Church’s grassroots efforts help Navajoland feed families impacted by COVID-19 outbreakPosted May 14, 2020 |

|

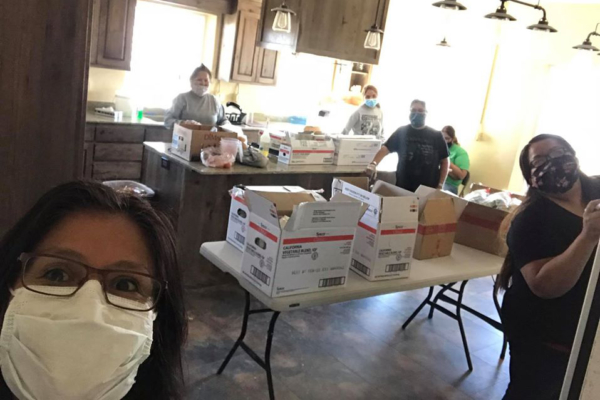

The Rev. Cornelia Eaton poses for a photo May 5 with volunteers as they sort food for distribution to communities near Navajoland churches. Photo: Cornelia Eaton, via Facebook

[Episcopal News Service] An outpouring of support from around the country has enabled the Episcopal Church in Navajoland to deliver emergency food and supplies to more than 100 families on the Navajo Nation reservation, which has one of the highest concentrations of COVID-19 cases in the United States.

The Navajo Nation tribal government reported this week that 119 people have died after contracting the coronavirus, and the Navajo Nation’s number of confirmed cases has grown to about 3,400. That reportedly places the reservation’s per capita rate of infection higher than that of any state, though worse outbreaks have been identified in some U.S. cities and counties.

About 175,000 people live on the reservation, which covers more than 27,000 square miles in the Four Corners region of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. More than 30% of households lack running water, and many residents live below the poverty line in isolated villages far from the nearest grocery store. Tribal curfews intended to slow the coronavirus’ spread have made it even more difficult for families to access food and clean water.

“The need has always been there. … The pandemic has just exacerbated the problem,” Navajoland Bishop David Bailey said in a phone interview with Episcopal News Service.

Navajoland’s clergy and lay leaders got a big boost to their feeding ministries from a national fundraising effort launched by the Diocese of Northern Michigan, which raised $40,000. A diverse group of church leaders and businesses nationwide offered logistical and delivery assistance, and volunteers in recent days have traveled village to village to distribute the food.

Northern Michigan also is organizing an online benefit concert June 11, called Indigi-Aid, to raise money to support indigenous ministries across The Episcopal Church during the pandemic. The diocese is lining up musicians, dancers, storytellers and other artists and performers for the four-hour event, to be structured like an old-fashioned telethon.

“It kind of was just this grassroots, scrappy idea that has grown into to something that people feel excited about,” the Rev. Lydia Kelsey Bucklin, Northern Michigan’s canon to the ordinary for discipleship and vitality, told ENS.

Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to coronavirus outbreaks due to a range of factors, including high poverty rates, frequent underlying health conditions and limited access to clean water for handwashing. And although population density is low across the Navajo reservation, extended families typical live close together in villages, sometimes with several people in one house, making it difficult to practice the physical distancing that is one of the most effective ways of slowing transmission of the virus.

Tribal governments and councils have issued lockdown orders on reservations in the U.S. mainland and in isolated villages home to Alaska Natives to try to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Those measures sometimes have run counter to state policies, notably in South Dakota, where Gov. Kristi Noem has objected to two tribes’ precautionary checkpoints on state and U.S. highways. So far, no coronavirus outbreaks have been reported on those two reservations, Pine Ridge and Cheyenne River – a marked contrast to the ongoing crisis on the Navajo reservation.

A large church gathering on March 7 in Chilchinbeto, Arizona, is suspected of partly fueling the Navajo Nation outbreak. In their attempt to slow the spread of the virus, tribal leaders declared a state of emergency on March 13 and have implemented overnight and weekend curfews restricting travel.

“With some states starting to reopen, it’s giving people the impression that it’s okay to go out into public, but it’s not safe yet,” Navajo President Jonathan Nez said in a May 13 news release. “With today’s numbers, it’s clear that everyone needs to step up and hold each other accountable to stay home.”

In 1978, The Episcopal Church carved out sections of the dioceses of Rio Grande, Arizona and Utah to create the Navajoland Area Mission, an effort toward unification of language, culture and families. The churchwide triennial budget now includes a $1 million block grant to support Navajoland. In recent years, the church’s Development Office also has worked with Navajoland leaders to strengthen their local fundraising efforts.

The Diocese of Northern Michigan is active in indigenous ministries as well. Of the 12 federally recognized Native American tribes based in Michigan, five are in the state’s sparsely populated Upper Peninsula. Bishop Rayford Ray, Bucklin and other diocesan officials keep in contact with their counterparts in other dioceses through a loose network of indigenous clergy and other ministry leaders serving American Indian communities.

In late March, they started sharing their experiences weekly via video conference calls organized by the Rev. Bradley Hauff, The Episcopal Church’s missioner for indigenous ministries. Much of the ensuing conversations focused on the worsening COVID-19 crisis on the Navajo reservation.

By mid-April, those conversations grew into a fundraising campaign based in Northern Michigan but extending across the country, with the initial goal of $40,000. The diocese began promoting the campaign on Facebook on April 16, and the homepage of the diocesan website displayed a call for donations.

The campaign received key support from several bishops who were consecrated within a year of Bailey and Ray in 2010 and 2011, including Wyoming Bishop John Smylie, Alaska Bishop Mark Lattime and Utah Bishop Scott Hayashi. Through calls for matching donations from Episcopalians across the church and through direct online donations to Navajoland, the campaign quickly met its goal.

“That’s just one tiny diocese helping another tiny diocese,” Bucklin said. “We felt it’s something we can do, some small thing we can do.”

That small campaign paid off in a big way this month, as efforts to support Navajoland continue to gain momentum in unexpected ways. An individual in Austin, Texas, donated a freezer to store food until it could be distributed. And in the Diocese of the Rio Grande, which includes New Mexico, Bishop Michael Hunn told ENS he was all set to buy food, load it into his pickup truck and drive it from Albuquerque to Navajoland headquarters in Farmington, but a better option materialized.

Rio Grande’s Bosque Conference and Retreat Center was closed because of the pandemic, but its head chef, Jerry Gallegos, told Hunn the center still had an open account with food wholesaler Sysco. Instead of deploying his pickup, Hunn suggested that Bailey work with Gallegos to put in an order for food from Sysco, which made its first delivery – in its own truck – on May 5.

Spirits were high as Facebook posts from Navajoland leaders showed the food being unloaded at All Saints Episcopal Church in Farmington, New Mexico.

“Thank you all for your support and prayers for helping us to serve the Diné as ‘beloved community,’” the Rev. Cornelia Eaton, Navajoland canon to the ordinary for ministry, said on Facebook.

Then on May 6, another truck arrived, this time with food and supplies donated by Giving Children Hope, a nonprofit based in Buena Park, California, a Los Angeles suburb.

The key connection behind that donation was the Rev. Mary Crist, The Episcopal Church’s coordinator for indigenous theological education, who is based in Southern California. Crist knew the nonprofit’s director, and when she explained Navajoland’s efforts, Giving Children Hope was happy to help. Its website also prominently features a call for additional money for Navajoland.

Since last week’s food deliveries, volunteers have ventured through the region to distribute the food to families living in the communities around Navajoland’s 11 congregations.

“This week was a busy week,” GJ Gordy, who serves Navajoland as a communications specialist, said May 8 in a Facebook post about the food distribution. “We got back to Farmington with 5 minutes to spare before the Navajo Nation curfew started at 8 p.m.”

Bailey said Navajoland has received enough money to make additional food purchases, and it is working with tribal authorities to ensure they aren’t duplicating efforts. Navajoland also is thinking ahead to the fall and winter and may use some of the money to purchase in advance some of the coal and wood that residents will need to heat their homes.

The June 11 fundraising concert will allow the Diocese of Northern Michigan to continue to support those efforts, though it will broaden the scope. The Episcopal Church’s Indigenous Ministries Advisory Council will help Northern Michigan identify recipients among all indigenous communities served by The Episcopal Church based on their needs.

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu