Localized ordination programs open doors to ministry for nontraditional clergy candidatesPosted May 11, 2021 |

|

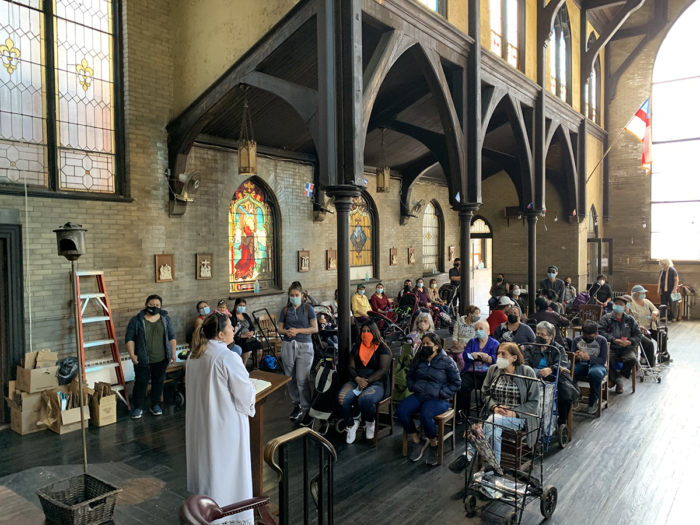

The Rev. Yesenia Alejandro, the Diocese of Pennsylvania’s Hispanic missioner and vicar of Philadelphia’s Church of the Crucifixion, addresses worshippers before a Tuesday food distribution. The church, which was shuttered before Alejandro took over, provides food to some 1,000 people weekly. Photo: Courtesy of Yesenia Alejandro

[Episcopal News Service] Six months after making history as the first Latina ordained as a priest in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania, the Rev. Yesenia Alejandro is now feeding an average of 1,000 people a week at a South Philadelphia church that until recently had been shuttered.

“When I got ordained a priest, the bishop said to me, ‘We’re going to appoint you as Hispanic missioner,’” Alejandro told Episcopal News Service recently. “Right after that, they told me about this church that was closed and said, ‘Go there and reopen it.’ I said OK.”

Alejandro, 49, a mother of four and grandmother, has worked for 25 years with the poor in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Puerto Rico — where she was born. She was ordained as a priest on Oct. 10, 2020, through a local formation program specifically designed for her and implemented by Pennsylvania Bishop Daniel Gutiérrez. She now serves as both the diocese’s Hispanic missioner and vicar of Church of the Crucifixion in Philadelphia.

“Yesenia had this background, she was already working with the poor,” Gutiérrez said. “She has got the biggest heart and the greatest love for Jesus Christ. Why should there be this barrier [to ordained ministry], this wall that does not allow her to use that voice and to proclaim the good news?”

Increasingly, dioceses are turning to local programs and Anglican partners to train leaders who feel called to ordained ministry and for whom ordination might not otherwise be an option, whether that’s due to time or financial constraints or family commitments.

The Rev. Yesenia Alejandro, wearing the purple mask, was ordained a priest in October 2020 through a local ordination program in the Diocese of Pennsylvania. She is the diocese’s Hispanic missioner and vicar of the Church of the Crucifixion in Philadelphia. Photo: Courtesy of Yesenia Alejandro

“It can be used for anyone,” Gutiérrez said. “Who says there’s not people in the Diocese of West Virginia or Lexington that have the same obstacles? All you have to do is have the willingness and the heart. There’s something special about being ordained in the community, knowing its culture, knowing the language, but you know … heart speaks to heart, and what better way to be evangelists?”

The Episcopal Church’s Office of Asiamerica Ministries through its Karen Episcopal Ministry Formation Team and the Southeast Asian Convocation, launched a program in March to train about 20 members of the Karen community as catechists, deacons and priests. “Some 30 congregations or groups of Karen immigrants and refugees have joined The Episcopal Church in the past five years,” according to the Rev. Fred Vergara, the church’s missioner for Asiamerica Ministries.

Cherry Say was 7 years old when her family fled their Myanmar home because of ethnic and religious persecution of the Karen people, the country’s second-largest ethnic minority. She spent the next 20 years in the Mae La refugee camp in Thailand, where she taught Sunday school to youth and young adults.

Now a mother and grandmother, Say, 48, lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and hopes to follow in her father’s footsteps and become a priest. She serves as a lay Eucharistic visitor at Messiah Episcopal Church, where about one-half of the 350-member congregation are Karen and regard her as a pastor.

Cherry Say, standing near the door, serves as a lay Eucharistic visitor at Messiah Episcopal Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, she’s on track to be ordained through the Episcopal Church in Minnesota’s School for Formation. Photo: Courtesy of Cherry Say

“When I came, they did not have a leader, a pastor” who spoke or understood the S’gaw Karen language, Say told ENS. “A lot of my people here did not understand this very well. They are very sad. They feel like they have to be baptized all over again.”

Localized ordination is a win-win, church leaders say, allowing individuals to answer the call to ordained ministry, sometimes in direct response to community needs and shifting demographics and at times in response to congregations that might not otherwise be able to call a priest.

There are places in the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey “where I could put three or four congregations together and they’d still not be able to afford a full-time seminary-trained priest,” Bishop Chip Stokes told ENS.

Since his November 2013 consecration, Stokes has prioritized creating “entry points for growing ministry,” including expanding an existing diocesan School for Ministry. For Stokes, it is also a matter of simple math: “We have 138 congregations and 80 full-time priests. We were not attracting young people to ministry, in part because it [the ordination process] was burdensome.”

Such local programs “are nothing new,” according to Sandra Montes, who designed Alejandro’s three-year course of study. Adhering to Title III, Canon 8 requirements concerning the ordination of priests, local programs include an emphasis on preaching, theology, ethics, pastoral care, Scripture, church history, liturgy and music, Anglicanism, spirituality and ministry practice in contemporary society.

Contextualizing training “is so important for The Episcopal Church. The current system just isn’t built for everybody,” said Montes, dean of chapel for Union Theological Seminary and an educator, writer and speaker. For example, for many prospective clergy, leaving family or employment to attend a three-year residential seminary is not an option.

“Honestly, this way is more biblical,” Montes added. “Walking beside someone, tailoring the knowledge of Jesus with one person in mind, that’s how the disciples were formed.”

In the Diocese of Hawaii, the Rev. Ha’aheo Guanson, 69, deferred her dream of the priesthood while raising a family and establishing a university teaching career.

When the diocese created the Waiolaihui’ia, or Gathering of the Waters, local formation program in partnership with the Austin, Texas-based Seminary of the Southwest’s Iona Collaborative in 2013, Guanson’s dream revived. “I felt ordination was possible to achieve,” she said.

Guanson, ordained in 2019, now directs and teaches coursework in the Waiolaihui’ia certificate program, which includes online and in-person graduate-level studies that can be completed over three to 12 years.

“I have become very passionate about this type of program,” Guanson told ENS. “Here in Hawaii, we’ve always imported priests because we didn’t have our own. There were a few who could go away to residential seminary, but the cost and the time and the loss to the community was always an issue. Having the program right here, you help to raise deacons and priests from your community … reflecting the kind of diversity that reflects the people of God.”

That diversity also includes bivocational clergy for churches “now unable to call full-time priests,” ultimately strengthening the entire diocese because of the program’s potential to include training for the laity, she said.

Local formation is an important part of the church’s future, if the church aspires to expand its base, says the Rev. Nandra Perry, who is herself a bivocational priest, serving as assistant director of the Iona Collaborative and vicar of St. Philip’s Church in Hearne, a town of about 4,000 inhabitants located northeast of Austin.

“We simply need to have more tools in our toolkit for educating clergy if we want our clergy to reflect the diversity of the church itself,” said Perry, who graduated from the Diocese of Texas’ Iona School for Ministry. “People have all kinds of different situations. We want to be able to call people into ministry from all walks of life and be open to the gifts of all of the people who are drawn into this communion.”

Yet, local training should not — and she predicts will not — replace the traditional three-year residential seminary training. “It’s simply one of many possible ways we should be open to preparing people for ministry.”

The Iona Collaborative currently partners with 32 dioceses with about 200 students enrolled across the church each year. The Iona Collaborative is planning to provide teaching materials in Spanish in the near future, said the Rev. John Lewis, the collaborative’s director and lecturer in New Testament and spirituality. In partnership with the Diocese of Los Angeles, some of the Iona Collaborative instructional videos have been translated from English into Mandarin and Korean.

For Daphne Roberts, 63, a lifelong member of St. Augustine’s Church in Asbury Park, New Jersey, is working toward ordination as a permanent deacon. For Roberts and her fellow students at the New Jersey School for Ministry, graduation represents mastery not only coursework comprehension but also cultural competency.

For example, students are required to contextualize the way they would proclaim the Gospel for specific audiences, according to the Rev. Genevieve Bishop, who directs the program. “What is the message they’re giving to this particular audience? It is intended to allow them to really synthesize and pull together everything that they have learned and think about how to apply it in the world today.”

Congregations typically look for clergy who are a good fit for their culture, says the Rev. Susan Daughtry, missioner for formation for the Episcopal Church in Minnesota. With about 25 students, its School for Formation partners with the Church Divinity School of the Pacific’s Center for Anglican Learning and Leadership and Bexley Seabury Seminary, as well as specially designed programs such as the partnership with the church’s Office of Asiamerica Ministries and the Anglican Church Province of Myanmar.

Local formation follows an early church model from a time before residential seminaries existed, Daughtry said. “I will be so happy when nobody talks about this as ‘alternative’ training because it sounds like we have to make special accommodations. We are trying to create a space where the full diversity of the church is well and thriving.”

The approach also empowers congregations. “We’ve tried to allow congregations to be much more creative about their own ministry models, to see what God is doing and not be constantly burdened by financial challenges they can’t meet,” she said. “We are stepping into what it really means to believe in the ministry of all the baptized.”

For example, Daughtry said, “if a congregation has lost membership and can no longer afford to pay a rector, some might think the congregation has come to the end of their existence; but that’s not true. They could choose to embrace a different model of leadership that allows resources to flow in a different way.”

The Rev. Judy DesHarnais, who serves as a deacon at Messiah Church in St. Paul, recalled, “The Karen people reached out to us in 2007, asking about Anglican churches. Then they started coming. People say, ‘Isn’t this wonderful, you reached out to them?’ And I reply, ‘No, you got the direction wrong.’”

DesHarnais said the close-knit community — both locally and across the United States — have discerned Say as a pastor, even though women are not ordained in the Anglican Church in Myanmar.

“Many remember her teaching them Sunday school during their camp experience,” DesHarnais said. Say, who has learned English, has demonstrated great leadership, serving on the church vestry and the rector search committee, and is an invaluable resource during home visits to parishioners.

“I’ve been working with the Karen people since 2008, and I still don’t speak or read their language,” DesHarnais said. “I have done some visits where I’ve brought a Karen interpreter, and that’s better than my just doing it on my own. But, sometimes people need to talk about things that are very personal, and having somebody along doing interpretation just isn’t a good thing. To serve the older Karen in the community, you have to be fluent.”

Say’s shared experience with parishioners is especially crucial now, as tensions in Myanmar continue to flare, with demonstrators protesting a February 2021 military coup. Recently, leaders of nine Southeast Asian countries called for an immediate end to the violence.

“Right now, they are not just worried about friends in Myanmar,” DesHarnais said. “The older Karen, who had to run from their villages when attacked by the Burmese military, are being re-traumatized by current attacks on Karen villages.”

Say, who hopes to be ordained as a priest in 2023, said she loves “to pray the psalms and sing together on pastoral visits. I am very happy to take care of my people, and to be a priest.”

– The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a priest in the Diocese of Los Angeles and a longtime ENS correspondent.

Social Menu