A 300-year-old Episcopal church hopes to connect with spiritual but not religious neighborsPosted Feb 17, 2022 |

|

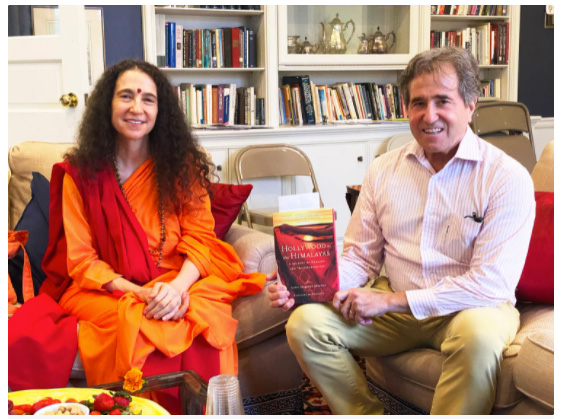

Mark Grayson with Hindu spiritual leader Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati, author of “Hollywood to the Himalayas: A Journey of Healing and Transformation.” Photo: Courtesy of Grayson

[Religion News Service] For three centuries, Trinity Episcopal Church has tried to meet the spiritual needs of the small community of Southport, Connecticut, about an hour and a half outside of New York.

As more and more of the church’s neighbors ditch organized religion but not faith, leaders at Trinity hope a new initiative will help them find meaning and purpose in life even if they never attend a Sunday service.

The church recently launched the Trinity Spiritual Center, which offers lectures, classes on meditation and contemplation, and a sense of community during a trying time, said the Rev. Margaret Hodgkins, the rector of Trinity Church.

“The Christian mandate is to love and serve and I feel like we’re helping people, through this contemplative focus, to be calm and courageous in turbulent times,” she said. “That comes out of time that’s spent in prayer and meditation. So, if we’re helping people to have more contemplative life — that helps everyone.”

Mark Grayson, a former children’s television executive and member of the Trinity church vestry, said the idea for the center grew out of some planning the nearly 300-year-old church was doing as members envisioned their next 100 years of ministry. The group had been working for several years on a strategic plan and realized that while the church could remain healthy, there were needs in the community it was not addressing.

More specifically, they saw people in their community and in the broader culture who were looking for meaning, purpose and balance in life, said Grayson. But those folks were turning to meditation apps or books about wellness and not to the church or other religious institutions.

“There was just this annoying feeling that even if we greatly improved or perfected the model that we now have — it wasn’t going to respond to the trends that we were reading in the broad population and specifically in our community,” he said.

About 3 in 10 Americans claim no religious affiliation, according to data from the Pew Research Center, and a similar number say religion has little influence in their life. Only a third of Americans attend church regularly, according to Pew. But only 4% identify as atheists. And many unaffiliated Americans have spiritual beliefs, according to Pew, even if they eschew organized religion.

Grayson, who has long practiced meditation, wondered if there was a way for the church to create a space where people could gather, connect and share their spiritual journeys, no matter what they believed.

“I’ve been on this huge spiritual journey that has been all over the place, but came back to the church as my anchor,” he said.

The center draws on contemplative practices from the Christian faith and from other traditions, he said, and has hosted programs on spirituality as well as social issues such as racism and gender.

It’s also hosted speakers, including Kimberly Wilson, who performed “A Journey,” her one-woman show about Black women who shaped American history; writer Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati, author of “Hollywood to the Himalayas,” which details her life as a Hindu convert; and the Rev. Matthew Wright, an Episcopal priest and Sufi practitioner who teaches about contemplation. A current series features author Mark Greene, host of the “Remaking Manhood” podcast.

While the center’s ties to the church are clear and its events are held in the Trinity parish hall, there’s no proselytizing or promotion of exclusively Christian beliefs. During its startup phase the center will remain under the umbrella of the church but it is treated like a community service, more akin to the preschool that operates at Trinity than a church program.

About 3 in 10 Americans claim no religious affiliation, according to data from the Pew Research Center, and a similar number say religion has little influence in their life. Only a third of Americans attend church regularly, according to Pew. But only 4% identify as atheists. And many unaffiliated Americans have spiritual beliefs, according to Pew, even if they eschew organized religion.

Grayson, who has long practiced meditation, wondered if there was a way for the church to create a space where people could gather, connect and share their spiritual journeys, no matter what they believed.

“I’ve been on this huge spiritual journey that has been all over the place, but came back to the church as my anchor,” he said.

The center draws on contemplative practices from the Christian faith and from other traditions, he said, and has hosted programs on spirituality as well as social issues such as racism and gender.

It’s also hosted speakers, including Kimberly Wilson, who performed “A Journey,” her one-woman show about Black women who shaped American history; writer Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati, author of “Hollywood to the Himalayas,” which details her life as a Hindu convert; and the Rev. Matthew Wright, an Episcopal priest and Sufi practitioner who teaches about contemplation. A current series features author Mark Greene, host of the “Remaking Manhood” podcast.

While the center’s ties to the church are clear and its events are held in the Trinity parish hall, there’s no proselytizing or promotion of exclusively Christian beliefs. During its startup phase the center will remain under the umbrella of the church but it is treated like a community service, more akin to the preschool that operates at Trinity than a church program.

Linda Mercadante, a former college professor and author of “Belief Without Borders,” a study of Americans who are spiritual but not religious, said that more progressive Christian churches are often more open to adding programs about diverse forms of spirituality. That won’t reverse the decline of organized religion, she said. And she wonders what the Trinity center or similar programs can offer that isn’t already being offered somewhere else.

“I don’t know what they are going to achieve,” she said.

So far, the spiritual center has made some inroads with connecting to the community. About 700 people — most of whom have no ties to the church — have taken part in the center’s programs, said Virginia Cargill, a friend of the church who has helped the center with strategic planning.

The next step, said Cargill, is creating a sustainable financial model. The center has just begun planning some fundraising programs, which show promise, she said. When the center needed to raise money to upgrade the parish hall with video equipment, people responded.

“I swear to God, in less than three weeks, we raised, you know, the money that we needed to have,” she said.

Grayson believes strongly that learning about spirituality in community matters. He said spiritual practices such as meditation are often turned into navel-gazing tools for self-help rather than spiritual resources for changing the world. While spiritual practices have mental health benefits, he said, the center is after something bigger.

“It’s a place where we go to learn these practices so that we can empty out and let the Spirit move through us so that we then can impact the world in a positive way.”

Social Menu