North Dakota church plans prayer path, traditional garden as environmental reparations for Native Americans displaced 70 years ago by river dam projectPosted Apr 13, 2023 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] Later this spring, after the snow melts and it’s warm enough to plant, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, White Shield, North Dakota, will begin construction of a prayer path to commemorate six Indigenous communities lost to the creation of Lake Sakakawea in 1953. The Missouri River, which runs through the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in western North Dakota, was dammed in a project that ultimately displaced over 1,700 Indigenous people – 80% of those who lived on the reservation – and the loss of the rich farmland they and their ancestors had cultivated for centuries.

The environmental reparations project will include a garden of traditional plants and a series of elder-led talks about the culture of the Arikara tribe in addition to the prayer path. The Diocese of North Dakota received a $52,500 United Thank Offering grant to support it.

The project is meant as reparations for what was lost when the lake was created and supports the Indigenous understanding of making something right, the Rev. Bradley S. Hauff, Indigenous missioner for The Episcopal Church, told Episcopal News Service. While some efforts at reparations are financial, Hauff said Indigenous cultures see other ways to help right the wrongs of the past. “We look at it as restoring the relationship that was put in place by the Great Spirit, by our Creator, and how can that be done? It addresses issues pertaining to the land and care of creation, and restoration of the ecosystem that has been damaged.” Projects like the one at White Shield “are really more of an all-encompassing way of righting the wrongs of the past than just writing a check for it,” he said.

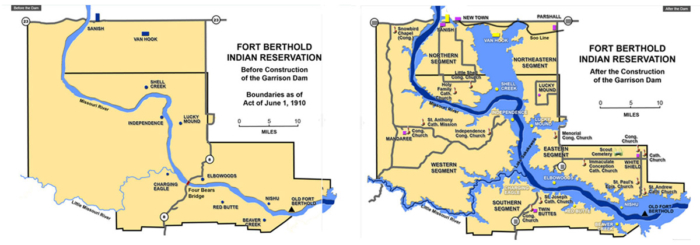

Maps show the original size and shape of the Missouri River (left) as it flowed through the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation and the flooding and lakes that resulted from the construction of the Garrison Dam in 1953 (right). Flood waters covered most of the ancestral homelands of the Arikara people who lived on the reservation. Please click on the image to enlarge it. Images: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “Lake Sakakawea Garrison Dam Boating and Recreation Guide”

The prayer path will take the shape of the Missouri River as it once ran through the reservation. The location of the original Indigenous communities that were lost to the lake each will be marked on the path by a cedar tree and a stone, items that are sacred to the Arikara people. They are one of the three tribes whose members live on the reservation. Signs in both Arikara and English will describe the six towns’ history and stories, Robert Fox, a cultural wellness specialist at the United Tribes Technical College in Bismarck, told ENS. Fox is the son of the Rev. Duane Fox, who leads the congregation and is the diocese’s elder priest.

Robert Fox, a member of the Arikara tribe and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, White Shield, North Dakota, points to the location of a new prayer path to be constructed later this spring. Photo: Kim Becker

Community members had several years while the dam was under construction to prepare for the eventual loss of their homes, Fox said, and many were able to move their houses and other buildings “from below” to higher ground. Among the buildings moved was the original St. Paul’s Church, which burned to the ground in 1955, leaving only its concrete foundation and steps. The new prayer path will begin near the current church building and end near the old steps, Fox said. To the north will be a garden of native plants that for generations sustained the Arikara – corn, beans and squash, which in many Indigenous cultures are called the “Three Sisters” – as well as ceremonial plants including sage, sweetgrass and tobacco. The outline of a traditional earth lodge will be built nearby and will serve as a place for teaching about Arikara agriculture and for prayer, he said.

Three-quarters of a century later, few tribal members recall the time before the land was flooded, Fox said, and as a child, he thought of the lake as a beautiful place for fun and recreation. “But my dad never talked about how beautiful it was,” he said, having been one of those displaced. Even given its size – it’s the third largest man-made lake in the United States – on a quiet evening Fox can detect the sound of moving water. “You can hear the river going through it,” he said.

A place, and a model, for reconciliation

Reconciliation is a top priority for the Diocese of North Dakota, the Rev. Steven Godfrey, diocesan minister, told ENS that, and the prayer path and garden engage that “in some very creative, rather beautiful ways.” He envisions the area as a place of pilgrimage for people inside the diocese and from the wider church, where it not only will tell the truth about what happened in the past but can begin to provide some healing from the trauma that resulted. “It is a positive, constructive and caring approach that values the care of creation that is deep within [Indigenous] culture,” he said.

Six of the diocese’s 19 congregations are located on reservations, and Godfrey said they have an important presence in the diocese, along with Indigenous people who are active in other churches. He said the diocese is intentional about lifting up the role of tribal members, including making certain they are represented in leadership positions.

Hauff noted this project aligns with The Episcopal Church’s emphasis on racial reconciliation, healing and justice through Becoming Beloved Community, but with an expanded understanding. In a webinar that looked at this and two other UTO-funded projects to be featured in upcoming stories, he said that most people understand Beloved Community “as a type of human community or human society that is guided by principles of equity, fairness, equality and inclusion. The Indigenous worldview looks at it in that way, but in a more expansive way. We see ourselves as part of a cosmic relationship that is sacred and involves the universe and certainly our Earth. We see everything and everyone as related.” And that relatedness extends just beyond people. “We have a responsibility to one another as relatives, and so people, yes, but also animals, birds, fish, insects, everything that moves, as well as those things which, to the Western mind, are not living. Things like rocks and mountains and the sky are also our relatives.”

Hauff said that history has shown worldviews that promote human dominance have dangerous results, including colonization, genocide, land theft and even garbage that extends into space. “Our garbage is everywhere, even on the surface of the planet Mars,” he said, noting that rovers and other equipment sent to the planet will be left there. “We haven’t even set foot on Mars, yet, physically, but our garbage has preceded us.”

Beyond the importance of the White Shield environmental reparations project itself, Godfrey said the project can be used as a guide as the diocese begins researching and telling the truth about the impact of Indian boarding schools and the resulting trauma that exists in the diocese’s Indigenous communities. He said that none of the 12 schools that existed in North Dakota – schools that stripped children of their Indian culture and identity after being forcibly removed from their families – are known to have been operated by The Episcopal Church, but they do include schools that were on the Fort Berthold Reservation, according to a report issued in May 2022 by the U.S. Department of the Interior that explores the nature and scope of these schools. The list of schools by state is in one of the report’s appendices.

Most Indigenous people in the Diocese of North Dakota either attended one of these schools or had parents or grandparents who did, Godfrey said. “There certainly are memories of significant trauma in our communities.”

– Melodie Woerman is a freelance writer and the former director of communications for the Episcopal Diocese of Kansas.

Social Menu