As COVID-19 upends traditional worship models, Episcopal churches go beyond buildingsPosted Sep 4, 2020 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, it is clear that what many in The Episcopal Church thought at first would be a temporary disruption – a few Sundays away from church and then a joyous return to normalcy – is now the new normal. While some churches have resumed in-person worship, either outdoors or with limited capacity, most are primarily relying on online worship for the foreseeable future.

Despite the horrific toll it has taken, the pandemic has also offered an unprecedented opportunity. As churches reset and adapt, there are hints of what a successful new normal might look like.

“Let’s not just hunker down. Let’s innovate,” Atlanta Bishop Rob Wright told Episcopal News Service. “We see that people are really [focused] on getting Communion back and getting into the buildings again, but we feel like now’s the time to accelerate innovation. We feel like COVID, in all of its loss and grief and hardship, has also created an opportunity for us. And so what we’re worried about is not wasting this moment.”

Wright wants the church to get more comfortable with liturgical experimentation – or “improvisation as fidelity.” He likens it to a jazz standard: a familiar tune with a recognizable melody at its core, performed in a unique way by virtue of inspiration. And he’d like to see more bishops turning away from their sheet music and improvising.

“I feel like it’s incumbent on those of us – bishops, especially – entrusted with status quo. If we can put our imprimatur and fingerprints on innovation and experimentation and run the risk of marvelous failure, then that might send the right signal to people,” he said.

So far, though, the experiments Wright’s diocese has undertaken have seen success. Since the start of the pandemic, the Diocese of Atlanta has been busy rolling out new initiatives like Imagine Church, a monthly online worship experience that premiered Aug. 23. It features high production values, musicians performing contemporary music, personal reflections, a Scripture passage that speaks to the present moment and a sermon from Wright – all in 27 minutes.

Wright says it was born out of an effort to “distill the very best parts of our worship as Anglicans and Episcopalians” and adapt it specifically for online worship, rather than just recording traditional worship services and livestreaming them. Each Imagine Church video premieres on Facebook Live but is prerecorded and available to watch any time.

“People may need a good word and a good song on Thursday, or on Monday morning, or whatever it is. So we want to put what we think is worship with Jesus at the center in people’s hands when they need it in the way that Netflix puts [out] content,” Wright said.

The response has been “overwhelmingly positive”: about 5,000 views in 24 hours for the first video, as well as enthusiastic feedback. Also this year, the diocese has successfully transformed Wright’s weekly devotional into a podcast called “For People” and launched a video series called “Movements of Faith,” geared toward people who are undergoing changes in their spiritual lives.

The proliferation of online worship in all styles and formats should force churches to get creative and think carefully about what they can offer that others can’t, says the Rev. Andrew McGowan, president and dean of Berkeley Divinity School at Yale University. Under the pre-COVID norm, the biggest factor in choosing a church to attend was geographic proximity. That’s no longer the case.

“I certainly hear plenty of people kind of doing the Zoom equivalent of channel surfing as they look at these different possibilities,” McGowan told ENS. “If people have been going to a place because of their sense of the liturgy, and if the liturgy is now an open market online, why would you go to the place online that’s in the reach of your driving capacity when you could go somewhere that does it better – just the style you want?”

McGowan doesn’t see “channel surfing” as a bad thing, though. He looks at it through the lens of Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruption, which “doesn’t invert or erase everything that came before it. Rather, something happens which rearranges all the pieces and adds some new pieces.”

Recording equipment is set up to livestream a worship service at Christ Church in Bronxville, New York. Photo: Christ Church Bronxville

McGowan hopes that Episcopal churches will continue to embrace online worship, not just as a temporary measure during a crisis but as a valuable resource that other churches have been investing in and benefiting from for years. The church as a whole has been too focused on maintaining its traditional structure – the building at the center of town that everyone flocks to on Sunday – to realize that the world in which it was effective has essentially vanished.

“I don’t think The Episcopal Church has distinguished itself by its capacity to foster those [new worship options], I must say, because … The Episcopal Church’s worshipping and ministerial life is so focused on the unit of the congregation that there’s an almost perverse disincentive to foster things that will have new forms whose relationship to our sort of existing business model can’t yet be reimagined,” McGowan said.

That “business model,” which revolved around the weekly in-person celebration of the Eucharist, was not particularly effective even before COVID, at least according to massive declines in attendance statistics in recent years. The Rev. Tom Brackett, manager of church planting and redevelopment for The Episcopal Church, notes that the Eucharist as Episcopalians know it may be mystifying to the rest of the increasingly secular world.

“Church people tend to be hungry for the Eucharist, and the world around the church, the world outside the church is hungry for the shared meal that Jesus offered,” he said.

Altering the Eucharistic liturgy has been something of a third rail in The Episcopal Church for years, but COVID may be changing that. Is Communion celebrated via Zoom – with priests consecrating hosts in parishioners’ homes via video chat – better than having no Communion at all? While the church is not authorizing remote Communion anytime soon, a growing number of Episcopal leaders are willing to entertain the idea, and some say it’s not as revolutionary as it may seem. After all, technological developments have been driving liturgical changes for centuries, McGowan points out.

“The only thing that’s new is the capacity of the internet to emulate community in a slightly more convincing way than, say, television or the telephone could do. The book is a great analogy to this. The rise of books and the rise of printing changed the way in which we relate to worship in a radical way. To then somehow imagine that so-called virtualization of the delivery of the internet has tripped us into some new world relative to what those other things did is, I think, simply a fallacy.”

Brackett expects more and more Episcopalians will celebrate “agape meals,” which are held in memory of Jesus but do not include the consecration prayers contained in the Book of Common Prayer. And there’s a growing sense of understanding across the church of the idea of “universal communion” or “spiritual communion” – the notion that the benefits of the Eucharist are received, if one desires them, whether a person is able to consume the host or not.

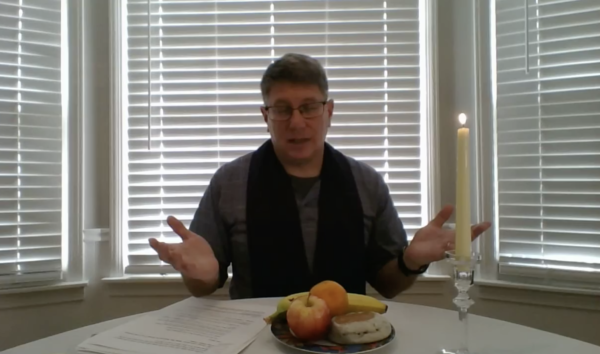

The Rev. Tommy Matthews, associate rector of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Snellville, Georgia, celebrates an agape meal with parishioners via livestream on March 22, 2020. Image: St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church

“Eucharist is something that’s done by a physical community in one place,” McGowan said. “And yet it’s always been possible for people who couldn’t be in community in one place to have a sense of the body of Christ, supported by and informed by whatever forms of technology they had. … The Eucharist doesn’t exhaust the body of Christ.”

The upcoming revision of the Book of Common Prayer may address some of these ideas, but until then, Episcopal churches are continuing to experiment and find new ways to stay engaged in the COVID era. Although the logistics and practical realities have presented enormous challenges, church leaders are finding that their message is even more relevant now, as people struggle to find hope amid suffering and anxiety. This is not the end of the church, they say; it’s exactly what the church was built for.

“COVID is providing an ideal precondition for the preaching of the gospel,” Wright said.

“We have a long Judeo-Christian history of thriving in, not just complicated or difficult situations, but complexity,” Brackett said. “Times like this sharpen our focus on that space from which emergence shows up. And it’s that space between chaos and order.”

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu