Archdeacon remembered for ministry among Alaska Natives century after his historic ascent of DenaliPosted Jun 7, 2021 |

|

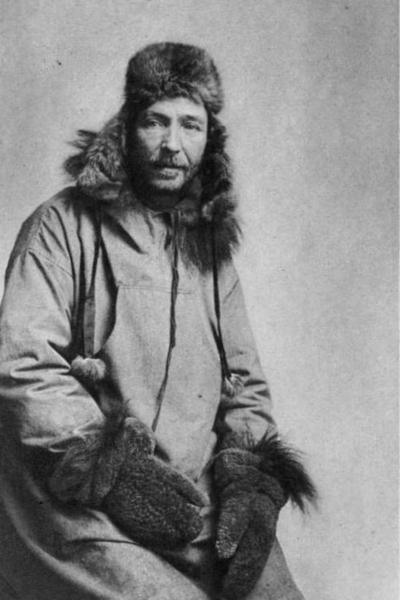

Hudson Stuck is seen with his dog team and a sled with a personalized sled bag hanging from the back, in a photo captioned “Rough Ice on the Yukon” in his 1914 book, “Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled.”

[Episcopal News Service] Hudson Stuck, though his name may be unfamiliar to many Episcopalians, is a legendary figure in the church in Alaska and in mountaineering circles, thanks to his role in organizing a historic expedition on Denali. The Alaska archdeacon, 49, and three companions became the first on record to reach the summit of North America’s highest peak, at 20,310 feet, 108 years ago on June 7, 1913.

Stuck also is remembered for advocating the preservation of Alaska Native culture – he once lamented white cultural incursions as “the steamroller of our civilization” – while expanding The Episcopal Church’s ministry among Indigenous communities.

After moving north in 1904 at the invitation of then-Alaska Bishop Peter Trimble Rowe, Stuck first left his mark in Fairbanks at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, where he created a library and reading room for men as a free-time alternative to the local saloons and brothels. Stuck, who is depicted in one of St. Matthew’s stained-glass windows, also started a mission church in Fairbanks and oversaw the development and opening of an Episcopal hospital.

Hudson Stuck was called to Alaska in 1904 by then-Bishop Peter Trimble Rowe to serve as archdeacon of a mission field spanning 250,000 square miles.

The rest of his mission field spanned 250,000 square miles. His early years traversing that territory would provide the literary material for “Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled,” a book by Stuck that offers a wealth of insight into this larger-than-life figure, Alaska Bishop Mark Lattime said in an interview with Episcopal News Service.

“You discern his genuine love for the people and his genuine love for their culture and identity,” Lattime said. “I think almost universally here in Alaska, he is recognized as having been a positive minister and beloved of the Native community. He certainly did well by Walter Harper.” Harper, the 20-year-old son of an Athabascan mother and Irish father, was the first of the four men in the Denali expedition to reach the summit in 1913.

Patrick Dean was in his 20s when he first learned about Stuck, having picked up Stuck’s book while working in a bookstore in his native Mississippi. “At that time, I was really interested in Africa and Alaska,” Dean told ENS. “I guess I wanted to get out of Mississippi.”

Dean never made it to Alaska himself – the pandemic foiled a planned trip there last year – but he recently published his own book, “A Window to Heaven,” which centers on the planning, preparations and completion of the 1913 Denali expedition. Along the way, Dean highlights Stuck’s childhood in England, his brush with frontier life in Texas, his religious studies at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, and his extensive travels across the vast Alaska Interior to visit the region’s far-flung Episcopal missions.

“Hudson Stuck would always treat the community with which he worked, whether the millworkers of Dallas or the Indigenous people of Alaska, as human beings worthy of respect as equals before God,” Dean writes in an early chapter of his book.

Stuck, while driven to climb Denali by his own sense of adventure, also saw it as a way to promote Native culture, starting with the peak’s name. White prospectors and Americans in the Lower 48 began calling it Mount McKinley as a tribute to the 25th president, and that name stuck after McKinley’s 1901 assassination. But human habitation around the mountain dates back about 15,000 years, with Indigenous peoples for many generations referring to it by a variety of names in their languages, including “Denali,” or “the tall one” in the Koyukon language.

Stuck publicly supported Alaska Natives who advocated preserving the name Denali. In 1917, however, the federal government made Mount McKinley official when it created a national park around the mountain. That name would stand nearly a century, until the Obama administration officially renamed it Denali in 2015.

“A Window to Heaven” by Patrick Dean details the planning, preparations, completion and aftermath of the 1913 ascent of Denali.

Stuck was an alumnus of the School of Theology at the University of the South in Sewanee, where Dean moved in 1999. Dean first began writing about Stuck while earning a master’s degree in theology from the university. At that time, Dean was a ninth-grade history teacher at St. Andrew’s-Sewanee School and wanted to dig deeper into the history of religion. His master’s thesis in 2006 was “The Muscular Christianity of Hudson Stuck.”

The “muscular” movement among late 19th-century missionaries emphasized physical strength, grit and social justice advocacy. Stuck embodied that ethos, Dean said, but he resisted its less noble tendency toward paternalism, condescension and sometimes even racism.

“He was proud to have gone around to all his churches in the dead of winter, in 50-degree-below whiteouts, but he didn’t have the sort of arrogance of the ‘white savior’ complex,” Dean said, adding that Stuck’s attitude generally aligned with that of his church. “The Episcopal Church had a history of being more empathetic and sympathetic to Native cultures and sensibilities than some of the other denominations.”

Stuck’s defense of Alaska Native culture and language, however, did not extend to the spiritual life of the Indigenous peoples he encountered, Dean said. As a missionary archdeacon, one of his ultimate goals was to convert them to Christianity, away from their Native belief systems.

“The missionaries’ presence – even that of someone as open-minded as Stuck – inherently undermined the ancient ways of Alaskan Natives,” Dean writes in his book.

That complicated dynamic has played out in the liturgy of Anglican and Episcopal worship services since the late 18th century, when Anglican Archdeacon Robert McDonald oversaw translations of the Bible, prayer book and hymnal into the Indigenous languages of the Canadian Arctic. Stuck followed suit in Alaska, helping to preserve those languages by promoting Native translations for worship.

Hudson Stuck took this photo of his fellow members of the 1913 Denali expedition. Pictured from left are Robert Tatum, Esaias George, Harry Karstens, John Fredson and Walter Harper.

“The objective was to Christianize, but not necessarily to civilize,” said Allan Hayton, who serves as senior warden at St. Matthew’s in Fairbanks. “Archdeacon McDonald thought that Gwich’in people were already civilized. They didn’t need to be made to act like white people.”

Hayton recalls regularly attending Episcopal services celebrated in the Gwich’in language while he was growing up in Arctic Village. Native or bilingual services are not as common today, further challenging efforts to preserve the language, he told ENS. “Our language is shifting, eroding,” he said.

Hayton, 52, works in the Doyon Foundation’s language revitalization program. Like Stuck’s guide Harper, Hayton comes from mixed ancestry. He is Gwich’in on his mother’s side, and his father’s family was Scottish and Irish. One of his relatives, John Fredson, was part of Stuck’s expedition in 1913 but remained in the basecamp and didn’t make it to the summit. Hayton agreed to advise Dean on his book, to improve its cultural accuracy.

“I was happy to read it, and I really enjoyed learning more about Hudson Stuck and Walter Harper and the ascent itself,” he told ENS.

One of the more interesting subplots, Dean said, was the thorny relationship between Stuck and Harry Karstens, who would later serve as the first superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park in the 1920s. Karstens, a more experienced outdoorsman, resented the focus on Stuck in news coverage of their ascent of Denali, which became known as “Stuck’s expedition.”

“Karstens not only resented that, but he accused Stuck of orchestrating it,” Dean told ENS. That irritation grew while they still were on the mountain and boiled over afterward, though Dean said there was evidence Stuck had tried to correct the record about the group’s shared achievement.

Harper, meanwhile, is revered today in Alaska, especially among Indigenous communities, as an important historical figure, Lattime said. He was “able to bring together the two cultures he lived within,” but sadly he died in 1918 in a shipwreck at age 25. Last year, Alaska celebrated its first Walter Harper Day on June 7, marking the day he first reached the summit, and a fundraising drive aims to create a statue honoring him.

Descendants of Stuck’s expedition team participated in a centennial climb to the top of Denali in 2013. Lattime had planned to represent Robert Tatum, a 21-year-old seminarian who was one of the original four until one of Tatum’s relatives signed on and Lattime gladly gave up his spot. The bishop continued to serve as chaplain to the centennial team.

Stuck’s adventurousness isn’t necessarily emblematic of clergy who serve today in the Diocese of Alaska, Lattime told ENS, though “it certainly is expected if you’re going to serve in this diocese, particularly in our more rural communities, that you are prepared to live the lifestyle that you will be encountering in that community.”

“And for some, that lifestyle would be a big adventure. … To an Indigenous person in Alaska, they would describe it as a Tuesday.”

With Stuck as one model, today’s clergy, Lattime said, must be “willing to come in and be open and understand that they’re not bringing the Gospel to this place, they’re coming to discover how the Gospel is already there.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu