Michigan diocese’s ‘Race and Spirituality’ initiative takes a deep dive into ‘redlining’Posted Mar 11, 2022 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] For Episcopalians in the Diocese of Michigan, encompassing southeast and southcentral regions of the state, and including the city of Detroit, the complex work of racial healing is focused more on reckoning with historical geographic segregation than reconciling slavery’s legacy.

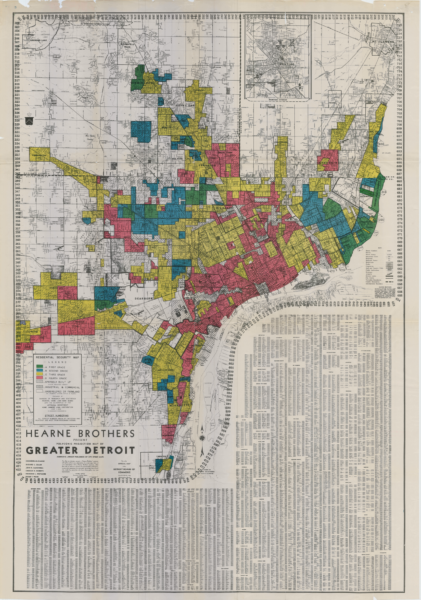

Historical Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Redlining Map for Detroit, Michigan. Credit: Nelson et al. 2020

“Our history in Michigan is less associated with slavery, but more about trying to come to terms with discriminatory practices from over the last century,” said Bishop Bonnie Perry, referring to Detroit’s history of redlining, a still pervasive system of racial bias in housing, financial, medical, city and other services in areas where Black residents lived and rooted in federal policies dating from the 1930s.

Earlier this year, the diocese launched “Spirituality and Race,” a multi-year, multi-faceted anti-racism initiative to study that history, facilitate racial healing and to build Beloved Community, through the lens of spirituality. Previous anti-racism engagement led to the understanding that “how we are shaped and formed in our love for Jesus Christ is going to be the way we look at issues of race and defeat racism in our communities,” Perry said when announcing the initiative.

A recent virtual tour of Detroit, for example, led 30 viewers through an exploration of the city’s complicated, longstanding history of redlining. Detroit was redlined on June 1, 1939. Maps from that time outline the predominantly Black neighborhoods, where real estate mortgages and home insurance were often either denied or unattainable because of price gouging.

A 2021 study ranked Detroit as the nation’s most segregated city with a population over 200,000. The City Institute, a nonprofit agency that educates people about Detroit, designed the virtual tour at Perry’s request.

“One of our short courses meshes with that tour,” said the Rev. Veronica Dunbar, the diocesan missioner for spirituality and race, a position created in 2022. “We were talking about infrastructure planning and urban renewal. It was deliberate and methodical. Literally, from the 1930s onward there has been systemic and structural and deliberate planning that eliminated any kind of generational wealth, that destroyed neighborhoods and moved Black people into overcrowded housing that was substandard. It then gave policymakers the excuse to do ‘slum clearance,’ which destroyed these communities and neighborhoods.”

That urban planners deliberately routed freeways to destroy vibrant Black communities is part of the truth-telling that needs to happen before healing can take place, she said. “We’ve been told a different story of why things are the way they are. We’ve heard, “‘these people didn’t work hard enough, and didn’t care enough about where they live,’” when actually it remains a premeditated structural planning outcome for people of color.

“One of the people in our short course said they had no idea this happened. And then it happened all over the country, and it’s still happening.”

David Laurence, 65, grew up in the 1960s in Dearborn, then a white suburb on Detroit’s west side where, he said, racial dynamics felt oppressive.

“It was so completely white that when the first house went up for sale on the open market, it wasn’t even shown to a Black family, but people came out anyway and put gasoline on the lawn and burned it as a warning. That is my memory of living there,” said Laurence, now a parishioner at St. Clare’s Church in Ann Arbor, about 45 miles west of Detroit.

For Laurence, linking spirituality and race, and educational and relationship-building opportunities, is necessary, “if you’re really going to face the issue of race. It’s hard to do without understanding there’s something larger than me that I can turn to,” he said. “Otherwise, it’s just too much, I can’t face it.”

Bonnie Anderson, former president of the House of Deputies, called the initiative transformative. Since Perry’s 2020 consecration, Anderson has joined diocesan anti-racism efforts such as book and film studies, and facilitated Sacred Ground circles within her congregation, All Saints Church in Pontiac, about 30 miles north of Detroit. Sacred Ground is part of The Episcopal Church’s Becoming Beloved Community, a long-term commitment to racial healing, reconciliation and justice.

“It doesn’t point anybody out. It says we can be this, all of us together,” she said, of Race and Spirituality. “We can be the beloved community and work toward that. It’s taken years to get like this. This is life’s work and it’s not going to be over soon. We’ve got to be in it for the long haul.”

Canon to the Ordinary JoAnn Hardy, a 35-year diocesan staff member who is Black, applauded the initiative as a departure from “the usual check-the-box antiracism program” and from the notion that the work of reconciliation has already been completed.

“This is not reconciliation. There’s been nothing conciliatory thus far. You can’t re-do something you never did,” said Hardy, who said she has encountered “this fear of coming to Detroit” in her ministry across the diocese.

The diocese encompasses 17,000 baptized members and 77 congregations, seven of which are predominantly Black. Demographically, Black residents number 78% of Detroit’s population, and 14% statewide. “But there are communities in our diocese where I have not felt as safe as I do, right here in my cathedral, in my city,” she said.

“We’re actually starting from the beginning,” Hardy said of the initiative. “We’ve actually figured out the link between spirituality and race and how to do some heart changes and how to move people toward loving one another better. I’m really excited. It’s time to move on and to create some real change.”

Perry hopes “to create a movement, bit by bit,” she said. She and Dunbar have led diocesan-wide book and film studies, “Race Matters” short courses and listening sessions to bring Episcopalians together for conversations about race and racism.

Her quest for resources helped inspire Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary’s two-year pilot program, “Anglicanism and Social Justice,” offering theological explorations of racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights, poverty and homelessness, and the environmental crisis, according to Emilee Walker-Cornetta, associate program director.

“Over 90% of participants have some kind of leadership role in their parish and they report they are bringing all they’re learning from the program to bear in their work and communities, which is really exciting,” said Walker-Cornetta. In its second year, the program has about 60 lay and clergy participants nationwide. A third are from Michigan, she said.

Dunbar said virtual worship during the pandemic unexpectedly helped challenge the area’s longstanding geographic separation, creating diocesan-wide relationships and opportunities she aims to extend.

Upcoming events include in-person healing meditations for people of color; a short course about healthcare disparities and a Lenten book study of Ariel Burger’s book, “Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom.”

“It is an incredibly compassionate and insightful book about reaching across barriers, and listening across barriers,” Dunbar said. “Most of all, it’s about being a witness to God’s love and God’s justice in the world.”.

She aims to engage with one another “in a way that makes a more just future possible,” she said. “That just future is not going to be, because we put on rose-colored glasses and felt really good for a while. But, because we persevered in changing and transforming one another, whether one person at a time or a roomful of two hundred at a time. Those little, step-by-step transformations that cause us to move toward actually loving each other, as God loves us, just building the kingdom.”

–The Rev. Pat McCaughan is an ENS correspondent based in Los Angeles, California.

Social Menu