Clergy living with mental illness find healing through speaking outPosted Jan 19, 2021 |

|

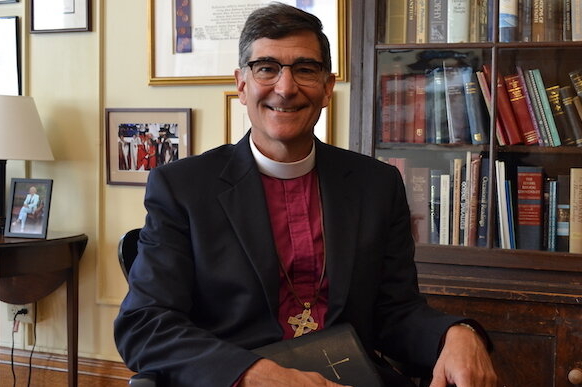

[Episcopal News Service] For decades, New Hampshire Bishop A. Robert Hirschfeld quietly sought treatment for depression, reluctant to admit publicly to the mental health condition underlying his otherwise jovial personality.

Hirschfeld, who was consecrated in 2012, feared that his ministry might be hampered if he “came out” as depressed. Would congregants still trust him? Would it disqualify him from future positions in the church?

So, like many other clergy living with mental health issues, he kept it to himself. In that darkness, shame takes root, he said.

“Shame says, ‘Not only did I make a mistake, but I am a mistake,’” he told Episcopal News Service. “I am somehow morally and psychologically broken.”

Then, a few years ago, Hirschfeld’s perspective began to change as he witnessed the toll that untreated mental illness was taking on the people of New Hampshire, especially in the form of suicide. The state had the third-highest increase in suicides nationwide from 1999 to 2016. He wanted people to know that depression can happen to anyone, and that talking about it can be profoundly healing. He opened up about his experience with depression in his book “With Sighs Too Deep for Words: Grace and Depression,” released last summer.

Although writing the book was “agonizing,” Hirschfeld said it has brought catharsis and healing, both to himself and the people he serves.

“In New Hampshire, the response to this book has just been so humbling and warming and supportive,” he said. “And it may be because people see that it’s not compromising my work. In some ways it fuels it. It gives more empathy, maybe.”

Especially in a time of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, that empathy can help clergy relate on a deeper level to those who are in pain.

“I know something of suffering,” Hirschfeld said. “I know something of those lacks, those great abysses. … And I’ve learned to be kind of at home in it, and I’m not afraid of it.”

Many Episcopal clergy say they have experienced emotional distress as the pandemic has dragged on, partly because of the complex needs it has brought out in their parishioners. People often turn to clergy for support with urgent spiritual and emotional concerns, making them “first responder[s] for the human soul,” as one priest put it.

Hirschfeld says some clergy can become so focused on their roles as leaders and caretakers that they neglect their own needs, sealing off negative emotions behind a mental wall.

“Just as I proclaim the Gospel, the good news, and seek to know and experience and also share the joy of the good news, that doesn’t preclude my being unhappy and having struggles,” he said.

If clergy don’t address personal struggles, they can wreak damage on themselves and those around them, says the Rev. Ed Cardoza, the co-founder of Still Harbor, a spiritual direction center in Arlington, Massachusetts, and the rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Foxborough.

The clergy he counsels have often acted out in some way or are already in the throes of a mental health crisis by the time they are referred to him, he told ENS. In nearly three decades of this work, 2020 stands out.

“I would say that since March, this is the most significant moment in terms of real challenges around mental health,” Cardoza said. He also has begun to see more priests coming to him before reaching the point of crisis, who are “saying, ‘I can hear the shutters on my personal house beginning to bang, and I know that there’s something really, really wrong, and if I don’t take care of it, I’m really afraid of what’s going to happen.’”

Some dioceses have initiated programs to assist clergy. The dioceses of Newark and New Jersey, for example, have established a “warm line” for clergy to call if they are not necessarily in a state of crisis but just want to talk. The Church Pension Group also offers an employee assistance program that provides free counseling sessions – including unlimited, 24-hour phone service – to anyone covered by its medical plans.

Clergy members’ mental health affects not only them and their families but the people in the community who rely on them, Cardoza said.

“It’s not just that they’re worried about themselves,” he said. “They’re one of the lifelines to community.”

The mental health struggles of the clergy can mean the success or failure of congregational life, said the Rev. David Peters, a church planter in Pflugerville, Texas. Like Hirschfeld, he and the Rev. Kathryn Greene-McCreight, priest affiliate at Christ Church in New Haven, Connecticut, have recently written books about their experiences with post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder, respectively. Both say sharing their experience helped them overcome shame and guilt.

Peters developed symptoms of PTSD after returning from his 2005-2006 service as an Army chaplain in the Iraq War. Small, enclosed spaces like racquetball courts sparked panic attacks. His marriage had ended, his faith was damaged and he was experiencing suicidal thoughts, he told ENS. He remembers when he first went to counseling – after returning from Iraq but while still in the Army – looking around the waiting room to make sure nobody he knew was there.

“The stigma was like, ‘You’re weak. You’re not able to handle things,’” he told ENS. Clergy may feel a similar kind of shame, but the narrative is more about moral weakness – a sense that they have failed to appreciate the joy of the resurrection.

Instead, he said, all Christians can take comfort in knowing that they are not alone when they feel pain. The risen Christ is a living symbol of post-traumatic healing, he said.

“Even in his healed state, his resurrected state, he still is the post-traumatic Jesus,” Peters said. “He comes to us that way, with his wounds in front of him, saying, ‘This is me. Look at me. I’m the wounded one.’ … That to me is one of the many messages of the cross. You’re not alone in your suffering.”

Some priests may not want to admit they need help because they view themselves as the ones who tend to others’ needs, not the other way around, Greene-McCreight told ENS.

“I do think that vulnerability is at the heart of why clergy don’t get help, because they don’t want to admit that they are vulnerable like their parishioners are,” she said.

Hirschfeld, Peters and Greene-McCreight agree that fears of parishioners’ losing trust in them because of a mental health diagnosis are mostly unfounded. In fact, they said, parishioners want to know what’s going on with their clergy and help if they can.

The Rev. David Peters blesses a veteran at an Episcopal Veterans Fellowship healing service in 2017. Photo: Brian Diggs/Faith & Leadership

“Hiding or trying to hide how I’m doing from the flock is actually not helpful. In fact, it causes more conflict and more tension [for] them,” Peters said. “I think most people are really happy when clergy are seeking help because those are the ones who are healthy.”

Cardoza said that, in addition to getting the treatment they need and regularly taking time off to rest, “priests need to preach about this. … It begins to normalize what a large portion of our people are going through.”

And despite the toll that mental illness can take, clergy who live with it and manage it can develop resilience and empathy that enhance their ministry, those interviewed for this story said.

“That’s the goal of the healing journey – when you can come out of it and say, ‘I have some knowledge for the community that will help us get through the next thing,’” Peters said.

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu