Michigan’s neighbors, partnerships are key to COVID-19 reliefPosted Apr 22, 2020 |

|

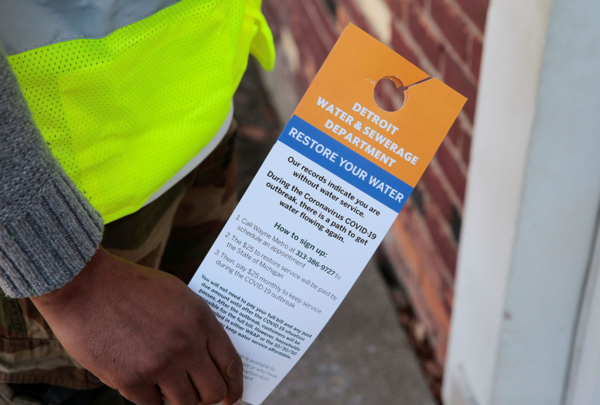

Contract worker Vaughn Harrington distributes notices from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to inform residents how to restore water service in response to the coronavirus outbreak in Detroit, Michigan. Photo: Rebecca Cook/REUTERS

[Episcopal News Service] In the age of COVID-19, Detroit resident Eddie Dukes relies on the kindness of neighbors and St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Corktown, just west of the city’s downtown.

Although disabled and unemployed, the 62-year-old had managed to get by, mowing lawns, shoveling snow, sweeping restaurant parking lots in exchange for meals. But now many restaurants are closed, and he receives food from Manna Community Meals, delivered by neighbor Jeff Debruyn.

“I met Jeff at Manna Meals,” Dukes told Episcopal News Service. “I was homeless. In a way I still am, and I don’t like it, but I am blessed by the grace of God.”

Debruyn, a 15-year employee of Manna Community Meals, said the virus has meant sweeping operational changes for the soup kitchen, which had been based in St. Peter’s basement. Everyone must practice safe distancing, and guests now eat outside rather than indoors. “It has created profound, palpable desperation that I’ve not seen before, yet also an equally profound sense of gratitude. I’ve had a couple of guys cry because we are still open.”

In Michigan, as elsewhere, coronavirus has exposed stark racial and economic disparities. African Americans, like Dukes, represent 14% of the state’s population but 40% of its deaths from COVID-19.

That grim reality moved Michigan Bishop Bonnie Perry to announce a $100,000 matching fund to alleviate food insecurity, in partnership with All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Pontiac and Christ Church Cranbrook in Bloomfield Hills.

St. Peter’s Church in Detroit — in partnership with local water justice ministries — stores cases of bottled water for delivery to area residents whose households are without running water. Photo: Denise Griebler

“There are massive needs,” Perry told ENS recently. “There are more than 1 million people in Michigan who have gone on unemployment in the last few weeks.” The grants will be made throughout the community, not exclusively to Episcopal church ministries, she said. By April 20, the fund had reached nearly half the $100,000 dollar-for-dollar matched goal.

“We’re really clear that we’re in this together,” Perry said. The diocese represents 76 worshipping communities and 16,000 Episcopalians in Southeast Michigan. “The reality is, we exist for people who haven’t yet walked through our doors. In the Diocese of Michigan, I want us to be people who care and who show our care by acting.”

Church’s obligation: ‘a more just future’

Perry hosted an April 14 webinar during which the Very Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary in New York, said the church has an obligation to reach out to those most impacted by the pandemic, “the crucified classes of people.”

“We can begin to close the gap between where we are and a more just future,” she said. “That is the responsibility of those of us who are faith leaders — to boldly fill that breach and lift our voices and make sure those considered expendable in this country don’t now become, with this virus, disposable.”

The webinar, “The Pandemic and Poverty: A Theological and Public Policy Discussion of COVID-19,” also featured as guests University of Michigan Professor Luke Shaefer and Dr. Carla Bezold, chief epidemiologist for the City of Detroit Health Department. It received more than 235 views.

In addition to exposing inequities, the pandemic has placed even greater strain on existing systems designed to aid the vulnerable, according to Shaefer, faculty director of Poverty Solutions. The agency is a University of Michigan research initiative that partners with policymakers, community organizations, governments and others to help confront poverty.

“In other times, you might see your job disappear, but your child is still going to school. But now, jobs have disappeared, schools have disappeared, children lose access to incredibly important services at school,” said Shaefer, a member of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Clinton, a small city 60 miles west of Detroit.

The disparities are multilayered, he added. For example, a lack of technology in the home impacts opportunities for distance learning. Reliance on school nutrition programs and the rise in coronavirus cases and unemployment place a further strain on grocery supplies and distribution sites like food pantries. Volunteers for feeding ministries often are senior citizens and, therefore, at risk of contracting the virus and asked to stay home.

Volunteers load cases of water to deliver to Detroit homes that have no running water. Photo: Courtesy of We the People of Detroit

The lack of running water in thousands of Detroit homes is also a huge challenge, according to the Rev. Denise Griebler, St. Peter’s director of ministry and community engagement. The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department shut off water in an estimated 11,000 city households in 2019.

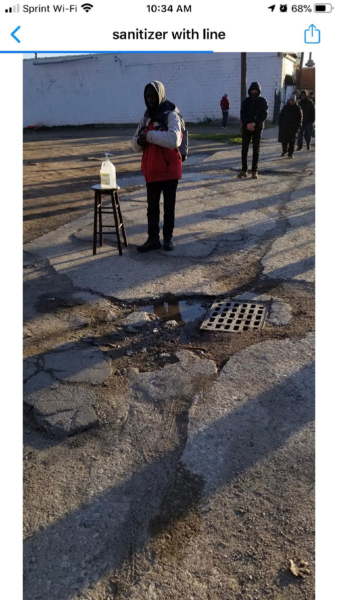

Guests waiting to be served at Manna Community Meals in Detroit – operated by St. Peter’s Episcopal Church and Holy Trinity Catholic Church – practice safe distancing and can access a hand sanitizer station outside the church. Photo: Bob Chapman

A hand sanitizer station has been placed outside the church and — now that worship has been suspended indefinitely as a safety measure — the sanctuary has become holy storage space, stacked with cases of bottled water, she said. Volunteers from We the People of Detroit, a water justice ministry and a St. Peter’s partner, deliver the cases to households that don’t have access to transportation.

“When the first line of defense is to wash your hands right now, as a way to keep from getting sick or spreading it to others — it is horrendous” that water has only been restored to about 1,000 Detroit households, Griebler said.

Even restoring the water is complicated. “When you turn somebody’s water off and leave it off, there’s all kinds of plumbing problems that happen … because of the way metal from the pipes can leach into the water that hasn’t been running at the proper pressure. It’s not like there’s just a switch that can be flipped on,” she said.

Detroit has about 7,736 confirmed cases of the coronavirus. Shaefer said that the city’s “phenomenal job of testing” may skew statistics, as compared to other areas where testing is not as readily available or performed as efficiently. “The city’s response had been extraordinary. Any resident who wants to get tested can go to a drive-through testing place or call and get a ride,” he said.

Nancy Blount is among those residents. She was tested with a cotton swab up the nose after experiencing a fever and severe headache for about three weeks. “You get in lines but have to stay in your car,” she said.

“There are signs saying to keep your windows up. Eventually, you reach tents with tables and medical personnel in protective gear. They test you, then give you a sheet with the next steps on it,” Blount said.

Still awaiting results, she added, “If I test positive, I am going to participate in the Red Cross Plasma Study to help others.”

Feeding the hungry in Pontiac

When concerns about coronavirus halted its after-school youth mentoring program housed at All Saints’ Church in Pontiac, the agency, Bound Together, seamlessly became an emergency food distribution site.

“What we’re doing right now is a no-questions-asked program,” according to Michele Wogaman, Bound Together’s executive director. “The cars pull up. They roll down their windows. We ask how many children they have. They tell us, and we put food into their trunks because the goal at this point — everyone’s goal at this point — is simply to meet the needs.”

Food insecurity is a tremendous issue in Pontiac, a city of 60,000 located about 30 miles north of Detroit. About 80% of the population lives below the poverty line, she said.

Bound Together began 25 years ago as a tutoring ministry of All Saints’ and quickly recognized the need to address food insecurity. Snacks and meals were added, and eventually, it became a separate nonprofit organization but still maintains sessions at the church, she said.

Wogaman said partnerships with local businesses, government and churches are crucial. “When the Oakland-Livingston Human Services Agency asked if we would be willing to serve as an emergency food site, the answer was ‘Yes, please,’” she explained. Additionally, a sewing group at St. James Episcopal Church in Birmingham is making and donating masks, and Wogaman recently received gift cards from a local grocery store for distribution.

“This is a deeply challenging time, but good things are happening,” she said.

Similarly, partnerships with local markets, bakeries and restaurants have sustained a weekend community breakfast ministry at All Saints’. A local prison donates knitted hats and gloves for distribution. The Saturday breakfasts began about six years ago and had grown from about 20 guests initially to an average 170 per weekend, according to facilitator Michael Kobylik.

But coronavirus safety precautions have changed it “from offering hot meals to a walk-up, takeout service,” he said.

Personal care items are in huge demand. “In normal times, we had a giveaway table that included toiletry articles,” Kobylik said. “Toilet paper was always a huge issue for this demographic; now it is a huge issue for everybody. We are working on how we can put together takeaway bags that have all those things — a roll of toilet paper, toothpaste, hand sanitizer.”

Many guests are “under-homed,” according to Kobylik. “It’s not that they’re homeless, but they’re not exactly living in an ideal situation. We gave one gentleman a rug that came to us through a resale shop. He said, ‘This is perfect. This will go right on the floor I sleep on and stop the cold air from coming up.’”

More than anything, the virus has stripped the community of its joy, Kobylik said.

“The first minute I experienced the community breakfast, I said, ‘This is a church service,’” he recalled. “This is a community of people who don’t see each other during the week but come together to share their victories, to comfort each other in their tragedies, to be a community. It’s really pretty cool.”

Debruyn, of Manna Community Meals in Detroit, agreed. “The virus has turned everything upside down” for guests, whose routines have been disrupted, he said. “They can’t find places to go to the bathroom. If they’re thirsty, there’s no place to get water. They can’t get on the Internet. Everything is shut down. There is no place for them to go during the day for any sense of peace.”

Before the virus, William Esters, 50 and homeless, had served as a volunteer at St. Peter’s in Detroit. “Today, I need a shower,” he told ENS on April 20. St. Peter’s also offers showers and laundry services to area homeless. After each use, the room is sanitized and readied for the next guest. “You need to be clean, no matter what situation you’re in,” Esters said.

A former prison inmate who has faced a system stacked against him and barriers to aid, Esters is grateful for the church’s ministries, he explained. “Here, you are able to participate and that makes us feel part of a church, part of a community.”

Esters said, “They don’t judge me. They don’t give me hard criticism or predict how I should live. Or ask me questions about why I’m homeless. I need their encouragement to know that there is going to be a better day.”

– The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a correspondent for ENS. She is based in Los Angeles.

Social Menu