What can cash-strapped churches do to enable youth ministry?Posted Apr 15, 2013 |

Here are some suggestions from youth ministers for how congregations with limited financial resources can enable or strengthen their ministries to and with young people.

Suggestion #1: Replicate the summer camp model

The idea might sound overly romantic until you consider that most camps operate on shoestring budgets. And you will also want to consider the findings of Church Divinity School of the Pacific seminarian, the Rev. Liz Tichenor, whose M.A. thesis focuses on the workers, ages 16–25, who staff summer church camps.

“I found that most are super engaged and excited about their faith, but the rest of the year a lot of them have almost nothing to do with church,” she says. “I wanted to dig deeper to see what it is that makes church camp so fruitful at offering spiritual dimensions, and what was missing for them at church.”

Before discussing her study, Tichenor points out that, compared to churches, camps have it easy. “Forming relationships is easier when fun is the focus.”

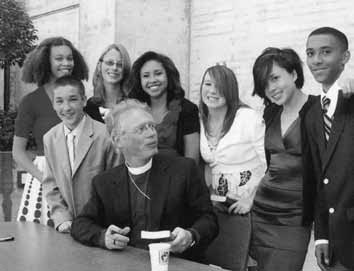

That sense of intimacy felt at summer camp can be replicated in vibrant church youth groups that are run by leaders who have strong backing from the rector and laity. Photo/CDSP

However, drawing from one of her findings, she explains that whether in camp or youth group, fostering deep relationships among participants is key to making a group cohere.

“Relationships are how young people make sense of the world and how they figure out who they can become.”

That sense of intimacy felt at camp can be replicated in vibrant church youth groups that are run by leaders who have strong backing from the rector and laity.

The bottom line for churches: It’s not about money as much as it is about commitment and a willingness for volunteers to pitch in and help the youth director, so that he or she has time to develop trusting relationships with participants, which in turn allows for a sense of intimacy among participants.

Katie Evenbeck, the director of St. Dorothy’s Rest, a camp and retreat center in Camp Meeker, California, recommends looking for a youth leader who has an understanding of group dynamics. “This person also needs to have a capacity to think strategically about community development, and know how to network.”

She also stresses the importance of accessing a candidate’s skills in interpersonal relationships. Someone might want to ask, for instance, how this person made a relationship work with a difficult co-worker.

The ability to work with difficult people can make all the difference in developing trusting relationships. During the 1980s, Betty Kasson assisted in the founding of B.R.E.A.D. Camp in the Diocese of California. She recalls a seventh-grade camper who was universally disliked by all. “He was like a stinging gadfly, always rude, always in your face,” she says.

After praying over this situation, staffers decided that if this truly was going to be a camp where kids could feel they wouldn’t be judged on the basis of who was most athletic, or pretty, or smart or by any typical standards, “then we would have to love him through his issues by ignoring his bad behavior and including him in every possible way.” She chuckles. “It wasn’t easy.”

To their delight, the boy blossomed. And he came back every year, eventually becoming a counselor.

These kinds of experiences benefit other campers too, says St. Dorothy’s Associate Director Malcolm McLaurin. For this reason, he says, it is important for youth leaders to “live up to the Baptismal Covenant and respect the dignity of every human being.

“Young people like to try on different masks, and it feels safe for them when they know whoever they are they will be respected.”

Tichenor continues with a few more of her findings: “Camps also encourage and honor the budding independence of young people. At camp, they are seldom seen as anything less than full members of the community.”

The bottom line for churches: Make sure the youth are integrated into the life of the church. St. Stephen’s Hudak recommends asking the youth director to attend every Sunday morning service and to make announcements, including mentioning upcoming activities and thanking parents for donations and support.

Tichenor’s expertise in developing spiritual energy and commitment in youth groups has generated interest. After graduation, she and her husband, Jesse Tichenor, a Montessori teacher, and Alice, their toddler, will relocate to Galilee Episcopal Camp and Conference Center, on the Nevada side of Lake Tahoe. She will serve as resident priest, while her husband will serve as the program director, with a shared goal of creating a year-round youth ministry.

She offers a final observation from her study: “What the youth counselors most valued was not the kayaking or games. What made camp special was the ethos, the orientation of the camp toward an intentional religious community, giving them a chance to live into what was preached.”

The bottom line for churches: Social activism matters to teens and parents. Youth groups seem to thrive when encouraged to participate in volunteer projects.

In addition, there are mission trips, which allow young people to feel that they’ve made a difference for others. The Rev. Mary Hudak, recently called to be rector of St. Michael’s in Carmichael, California, points out that it’s important to involve parents in the planning, especially because they know what their kids will and won’t do, and they’re the ones who will get the kids to attend.

“If parents see that their kids are doing meaningless work, they won’t get on board. If it smells like a vacation, they won’t want it. They already go on vacation with their kids.”

This message extends to working with other groups of young people at church. The 25 acolytes at St. Stephen’s are receiving leadership training, Hudak says.

Suggestion # 2: View your diocese as a mega-church

Diocese of California Bishop Marc H. Andrus talks with confirmands at an annual Confirmation Weekend. Photo/CDSP

Diocese of California Bishop Marc H. Andrus suggests that it is important for church leaders to reframe the way they view their resources. Rather than viewing ourselves as small, he suggests: “We are a mega church of 27,000 members, spread over a somewhat larger geographical area that happens to be called the Diocese of California.”

This is his way of describing his introduction of “area ministry” into the diocese, an approach to empower the community. Andrus offers three examples of how those interested in youth ministry can work as the body of Christ in collaboration:

• The Marin Episcopal Youth Group collaborative, with regular Sunday meetings among youth members from five churches. Although from different neighborhoods, the members are bonding under London’s leadership. “None of these congregations could, on their own have a valid, vibrant youth ministry,” Andrus says. “Together, however, they have started a ministry with young people that holds great promise.”

• The God Squad. Formed eight years ago, this group, once highly active, included at times, youth leaders, young adults and deacons sharing confirmation activities and mission trips. The churches that were represented included St. Paul’s in Walnut

Creek, St. Timothy’s in Danville, St. Anselm’s in Lafayette, Church of the Resurrection in Pleasantville and St. George’s Episcopal in Antioch.

• Diocese-sponsored events: The Diocese of California sponsors Confirmation Weekend at St. Dorothy’s, an annual retreat held in March when young people from Episcopal churches throughout the diocese join together for worship and play. Additionally, the diocese sponsors Nightwatch in San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral for middle school and high school students and Happening for high school students.

Brenda Lane Richardson, an author and clinical social worker, uses memoir writing as a therapeutic modality. Her most recent work, “You Should Really Write a Book,” was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2012. She is married to CDSP’s dean and president, the Rev. W. Mark Richardson, PhD. This article is part of a series that first appeared in the Spring 2013 issue of Crossings, an alumni publication of the Church Divinity School of the Pacific.

Social Menu