Episcopalians respond to black Americans’ disproportionate number of COVID-19 deaths with lament, community action, advocacy, spiritual carePosted Jun 1, 2020 |

|

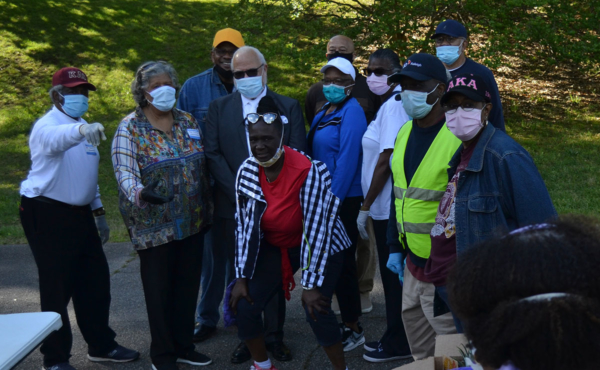

Members of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church in Raleigh, North Carolina, gather May 2 to package and distribute food for the local community. Photo: Carl Harper

[Episcopal News Service] Grappling with the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 virus on black Americans, Episcopalians are responding with formal lament, community engagement, advocacy and spiritual care.

Over 350 people attended the first of three online webinars, “A Cry to God Together: Lament in the Time of COVID-19” hosted by the Diocese of Atlanta’s Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing. It will host its final webinar in the series on June 2, featuring Atlanta Bishop Robert C. Wright.

The webinars were designed “to publicly proclaim a sense of the grief and loss and anger and then be open to some possibility for transformation,” Executive Director Catherine Meeks told Episcopal News Service. “We are more likely to be open to transformation if we’re honest about where we are.”

Meeks called national statistics revealing that African Americans are dying at 2.4 times the rate of whites from the coronavirus “disturbing, but not surprising because of all the factors that have grown out of our history and the lack of concern for black people that makes resources scarce. When you get hit by something like this virus, all the vulnerabilities show up.”

Included among those vulnerabilities are longstanding stressors, such as systemic racism, poverty and lack of access to adequate education and health care. The COVID-19 virus has added another layer of stress, she said.

The need to lament “grew out of hearing people saying, ‘Well, we just have to do this until we get back to normal.’ There’s no normal to get back to,” Meeks said. “We’ve got to move forward. We have lost some ways of being and there’s a lot to grieve, but if we don’t pay attention and do that work, we will flounder a long time.”

Similarly, the Rev. Ron Byrd, The Episcopal Church’s missioner for Black Ministries, said he has begun online monthly check-ins with clergy of African descent to offer “an opportunity to share their grief, share their challenges, share their opportunities, share what they’re doing to share with others in this age of COVID-19.”

Emerging on the pandemic’s other side will be a hybrid of traditional church and new technologies, along with fresh expressions of stewardship, advocacy and missional opportunities, he said.

“We are not entering a new normal, but a new reality,” Byrd told ENS. “For African Americans in general, and clergy of color in particular, we don’t want to go back to normal. Normal was not serving us.”

In Philadelphia: Historic strength, community engagement

In Philadelphia, where black patients are dying at a 30% higher rate than white patients, the Very Rev. Canon Martini Shaw, in mid-May, averaged three COVID-19-related funerals a week for three weeks.

Administering spiritual care to the bereaved while wearing a mask and social distancing with only a handful of family members present “creates a terrible barrier,” he said. He recalled one such service at a local funeral home with “a widow sitting in front of her husband’s casket, bereaved and sobbing. Neither I nor family members could really go to her to offer her any type of physical support.”

Additional stressors include “providing care for those who are suffering, dying, those who have died, and just tending to those who are sick, or staying in touch with those who might have lost their jobs and be suffering hardships financially and providing food for them,” he said.

For spiritual sustenance Shaw, rector of the historic African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, harks back to the church’s roots. The congregation was founded in 1792 by Absalom Jones, The Episcopal Church’s first black priest. Jones, a former slave, worked tirelessly among victims of a yellow fever outbreak in 1793.

“We are continually inspired by the ministry of Blessed Absalom, especially during this time of COVID-19,” Shaw told ENS during a recent telephone interview. “Blessed Absalom’s commitment to the community during the yellow fever epidemic fuels our passion, dedication and witness to serving God’s people today.”

Shaw has shifted Bible study and worship online, on Sundays, as well as daily morning meditations and evening compline. Church partnerships with the Overbrook West Neighbors Community Development Corporation and Project Isaiah have meant that “we help provide food to seniors and those people in the community who are suffering financially. A truck delivers weekly meals — at least 1,000 boxes of food were distributed just last week.”

Additionally, the church will serve as a testing site for the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, a group offering free testing to the community, Shaw said. “Every week seems to be different; I don’t always know in advance what the needs might be, but we are standing ready and willing to assist.”

In Raleigh: A vision of ‘worship, wisdom, work’

In Raleigh, North Carolina, the COVID-19 virus may have temporarily emptied the parking lot and shuttered doors at St. Ambrose Episcopal Church, but the 500-member congregation’s focus has remained steady: “We give worship to God, we receive wisdom from God and we work alongside God.”

St. Ambrose’s rector, the Rev. Jemonde Taylor, said volunteers recently experienced a sense of communion when assembling and distributing 11,500 boxes of food in the community.

After a brief morning prayer service, volunteers made “the connection between the worship we did in the past when we gathered and that this is the worship we do now, keeping us connected now that the church is scattered.”

In a state where twice as many African Americans as whites are living in poverty, are unemployed and are food insecure, the church’s outreach has focused on alleviating hunger and advocating for housing relief, primarily through community partnerships.

In North Carolina, African Americans represent 22% of the state’s population but account for 39% of COVID-19 deaths.

Concerns about social isolation as well as the concrete needs of the most vulnerable have translated into door-to-door food distribution, Forward Day by Day drop-offs and friendly greetings through windows — not just for parishioners but the community in general, he said. Forward Day by Day is a lectionary-based collection of daily Christian meditations, published quarterly by Forward Movement, a ministry of The Episcopal Church.

“We have the same concerns as everyone — isolation, being lonely,” Taylor said. “I talked with one parishioner in her 90s who wonders if she will ever worship in St. Ambrose again. At her age, she is wondering if her last Sunday in our worship space was March 8th,” after which in-person worship was temporarily suspended.

Prayer meetings and other spiritual resources, including a coronavirus-inspired sheltering-in-place Bible study, have been offered online and via telephone, he said. “We began with Noah’s Ark, the great story of quarantine and sheltering in place — eight people in a big boat with all of the animals for a long time,” he said.

Advocacy: The church’s responsibility

The Rev. Kim Jackson, interim vicar of Church of the Common Ground, which meets in a downtown Atlanta park, said at least nine COVID-19 cases and one death had been reported among her chronically homeless congregation.

The church has a responsibility to lament on their behalf, she told viewers of the Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing’s May 19 webinar. “Their energy is focused on surviving,” she said. “What does it mean to be in a space where survival is your fundamental purpose and goal, so you can’t pause and cry out in the ways you might want to?”

She questioned why such COVID-19-inspired changes as housing the homeless in empty motels and early prisoner release hadn’t happened before the virus. “If we could do that today, we could have been doing it all along,” she said.

The Rev. Charles Wynder Jr., The Episcopal Church’s staff officer for social justice and advocacy engagement on reconciliation, justice and creation care, agreed.

“Lamentation is an important part of our ability to grieve,” and so is advocacy against such long-standing systemic inequities as racism, poverty, lack of access to education and healthcare,” Wynder said. “Advocacy is critical to our ability to come through this and come out on the other side equipped to be able to live and to be positioned for human flourishing. The question is, What is the church willing to do?”

– The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a correspondent for the Episcopal News Service. She is based in Los Angeles.

Social Menu