Episcopal Church releases racial audit of leadership, citing nine patterns of racism in church culturePosted Apr 19, 2021 |

|

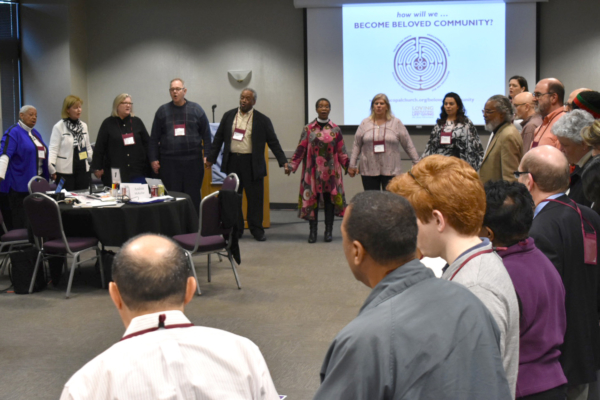

Members of Executive Council join hands and sing at the conclusion of a racial reconciliation training Oct. 17, 2018, in Chaska, Minnesota. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] The Episcopal Church publicly released a report on April 19 that assesses the racial makeup and perceptions of a broad sampling of the church’s leadership and summarizes how race influences internal church culture. The release of the 72-page report, nearly three years in the making, also sheds light on nine dominant patterns of racism that were identified during interviews with dozens of church leaders.

The audit confirmed that the church’s leadership, like its membership, is overwhelmingly white, and it found that white leaders and leaders of color tend to perceive discrimination differently. People of color said they have often felt marginalized – despite the church’s professed commitment to racial reconciliation. White Episcopalians, on the other hand, frequently weren’t aware of how race has shaped their lives and their church.

The Racial Justice Audit of Episcopal Leadership was conducted on behalf of the church by the Massachusetts-based Mission Institute. More than 1,300 people completed a written survey offered to five leadership groups: the House of Bishops, the House of Deputies, Executive Council, churchwide staff members and leaders from 28 dioceses. Additional narrative interviews were conducted with 64 participants who had expressed a willingness to share personal stories and observations with the institute’s researchers.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]A summary of the report is available here, and the full report can be found here. Additional resources are posted to the church’s website.[/perfectpullquote]

“This racial audit has attempted to magnify the voices of people of color in the church, while also maintaining a spotlight on the systems and structures created and maintained by the white dominant culture,” the Mission Institute said in unveiling its findings. By putting those findings into their historical context, the institute concluded that “even though we have come far in addressing racism within the church, we still have a long way to go.”

Episcopal leaders see the audit as part of the church’s efforts to become more inclusive and to bridge racial divides in an increasingly diverse America. Since 2017, those efforts have centered on Becoming Beloved Community, the church’s cornerstone racial reconciliation initiative. It aims to deepen conversations about the church’s historic complicity with slavery, segregation and other racist systems while enlisting all Episcopalians in the work of racial healing. One of its four components is telling the truth about churches and race.

“This racial justice audit, I think for the first time, has given us a real picture of the dynamics and the reality of structural and institutional racism among us,” Presiding Bishop Michael Curry said in a press release announcing the report. “It has given us a baseline of where we are, to help us understand where we can, and must, by God’s grace, go.”

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry leads an Episcopal Relief & Development reconciliation pilgrimage to Ghana in January 2017. Photo: Lynette Wilson/Episcopal News Service

The report offers eight general recommendations for the church as it continues to engage at the parish and community level, from prioritizing racial justice to providing financial support to communities still dealing with the effects of racial oppression. It recommends conducting follow-up audits of church leadership every five years, as well as expanding the audits to dioceses and congregations. It calls for a new system of accountability, ensuring the church steps up its racial justice work. And it cites the need to educate white Episcopalians about the church’s racial dynamics, including through promotion of the audit’s results.

The results were first unveiled earlier this year to each participating group, starting with an Executive Council committee in January. About 200 diocesan leaders attended three online discussions of the results in March, and the Mission Institute presented the report to the House of Bishops on March 12 at the bishops’ online retreat. Similar online sessions were offered to the churchwide staff on March 23 and the House of Deputies on April 15.

Along with releasing the report to the wider church on April 19, Episcopal leaders have prepared resources to help all Episcopalians understand the significance of the audit’s findings while discerning how they can be a part of the church’s continued efforts to combat systemic racism. Three webinars will be offered, on May 11, June 1 and June 29.

“Racism exists in our church, and we can no longer ignore it or look the other way or pretend that it’s not there,” the Rev. Isaiah Shaneequa Brokenleg, the church’s racial reconciliation officer, told ENS. “My hope is that we would recognize the racism in our church and change it.”

The survey questions revealed a disconnect between how white church leaders experience race and racism and how it is experienced by leaders who are Black, Latino, Native American and Asian American and other people of color. When asked, for example, how often they had witnessed less respectful treatment of a person of color, nearly 40% of the leaders of color surveyed responded occasionally or frequently. Only 25% of white respondents shared that view.

“Some of the more striking data that we received back was in how one experiences and observes racism, where there was a significant gap,” the Rev. Katie Ernst, co-director of the Mission Institute, told ENS. Ernst hopes such examples in the report will help Episcopalians better understand white supremacy’s often imperceptible influence on the church.

The Rev. Stephanie Spellers, canon to the presiding bishop for evangelism, reconciliation and creation care, thinks the report’s merits will be evident to anyone who engages with it.

“It’s such a relief to name and see clearly how systemic racism affects power and life in our church,” Spellers told ENS in an emailed statement. “I compare it to a poltergeist – this demonic force that’s been wreaking havoc in a house but nobody can see it. The insights in this report are like throwing powder on the poltergeist. Systemic racism is not a mystery, and it’s not in our heads. Now that we can see it this clearly, we can work more effectively to break free of it.”

The Rev. Gay Clark Jennings, House of Deputies president, told ENS in an interview that the report’s nine dominant patterns of systemic racism are particularly helpful. These examples are “something that we all have to dig into and look at really carefully in terms of how we are structured, how we are resourced and how we invite new people in positions of leadership.”

The report devotes 20 pages to detailing the nine patterns, each illustrated with quotes from people of color and white leaders who were interviewed after completing the survey. Their names were withheld for the report.

A primary pattern was the tension experienced by people of color who feel both invisible and “hyper-visible” in the church. A churchwide leader, identified in the report as a person of color, described feeling invisible while in a room with white bishops: “I’m standing there. But they’re talking, they’re not even making eye contact with me. I’m just kind of right there.”

“Hyper-visibility” was described as a kind of tokenism, when people of color are singled out because of their race, such as to serve on race-related committees or to fulfill diversity requirements.

“I don’t feel like clergy. I feel like a commodity,” one Black priest said. “I’m on these leadership groups so I can check a box, or the leaders can check a box.”

The Community Choir performs at the Communion Service of Lament, Reconciliation and Commitment at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Abingdon, Virginia, during the Pilgrimage for Racial Justice in August 2019. Photo: Egan Millard/Episcopal News Service

Other patterns cited by the report include racial power imbalances in the church, the often hidden complexity and variety of racism, theological practices that can undercut anti-racism work, doubts about the church’s commitment to the work and a lack of understanding of how racism is rooted in the church’s history. The Mission Institute also collected stories that pointed to white church leaders’ propensity to see anti-racism as transactional – a need to improve hiring practices, for example – rather than transformational.

Such analysis was enlightening, Jennings told ENS, and “some of it is bound to make us uncomfortable.” She added that the dozens of first-person examples that were compiled for the report “highlighted the difficulty of navigating an institution that’s predominantly white.”

House of Deputies Vice President Byron Rushing, the most prominent Black lay leader in The Episcopal Church, thinks the Racial Justice Audit of Episcopal Leadership should be required reading for any Episcopal nominating committee. “I don’t think that anybody in leadership who is in the position where they can appoint people or hire people … should do that without reading this report,” he told ENS.

The church also would benefit from a more comprehensive census of churchwide membership, Rushing said. This audit provides only a snapshot of church leadership, but in his view, it is a groundbreaking tool for understanding institutional racism in the church. “I think it’s the first time that we are able to say, this is what a significant part of the leadership of The Episcopal Church thinks about race, all in one spot,” he said.

Its greatest value, he said, may be as a catalyst for further conversations about the church’s racial reconciliation efforts. “We want as many Episcopalians talking about this report as possible,” he said. “The way you keep this in focus is you get people to keep talking about it, in every different way you can.”

The Very Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union in New York, cautioned in an interview with ENS that the lessons learned from the audit must go beyond the need to expand representation of people of color in leadership roles. She advocates a more transformational change in Episcopal Church culture, away from what Douglas calls the “white gaze, that white way of receiving reality.”

“It’s about more than representation,” she said. “That’s not changing the gaze and that’s not changing the controlling narrative of the church.” The potential ramifications are significant, with nonwhite U.S. residents forecast to outnumber whites by 2045. Without transforming its racial attitudes and priorities, Douglas said, the church will remain unable to embody and serve the communities it is called to serve, fueling an existential crisis.

“Inasmuch as our denomination remains a 90% or so white denomination, this conversation’s going to be moot,” she said. The church is “not going to survive.”

The Mission Institute works in the Episcopal tradition to help churches and communities confront racism. It previously helped the Diocese of Massachusetts develop a more inclusive clergy formation process, and it first began interviewing bishops and clergy of color on behalf of The Episcopal Church at the 79th General Convention in 2018.

General Convention has grappled with issues of racism and discrimination for decades, and much of its reconciliation work today is rooted in actions of the 70th General Convention, held in 1991 in Phoenix, Arizona. The church initially faced a backlash for meeting that year in a state where voters had recently rejected a holiday honoring Martin Luther King Jr. The Arizona controversy compelled the church to commit to a long-term examination of its own racism, and it produced an audit of General Convention membership that found a “clear pattern of institutional racism” in the church.

Subsequent measures have broadened and deepened the work, with dioceses offering anti-racism trainings and, more recently, congregations conducting research into the role of slavery and racism in their own histories.

General Convention amplified the church’s commitment in 2015 when it declared racial reconciliation as one of the church’s top priorities, along with evangelism and care of creation. That mandate prompted the development of the Becoming Beloved Community framework.

Another resolution called on the church to address systemic racism and to conduct an internal audit, “to assess to what extent, if at all, racial disparities and systemic racial injustices exist within the Church.”

Jennings, who attended her first General Convention in 1991, said the church doesn’t always move fast, but it has made progress in recent years, particularly last year in joining protests against police brutality and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. The new audit will help the church maintain that momentum, she said.

One of the ways the church can address structural racism, including within the church, is through the actions of General Convention, which sets church policy, approves budget priorities and raises up new leaders, she said. A more diverse mix of bishops and deputies will help broaden the perspectives that inform such decisions. Jennings said she has responded to the report by accelerating her efforts to appoint people of color, especially younger Episcopalians, to key positions on legislative committees in preparation for the 80th General Convention, which will meet in July 2022 in Baltimore, Maryland.

“What I’m hopeful for this time is a much more comprehensive awareness within the church that, not only is our society facing a racial reckoning, but our church is as well,” Jennings said. “We need to seize the moment. We need to take this on.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu