‘My Name Is Pauli Murray’ brings trailblazing Episcopal saint’s story to a wider audiencePosted Sep 28, 2021 |

|

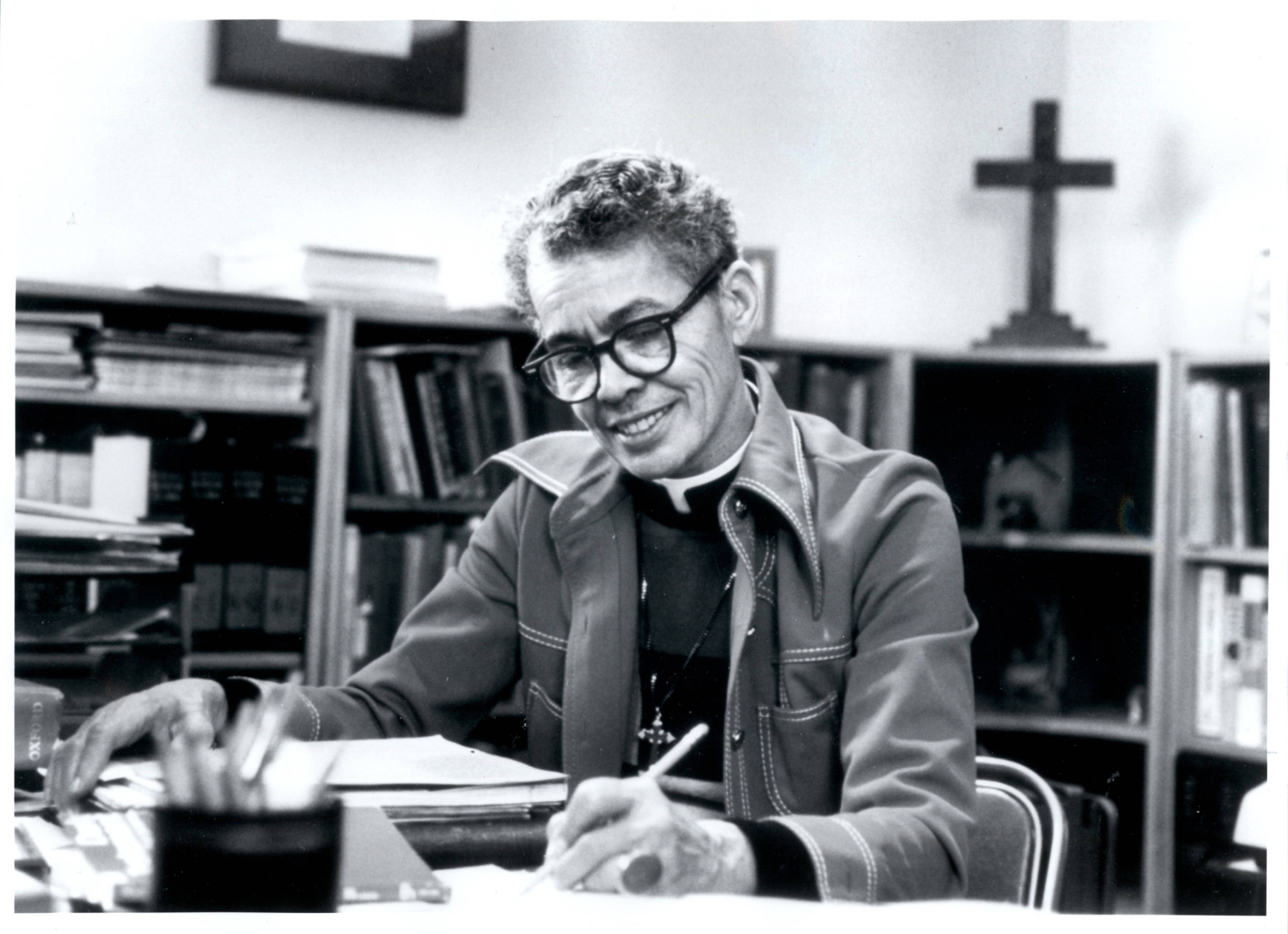

The Rev. Pauli Murray, the first Black woman ordained an Episcopal priest. Photo: Carolina Digital Library and Archives/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

[Episcopal News Service] In the new documentary “My Name Is Pauli Murray,” filmmakers Betsy West and Julie Cohen paint a picture of an unsung trailblazer who remains relatively unknown despite her lasting influence on American society. Episcopalians know her as the first African American woman to be ordained a priest and as a pioneer in the struggles for racial and gender equality. But many may not know about other important aspects of her life, such as her struggle to come to terms with her gender identity in an era long before transgender people were accepted in mainstream society.

When West and Cohen came across Murray’s story while working on their previous film (“RBG,” the Ruth Bader Ginsburg biopic), they wondered why such a pivotal figure wasn’t a household name.

“‘Why didn’t we know this person?’ was the first question everybody asked,” West told Episcopal News Service, “and could we do something about it?”

The result, “My Name Is Pauli Murray,” premiered online in January at the Sundance Film Festival and is now playing in select theaters. Washington National Cathedral will screen the documentary for an in-person audience on Sept. 30. It will stream on Amazon Prime beginning Oct. 1. It will also be shown online the same day through the Church of the Heavenly Rest in New York, followed by a discussion with West and Presiding Bishop Michael Curry. The film, which incorporates excerpts from Murray’s diaries and memoirs, shows how she laid the groundwork for future achievements for racial and gender equality.

Murray is celebrated on July 1 in The Episcopal Church’s “Holy Women, Holy Men” calendar of saints, and an increasing number Episcopal leaders – especially Black and LGBTQ+ people – cite her as an influence. Trinity Church Wall Street and the Diocese of North Carolina are supporting partners of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice at Murray’s childhood home in Durham, North Carolina.

Murray was undaunted by the fact that she was often the first and/or only Black woman in the positions she held. Fifteen years before Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to move out of a whites-only section on a bus, Murray and a friend did the same in Virginia, though their case did not gain momentum the way Parks’ did. In her legal career, she was among the first to argue the unconstitutionality of “separate but equal” laws, an argument cited 10 years later in Brown v. Board of Education by Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, who called her book on segregation laws “the bible of the civil rights movement.” Ginsburg used Murray’s arguments in a brief she wrote – listing her as a co-author – while arguing Reed v. Reed, the 1971 Supreme Court case that banned gender discrimination based on the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Part of what makes Murray significant today was her commitment to intersectionality: the idea that social justice movements for different groups should support each other rather than work alone. As a Black woman experiencing discrimination based on both her race and her gender – a situation she described as “Jane Crow” – Murray supported the civil rights and feminist movements. But intersectionality was not as common then as it is today, and Murray’s penchant for crossing boundaries is one reason she didn’t achieve wider renown, West said.

“The civil rights movement was not as open to acknowledging the contributions of women as it should have been, and the women’s movement was pretty dense at times about recognizing the needs and the contributions of African American women,” West told ENS. “The concept of Jane Crow really is intersectionalism. It’s a brilliant way to express the double bind that African American women find themselves in, and it was certainly true for Pauli.”

Another factor was Murray’s sexuality and gender identity. In her diaries, Murray described having relationships with women but feeling that she was not a lesbian but a man living in a female body. This experience would today be classified as gender dysphoria and might have led Murray to live as a transgender man or a nonbinary person, the film suggests. The film also considers what pronouns should be used to describe Murray, who used she/her pronouns to describe herself, though some today speculate that Murray would have preferred they/them or he/him. In any case, Murray did not have those options in the mid-20th century.

“The difficulty of living a somewhat secret life – the problem of feeling so strongly of having a male identity in what everybody says is a female body and not being able to express that – plus having what would be considered lesbian relationships at a time when that was not accepted as well – may have caused Pauli to be a little bit less up front in taking leadership roles,” West speculates. “It didn’t stop Pauli, certainly, from speaking out, having contact with lots of very powerful, important people, but Pauli didn’t stick around to take the credit for a lot of the ideas.”

The Episcopal Church is one place, West said, where Murray received due recognition.

“A lot of people say, ‘Why didn’t I know about Pauli Murray?’ There are a lot of Episcopalians who know about Pauli Murray,” West told ENS. “The church has been one place that has lifted up Pauli’s name.”

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu