Fewer women in high-profile, high-paying positions partly explains the persistent clergy gender pay gapPosted Mar 24, 2021 |

|

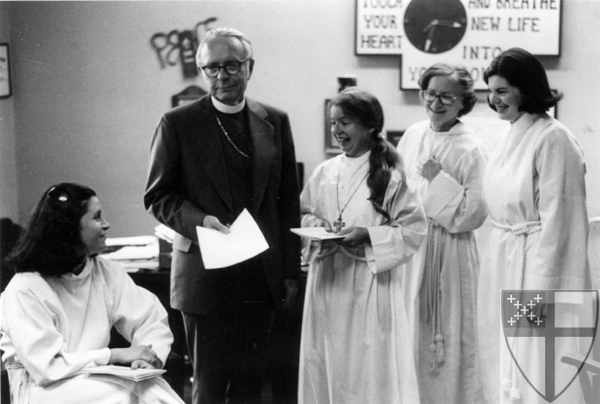

Conferring before an ordination service in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 7, 1975, are (left to right) the Rev. Lee McGee, Bishop George W. Barrett, the Rev. Alison Palmer, the Rev. Diane Tickell, and the Rev. Betty Rosenberg. Photo: Carolyn Aniba/Diocesan Press Service via the Archives of The Episcopal Church

[Episcopal News Service] In 2001, when the Church Pension Group first started publishing differences in average compensation between male and female full-time Episcopal clergy, men earned 18% more than women. Five years later, CPG, the financial services corporation that also tracks clergy demographics, reported that the clergy gender pay gap had only narrowed by half a percentage point, to 17.5%.

“Hence the progress towards compensation equity is slow,” the 2006 report concluded.

Nearly 20 years after CPG published its first report, the gender pay gap has inched closer to parity. The median compensation for male clergy is now 13.5% higher than it is for female clergy, according to the most recent report.

The primary factor in the lingering clergy gender pay gap is the imbalance of women in higher-paying senior positions, according to the data and the observations of diocesan leaders who say it’s one of the areas they’re targeting as they work to close the gap.

“If you look at it from a simple mathematical standpoint,” the Rev. Mary Brennan Thorpe, canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Virginia, told Episcopal News Service, “the biggest lifter of average compensation, the fastest way to get there, would be for female clergy to be called to large churches, to be rectors of large churches which compensate more highly. And yet, there’s still some resistance on the part of some parishes.”

The 2019 report covers 5,344 clergy members, 4,677 of them in full-time positions, in the domestic dioceses (those within the 50 states and the District of Columbia). The report separately covers 248 clergy members in United States territories and other countries. The current makeup of domestic clergy is 60% men, 40% women. The vast majority are priests; 1% of male clergy are deacons, while 4% of women are. Bishops’ salaries were not reported.

While previous annual reports broke down compensation by gender and province, the 2019 report also breaks it down by gender and diocese (for domestic dioceses).

The 2019 median compensation for all domestic clergy was $76,734; for men, it was $80,994, while for women it was $70,772.

Like the clergy pay gap, the gender pay gap among all American workers has narrowed over time, but it persists. In 2019, the median pay for women working full time in the United States was 18.5% less than it was for male workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Sexism remains a major factor and often manifests in unconscious or implicit bias that favors men over women in hiring and compensation levels. Women also occupy fewer high-paying positions than men in most industries, further widening the gender pay gap.

“The wage gap, which exists in our larger culture and in our church, points, to me, to a place of real brokenness in how we value the work of women,” said the Rev. Elizabeth Easton, canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Nebraska.

The Episcopal Church has identified closing the clergy gender pay gap as a priority and has devoted resources to that end for over a decade. In 2009, the church, Executive Council and the Church Pension Fund commissioned “Called to Serve,” an extensive report on the differences in compensation and vocational well-being between male and female clergy. In 2018, General Convention passed a resolution that removed references to gender and current compensation from clergy files in The Episcopal Church’s Office of Transition Ministry – which facilitates clergy searches and calls – as a way to ameliorate discrimination in the first phase of search processes, when parishes are just beginning to browse for a priest with the right qualifications. Another resolution passed that same year, D016, established a task force to examine sexism in the church, including its effect on clergy compensation.

From the report

Since 2000, median compensation (which includes salary, housing and employer retirement contributions) for clergy has steadily increased, though it has remained flat when adjusted for inflation. While previous reports included breakdowns of full- and part-time clergy, the 2019 report does not make those distinctions because the definitions of full- and part-time work vary significantly by region, Curt Ritter, senior vice president and head of corporate communications at CPG, told ENS.

Building on churchwide studies and legislation, some dioceses have initiated local efforts to close the gender pay gap, including identifying points in the search and hiring process that are vulnerable to discrepancies and establishing clarity, transparency and consistency – and then following up with congregations to ensure female clergy are paid the same as their male counterparts.

“I think these things are making a difference in our church, and we’re seeing it. … It’s just agonizingly slow,” said Georgia Bishop Frank Logue, one of three diocesan leaders interviewed for this story.

Another reason the clergy gender pay gap persists rests with women themselves and the positions they apply for. Women tend to underestimate their own abilities and qualifications, compared to men, Thorpe has observed.

“There’s a sense, I think, among some female clergy, and this is something that’s pretty well documented in the literature, that women will assume that they don’t have the gifts to do the job, so they don’t apply for those kinds of [higher-paid] positions,” Thorpe told ENS. “And men will apply for them even if they know they don’t have the skill set. And those of us who work as women clergy and with women clergy are continually encouraging people, ‘Stretch beyond what you think you can do because you probably have the gifts. They just are not as patently obvious to you as they really are.’”

The makeup of parish vestries and search committees that make hiring decisions can also introduce bias. Although women have served as Episcopal priests since 1974, many people who serve on vestries and search committees grew up in a time when female priests were rare.

“What we see often is that the folks at the parish level who have the greatest influence on compensation level and on who gets selected for what kind of position tend to be, shall we say, the more senior members, who have a particular cultural and historical angle of view,” Thorpe said.

It’s a phenomenon dating back almost a half-century that Logue has noticed as well.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Interactive timeline of the history of women’s ordination[/perfectpullquote]

“I do believe that probably all churches, but certainly The Episcopal Church, has an ingrained model of what a priest looks like, and that model is male,” he said, adding that dioceses should make sure search committees are seeking out and interviewing female candidates. While no search committee would explicitly seek a male rector, some members’ implicit bias may limit whom they call for an interview. One way to address this is to have a gender-blind application, in which the committee initially reviews applications without knowing the gender of the applicant.

“If a church is not considering women candidates, they are missing out on what God may be trying to do in our midst,” Logue said.

Male clergy are more likely than female clergy to serve larger, wealthier congregations and hold higher positions to begin with. Parishes with annual operating revenues of over $350,000 are served by 1,329 men but only 780 women. Even when comparing clergy who work in similar roles or comparably sized congregations, or who have the same amount of experience, men still earn more across the board, according to the 2019 CPG report.

Those larger parishes tend to have less turnover in senior positions, which means fewer opportunities for women to advance, Logue said. And since there are relatively few of them – 4% of Episcopal churches have an average Sunday attendance of 300 or more – that influences the overall trend.

“When you get up to a $750,000 or $1 million [parish] budget, all the priests who are serving as rectors [in the Diocese of Georgia] are men, still, largely because of longevity,” he said. “We have churches that I think would call a female priest, no problem … but we just haven’t had a call there yet. That’s the agonizingly slow part that can’t be changed by policy alone. And it’s frustrating.”

And while men who have advanced over long careers to senior positions in large churches have markedly high compensation packages, women often encounter a glass ceiling as their careers progress, said Easton, the canon to the ordinary in Nebraska.

“For entry-level positions like curacy and first-time associate positions where you set the experience meter down lower, people are more likely to set a [salary] and stick to it. It’s over time in our ministries that the experience of men and women is valued differently,” she told ENS.

One factor is the “motherhood wage penalty.” As shown in studies cited by the “Called to Serve” report, women who are working while raising children are paid less than childless women, while men raising children earn more than childless men.

“Research demonstrates that this is at least partly due to discrimination against mothers among employers,” the report states. “Studies demonstrate that this is because the birth of a child creates a more unequal gender division of labor, freeing up fathers to spend more time at work, as well as cultural expectations regarding masculinity and breadwinning that cause employers to prefer fathers to men without children.”

One way to address this, Easton said, is having solid parental leave policies guaranteed from the outset. That way, women are less likely to feel they have to choose between having children and taking a job.

“If you’re in the Church Pension Fund, you have a great parental leave benefit, and I would like to see every parish just have that automatically incorporated into every letter of agreement,” she said. “And that’s one way that you can preserve full-time employment [for women] in a way that you might not be able to do otherwise.”

Easton also identified salary negotiation as a crucial point in addressing the pay gap.

“We’ve learned through studies in the secular world that compensation negotiation is a lot of where this wage gap comes from. And that negotiation is just a bias minefield. How we negotiate as women, and also how our negotiation is interpreted by people – it’s sort of a lose-lose situation.”

Her solution: a diocesan policy that sets a compensation package for every position as soon as the position is posted. By setting that standard from the beginning, “we tend to have more equitable compensation across our diocese for a full-time position,” Easton said.

Using specific, objective figures – “the language of commerce” – with search committees helps ground them in determining appropriate compensation ranges, Thorpe, the canon to the ordinary in Virginia, added.

It’s important “to give search committees clarity about, if you will, what the marketplace is right now,” she said. “That for a position for a church in this diocese, with this Sunday attendance, this revenue level, this is what people are getting paid for those positions.”

While the hiring process is determined more at the parish level, proactive diocesan policies can push churches toward equitable pay. When he was canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Georgia, Logue made closing the gap a priority, along with then-Bishop Scott Benhase. The diocese started by updating the outdated minimum compensation for full-time priests, replacing it with a system that increased compensation with congregational size and years of experience. It later specified how to apply these minimums to clergy who worked part time.

The diocese also began publishing an annual survey of compensation for priests, listing them not by name but by congregational size and budget and years of experience. Logue then identified priests who were paid much less than their peers and either worked with their vestries to establish a plan for more appropriate pay or helped the priests move to a parish that could pay them appropriately. Within four years, the median pay for male priests increased 8%, while the median pay for female priests increased 20%, adjusted for inflation, according to Logue.

“You just really have to go on and address the outliers, and we found it was helpful to congregations, and we still do it every year,” Logue told ENS. “We were able to, by force of policy, make some changes so that if you’re at the same size church, similar budget, similar Sunday attendance, that you’ll be paid the same.”

Other dioceses, like California, have followed this lead, publishing annual reports of all clergy salaries – including details on the kind of work they do and the kind of churches they serve, but not names or genders. The Diocese of Los Angeles has also been a leader in establishing consistency in clergy salaries, gathering information about compensation packages from its parishes as a result of a 2006 diocesan convention resolution and Suffragan Bishop Diane Jardine Bruce’s push for transparency in church budgeting.

There are cultural factors that can help, too, like having a female bishop or more diverse search committees.

In Virginia, “we’re blessed with a woman [Bishop Suffragan Susan Goff] who is our ecclesiastical authority,” said Thorpe, “and an assistant bishop [the Rt. Rev. Jennifer Brooke-Davidson] who is a woman. That model of leadership, of strong and clear and graceful leadership, it has an effect on folks. And as vestries and search committees have more diverse and, frankly, younger people in leadership, and having more women in those groups, it does make a difference.”

Even so, Thorpe said, seeing the effects of those changes takes time – and a lot of patience.

“It’s improving slightly, but we are a large battleship, so moving the ship takes a little time. We are seeing more willingness and actually enthusiasm about female candidates for positions in larger churches, and that’s a lovely thing,” she told ENS.

“It seems like in 2021, we shouldn’t have to be fighting this battle. But we still have to be fighting this battle.”

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu