Anglican, Episcopal churches continue to serve, advocate for migrants and asylum-seekers in the Americas during COVID-19 pandemicPosted Jun 4, 2020 |

|

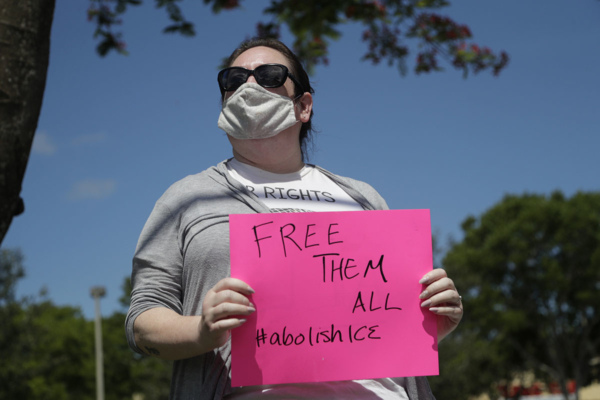

Sarah Bosch-McGuinn wears a protective face mask as she protests outside of a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement field office on May 29, 2020, in Plantation, Florida. Immigrant rights groups are protesting conditions at ICE detention centers due to the potential spread of the COVID-19 virus. Photo: Lynne Sladky/AP

[Episcopal News Service] Over 6.5 million people worldwide have tested positive for the coronavirus, and more than 387,000 have died, the vast majority – 107,728 – in the United States.

Beginning with China in January, government-issued stay-at-home orders aimed at slowing the spread of the virus have shut down all but essential businesses and services in most countries, causing a global recession and leading to more than 40 million unemployment claims in the U.S.

As the virus has circulated around the globe, populist and authoritarian governments have used it as a means to consolidate power, violate citizens’ rights and close borders.

In mid-March, the Trump administration closed the U.S.-Mexico border to nonessential travel, effectively halting immigration and suspending access to the U.S. asylum system.

Around that same time, Mexico restricted all nonessential border crossings, and the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras closed their borders to all traffic. As countries’ health care systems have struggled to treat the volume of COVID-19 patients – in some cases, whole systems have collapsed – the ongoing humanitarian crisis affecting migrants and asylum-seekers at various stages in their journeys continues unabated.

“Governments have had to focus their efforts and attention on the [response to the] pandemic in order to protect their citizens. The migrants are now invisible. It is as if they do not exist anymore. No one takes care of them, even when they are now more vulnerable,” the Rev. Glenda McQueen, The Episcopal Church’s staff officer for Latin America and the Caribbean, told Episcopal News Service. “The church is called to raise its voice and take action in order to help the migrants.”

In recent years, the majority of migrants and asylum-seekers arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border come from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, which form Central America’s Northern Triangle, a region plagued by violence and economic insecurity.

Throughout the pandemic and while responding to the crisis locally, the churches and affiliates of The Episcopal Church’s Province IX dioceses and the Anglican provinces of Central America and Mexico have continued to share information, serve and advocate on behalf of migrants and asylum-seekers.

Throughout the Americas, Anglican and Episcopal churches’ response has become increasingly coordinated over the past several years, especially since 2014 when unprecedented numbers of unaccompanied youth began arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border, and 2018 when the Trump administration began its family separation policy, which detains parents and children in separate facilities.

“The Episcopal Church was no great supporter of the pre-pandemic enforcement regime and has long supported alternatives to immigrant detention. In the face of a virus easily spread by contact in close quarters, our government has an obligation to ensure the health and well-being of all those in its custody, including detained immigrants,” wrote Rushad Thomas, a policy adviser working out of The Episcopal Church’s Washington, D.C.-based Office of Government Relations, in a May 11 blog post on the dangers of detention during COVID-19.

“Even in the absence of a pandemic, there are far better ways to monitor those undergoing immigration removal proceedings than keeping asylum seekers in detention. Detention unnecessarily exposes immigrants to prison-like conditions. The Episcopal Church has long supported alternatives to immigrant detention that maintain family unity and provide immigrants with access to the physical and mental health supports they need,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas’ post came just days after California health officials confirmed that a 57-year-old Salvadoran immigrant detained by ICE since January had died of COVID-19. Since the death, 139 detainees in the same San Diego facility have tested positive for the coronavirus.

In the United States, there are more than 200 immigrant detention centers, many of them private, for-profit institutions under contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, where some 25,000 immigrants are currently held. The 25,000 figure is about half the usual number of immigrants held in U.S. custody, indicating expedited deportations since COVID-19 cases spiked. Sixty detention centers have reported positive cases, according to Freedom for Immigrants, a nonprofit aimed at ending immigrant detention.

During a May webinar on prophetic action and a compassionate response toward immigrant detention during COVID-19 hosted Episcopal Migration Ministries, participants learned that Texas, Louisiana, Arizona, California and Georgia have the highest number of immigrants in detention facilities. Participants also learned about conditions inside those centers.

In a follow-up conversation, the Rev. Leeann Culbreath, a webinar panelist who works with the South Georgia Immigrant Support Network, told ENS one of the most important things Americans need to know is that immigration detainees are not criminals; they may have overstayed a visa, committed a traffic violation or been caught in an ICE raid.

“They are in civil detention, which means they have a civil violation. They have not committed a crime. If they are charged with a crime, they will go through the criminal justice system,” said Culbreath, a deacon at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church in Valdosta, Georgia. “They are waiting for their case to move through immigration court, not the criminal court system. … They are prisoners of policy; if the policy changed tomorrow, they could be monitored in other ways.”

Conditions inside immigrant detention facilities that do not allow for the social distancing protocols recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a lack of soap have put an already at-risk population at greater risk of exposure to the virus. In the South Georgia detention center Culbreath serves, female migrants have voiced their fear and protested dangerous conditions.

By late May, the coronavirus’ epicenter had moved to Latin America. In El Salvador, deportees coming from the U.S. have been quarantined up to 30 days in outdoor tent communities. The U.S. government has been criticized for its role in spreading the virus – a problem the church is addressing.

Today, the Anglican Diocese of Northern Mexico, in partnership with local agencies, operates two migrant shelters in church buildings in Ciudad Juárez across the border from El Paso, Texas, a major port of entry for migrants and asylum-seekers. The shelters have primarily served Central Americans waiting to enter the U.S. and Mexicans who have been deported from the U.S., said the Rev. Héctor Trejo, a vicar serving three Anglican churches in Juárez.

Since April, however, the facilities have served as “filter shelters,” as health officials have enforced protocols to contain the virus by separating new arrivals and quarantining deportees for 14 days before moving them to larger state-run shelters.

The Episcopal Diocese of Rio Grande, which covers New Mexico and far West Texas, including El Paso, is one of Trejo’s partners. Rio Grande also operates a bridge chaplaincy, which began as a way to accompany migrants waiting their turn to make an asylum claim and enter the U.S., but that too has shifted in response to the pandemic.

“The accompaniment part is huge for us, and we are figuring out how that works when we cannot travel,” the Rev. Lee Curtis, Rio Grande’s canon to the ordinary, told ENS. “Our relationships are what we’ve got and carry us through.”

Some six hours’ drive west of El Paso, the Diocese of Arizona, along with the Diocese of Western Mexico, ecumenical partners and the state of Sonora, operates a seven-building shelter in Nogales, Mexico, providing beds, food, medical care, ESL and legal assistance to migrants and asylum-seekers just across the border from Arizona.

The 200-capacity shelter – known as “La Casa” – covers 5 acres, including a garden, two playgrounds, and an isolated infirmary where incoming migrants are quarantined for two weeks, the Rev. David Chavez, the diocese’s missioner for border ministries, told ENS.

“On our end, we’re following CDC protocols. Folks are screened as they come, before they are integrated into the larger La Casa community,” he said, adding that during the pandemic the number of migrants staying in the shelter has been kept to around 130.

Migrants typically stay between six weeks to three months or more, though it is not intended as a long-term shelter. The pandemic has forced services like ESL courses and immigration law clinics online, as U.S. volunteers are cautioned not to travel across the border during the pandemic.

“We are trying to figure out a way to provide that level of educational preparation, legal preparation, medical attention and any other way to serve our residents as a way to prepare them for the next step in their immigration journey,” Chavez said.

Though international borders have closed to all but nonessential traffic, migrant deportations have continued throughout the lockdown, raising fears that the U.S. is deporting migrants infected with the coronavirus. In late March, days after Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador enforced lockdowns, deportation flights arrived as the Department of Homeland Security evacuated U.S. citizens.

“Amid this crisis, migrants are suffering the most and their vulnerability is even higher. … The lack of government measures to support migrant families is outrageous,” El Salvador Bishop David Alvarado told ENS.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the church, government and nongovernment partners provided food, health and social services to returning deportees and refugees in El Salvador’s resettlement program (the Anglican-Episcopal Church of El Salvador, part of the Anglican Province of Central America, has long resettled refugees). For now, however, Alvarado said, the church has turned its focus to assisting migrant families.

(Earlier this year, ICE deported Alvarado’s 34-year-old son following a period of detention in Ohio.)

The Salvadoran church and the Episcopal-affiliated organization Cristosal are working to protect citizens’ constitutional rights. El Salvador’s government moved quickly to contain the virus’ spread by imposing strict quarantine measures and temporarily suspending citizens’ constitutional rights, which international human rights organizations have criticized as an abuse of power.

To the northeast in Honduras, which along with El Salvador shares a western border with Guatemala, migrants continue to cross through porous sections of the land border, and deportees remain in borderlands awaiting another chance to go north, Bishop Lloyd Allen, who leads the Episcopal Diocese of Honduras, told ENS.

“There are spots at the border where the government has no control,” Allen said. “Many deported migrants stay around in order to start their journey one more time.”

In the long term, as the virus’ impact worsens preexisting gross economic inequality and violence, Allen and Alvarado said they expect forced migration from Central America to increase.

In South America, the Episcopal Diocese of Colombia is providing food and other basic necessities to Venezuelans along the countries’ shared border. Venezuela’s ongoing political and economic crises have caused 5 million people to flee, 80% of whom remain in the region.

Migrant traffic along the border has not stopped, and nearby churches are serving lunch every day, Diocese of Colombia Bishop Francisco Duque, told ENS.

“It is a coordinated work. The local police support us when we distribute food, especially amid the pandemic. They make sure people maintain [physical] distance in the lines and wear masks. The last thing we want is to create more chaos than the one we are already experiencing,” Duque said.

At the start of the pandemic, thousands of Venezuelans fled Colombia’s lockdown and began the journey home.

Hampered by a fuel shortage, the Diocese of Venezuela struggles in its response.

“We would like to do so many things, but our reality reminds us that is not an easy task,” Coromoto Salazar, a member of the diocese’s Standing Committee, told ENS. “The other day we wanted to visit some communities, and we could not even move from one place to another given the fuel shortage.”

– Lynette Wilson is managing editor of Episcopal News Service. Clara Villatoro, a journalist based in El Salvador, contributed to this story.

Social Menu