect the historical marker, Pace said. While those applications were pending, St. Stephen’s also conducted a successful fundraising campaign for the $2,500 needed to purchase the sign.

The congregation of about 500 members, with typical Sunday worship attendance of about 200, is known for being active in the community and supporting social justice causes, the Rev. Adam Shoemaker, St. Stephen’s rector, told ENS. And with the International African American Museum opening in Charleston in June 2023, the timing seemed right for the congregation to help create new awareness of the century-old riot.

“I do think that Charleston, South Carolina, specifically has a responsibility to try to tell the whole story of the history, of our collective history, pertaining to race,” Shoemaker said. He noted that the Confederacy’s first acts of secession were passed in Charleston, and the city had been a major port in the transatlantic slave trade.

St. Stephen’s and the Diocese of South Carolina also are “trying to uncover the full history of The Episcopal Church’s role in regard to racial relations and the institution of slavery,” Shoemaker said. He is involved in such diocesan efforts as co-chair of the diocese’s Racial Justice & Reconciliation Commission, with support from Bishop Ruth Woodliff-Stanley.

As for Charleston, “the city is doing its work” too in confronting troubling facts about its past, Shoemaker said. In 2018, for example, its City Council passed a resolution formally apologizing for Charleston’s historic role in slavery.

At the same time, “I think that there’s still a lot of work to be done in terms of uncovering the whole truth,” Shoemaker said, and the historical marker detailing the 1919 riot is one more step forward.

– David Paulsen is a senior reporter and editor for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu