‘Miracle moments’ in the season of EastertideCOVID-19 cancels annual pilgrimage to El Santuario de ChimayóPosted Apr 28, 2020 |

|

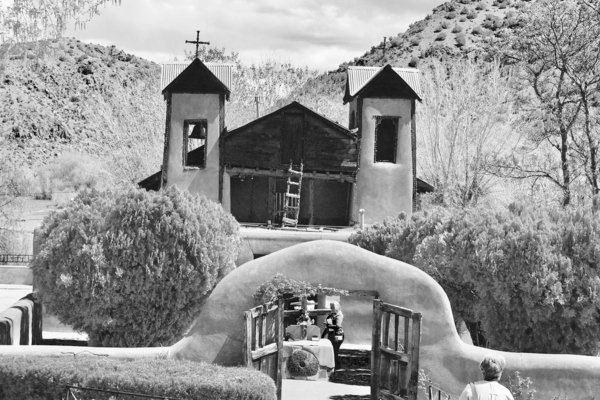

Founded in 1816, El Santuario de Chimayó, in Chimayó, New Mexico, has thick adobe walls, two bell towers and six-foot crucifix, making it a prime example of Spanish colonial architecture. It is best known for the curative powers of the “holy dirt” found in its sacristy. Photo: James L. Overton

[Episcopal News Service] During the penitential season of Lent, on Easter Sunday and during the 50 days of Eastertide, Episcopalians exclaim “Alleluia” and reflect on the mystery of faith.

That many Christians believe the seven miracles of Jesus were historical events and affirmed his divinity is also a thread common to the tri-ethnic religious and cultural history of northern New Mexico.

This is especially true in Santa Fe, New Mexico – the city of the Holy Faith of St. Francis of Assisi – where for decades a growing number of Episcopalians have joined their Roman Catholic brethren for the annual pilgrimage to El Santuario de Chimayó, located in Chimayó, New Mexico.

It is a key spiritual element of Holy Week for The Church of the Holy Faith, an Episcopal church in Santa Fe.

But this year, COVID-19 turned lives upside down, shuttered businesses and schools, and temporarily ended in-person worship and the communion of fellowship.

“I think some within the congregation have been making the pilgrimage for about as long as I can remember,” said Marty Buchsbaum, a cradle parishioner at Holy Faith.

Buchsbaum also spent years with the volunteer fire department in the Village of Tesuque, assisting the estimated 30,000 Good Friday pilgrims making their way along State Road 503 to the ancient village of Chimayó in Northern New Mexico. He remembers seeing Holy Faithers along the way.

“It may have been only a handful, and they almost always joined the Maundy Thursday evening pilgrims. I clearly remember seeing and greeting members of the congregation as we [Tesuque Volunteer Fire District] were out helping to protect them,” he said.

Pilgrims from Holy Faith on the winding road from the pueblo to El Santuario de Chimayó in 2018. Near the center of the picture, one parishioner carries a plain wooden cross. Photo: James L. Overton

The Santuario is considered to be one of the most important pilgrimage sites in the United States, drawing some 300,000 Hispanics, Native Americans and people of other faiths and cultures every year. During Holy Week, it draws pilgrims from all over New Mexico. Some walk more than 100 miles carrying wooden crosses – often left in spontaneous shrines along a chain-link fence – or treading on cactus needles in their shoes to demonstrate penitence or devotion.

Located between Santa Fe and Taos, the Santuario was founded in 1816. It was purchased by the Spanish Colonial Arts Society in 1929 and donated to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe. Today, it is considered a prime example of Spanish colonial architecture with its thick adobe walls, two bell towers and six-foot crucifix.

The mission church has been compared to Lourdes, a major pilgrimage site in France where people come to heal and experience miracles. El Santuario de Chimayó became a National Historic Landmark in 1970.

The Rev. Robin Dodge (left in black cassock) leads pilgrims from Santa Fe’s Church of the Holy Faith in one of the Stations of the Cross during the 2018 pilgrimage to Chimayó.

Its provenance is a legend unto itself. In 1810, a local Penitente was performing his rites when he saw a light coming from a hillside near the Santa Cruz River. Following the light, he discovered it came out of the ground. Further investigation revealed a large crucifix bearing a black Christ. The crucifix was taken to the church in nearby Santa Cruz and hung high above the altar. Three times the giant crucifix disappeared. It was then decided that a chapel would be built over the hole where it was originally discovered. The chapel was later razed to make way for what is now the Santuario.

Not unlike the pilgrims who travel to Lourdes for healing and spiritual enrichment, pilgrims and visitors who come to the Santuario are drawn by the powers of the “tierra bendita” or “holy dirt,” believed by many to have miraculous healing powers. The dirt is found in a small hole in a precept off the main altar. Pilgrims are warned not to eat or drink the dirt but are advised to say silent prayers when rubbing the dirt over body parts that need a healing intervention.

While myth is that the dirt is from a never-ending supply, Chimayó priests have clean fill dirt trucked in from the surrounding hills to routinely replenish the supply in the hole, where it is consecrated. Chimayó is the name of a nearby hill where the soil was believed by Native Americans to have sacred healing powers, long before los conquistadores arrived in the mid 16th century. Soil analysis has shown the dirt to have elevated levels of calcium carbonate.

Belief in the curative powers of the dirt is purely faith based. But pilgrims and the infirm routinely leave behind canes, crutches, rosaries, wooden crosses of all sizes and other iconic religious articles, talismans and amulets in affirmation of their healing and spiritual experience.

Eleanor Ortiz, a retired teacher from Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the wheel of her car. In 2018, Ortiz led the pilgrims by driving ahead to secure locations where Holy Faith parishioners could stop for water and snacks and observe the Stations of the Cross. Photo: James L. Overton

“For years, [Holy Faith] pilgrims making the 11-mile walk to Chimayó would start from the nearby pueblo of Pojoaque. It was later a few miles closer to the church in Nambe Pueblo – only eight miles away. Back then, pilgrims from Holy Faith were fewer than half a dozen. By 2019, the number swelled to some 40 people of all ages,” said Eleanor Ortiz, a member of Holy Faith’s Altar Guild who came to Santa Fe as a newly minted schoolteacher in 1966.

“In those days, the handful of faithful would sit off to the side of the Santuario and do communion,” she said. “Then we would drive back to Santa Fe for a large Lenten New Mexican family-sized meal of salmon croquettes, macaroni with tomatoes and cheese, and calites (spinach, beans and crushed red chile).” Dessert would be torrejas (a sweet bread pudding) and natillas (a creamy Spanish custard).

Upon joining Holy Faith in 2008, Ortiz made her first walk with the late parishioner Janet Kaye, who had done the walk for years. “The funny thing is that Janet would take a bottle of whiskey – for emergencies,” she said.

Many Holy Faith parishioners credit the late rector, the Rev. Kenneth J. Semon, with making the walk an organized observance for the parish with enthusiastic support from the Rev. James Brzezinski, an associate rector. Semon added the 14 Stations of the Cross as part of the pilgrimage.

Parishioner and former Senior Warden Ray Wallace started doing the walkabout a dozen years ago from Pojoaque on Good Friday. In a recent conversation, he lamented this year’s cancellation of the pilgrimage to Chimayó.

“I’ve done it a goodly number of times,” Wallace said. “It’s been a part of my Easter observance for a lot of years, and I did not feel as spiritually engaged this Holy Week because I couldn’t do it.”

Many Holy Faith parishioners share Wallace’s hope that they will once again be able to walk together in faith along the road to Chimayó.

– James Overton, a retired career journalist and network television writer and producer, is a member of Santa Fe’s Church of the Holy Faith.

Social Menu