Diocese of Alabama empowers commission to elevate diverse perspectives on racial injusticePosted Feb 10, 2022 |

|

Executive Council members walk slowly through the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, in October 2019. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

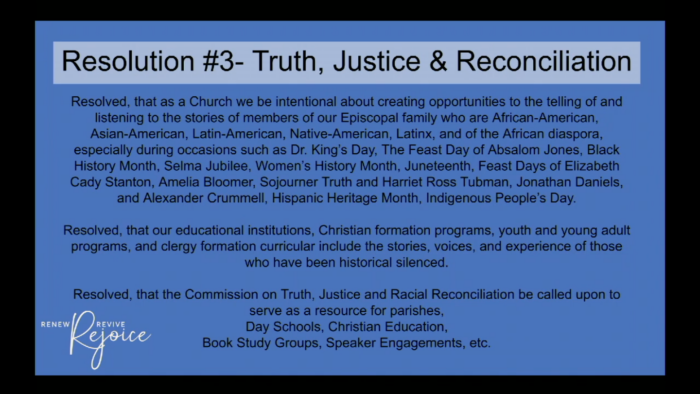

[Episcopal News Service] The Diocese of Alabama passed a resolution this month at its diocesan convention that seeks to bring a greater spirit of truth-telling to its racial reconciliation work by raising up “the stories, voices and experience of those who have been historically silenced.”

The diocese’s action follows a nationwide debate over how the racism and oppression present throughout American history should be taught in taxpayer-funded primary and secondary schools. Alabama is among the states where state and local officials have passed measures prohibiting or restricting the teaching of concepts like critical race theory, an academic approach to examining the traces of racism still manifested in American systems and institutions. Critics of such prohibitions point out that critical race theory typically is discussed in college classes, not in K-12 schools.

The Diocese of Alabama resolution doesn’t mention critical race theory, though its preface laments that “some in positions of power and influence,” acting in fear of the truth about racism, want to “prevent our schools from teaching this history now because it might make our children feel bad or ashamed.” The resolution empowers the diocese’s Commission on Truth, Justice and Racial Reconciliation to serve as a resource for congregations, schools, Christian formation groups and other Episcopal organizations as they invite racially diverse guests to share their stories and perspectives.

“The history that we have been taught is the history that has been brought down to us from the dominant culture, and many times it has very minimal, if any, voices outside of the white culture,” the Rev. Carolyn Foster, a co-chair of the commission, said in a phone interview with Episcopal News Service this week.

“The history that we have been taught is the history that has been brought down to us from the dominant culture, and many times it has very minimal, if any, voices outside of the white culture,” the Rev. Carolyn Foster, a co-chair of the commission, said in a phone interview with Episcopal News Service this week.

Foster, who is Black, serves as a deacon at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, a historically Black congregation in Birmingham. She told ENS she recently was invited to preach a guest sermon at another church in the diocese for Black History Month. The diocesan resolution, proposed by her commission, encourages more of those kinds of interactions across racial differences, especially on holidays and church feast days that have special meaning for people of color, such as Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Juneteenth, Hispanic Heritage Month and Indigenous Peoples Day.

Some Alabama congregations already have been engaged in that kind of work, and the new resolution will allow the commission to “nudge just a little bit more,” Foster said, toward telling the truth about racist systems and the church’s past complicity in those systems. “If any diocese ought to be leading in this particular effort, it ought to be Alabama,” she said.

The state was the site of some of the most entrenched segregationist sentiment in the United States during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, with Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma each being a flashpoint on the path toward eventual passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

A statue depicting enslaved Africans is on display at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo: Douglas Sparks

Today, Alabama has become a frequent destination for racial justice pilgrimages, including one underway this week by a group of Episcopal bishops. Stops in Montgomery often include the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum, with exhibits spanning the full history of racial injustice toward African Americans, and its National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which remembers the hundreds of documented victims of race-based lynchings in the country.

The Diocese of Alabama includes all but the state’s southernmost coastal region, which is part of the Diocese of the Central Gulf Coast. The preface to Alabama’s recently passed resolution on racial reconciliation mentions the death in late December of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who organized the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in his country of South Africa after apartheid.

“Following in his footsteps, we, the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama, are compelled to recognize that the truth of our own history, as a church, as a state, and as a nation, has not been told,” the diocese said. “We were taught our history almost entirely from the viewpoint of a dominant race, with much omitted from the story. The history that we learned in schools omitted the realities of racial injustice on a massive scale, from slavery to lynching, to segregation, to mass incarceration.”

As co-chair of Alabama’s Commission on Truth, Justice and Racial Reconciliation, Foster has led numerous anti-racism trainings and workshops for diocesan and congregation leaders. Truth-telling is always an important component.

“What we always stress in our trainings is to tell the truth, because it is the truth that will set us free,” she said. “The essence is … to speak your truth and to listen to one another.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu