Drive-thru Communion? Remote consecration? COVID-19 sparks Eucharistic experimentation – and theological debatePosted Apr 8, 2020 |

|

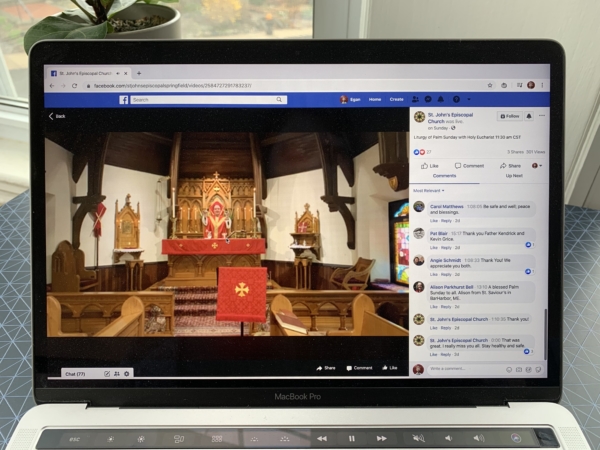

The Rev. David Kendrick, rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Springfield, Missouri, celebrates the Eucharist on Facebook Live on April 5, 2020. Photo: Egan Millard/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] As the COVID-19 lockdown drags on, many Episcopalians are experiencing the longest absence of the Eucharist they’ve had in years – perhaps even in their entire adult lives. While this has been viewed by some as an opportunity for an unintentional Lenten devotion – “Eucharistic fasting” – others have proposed new ways of celebrating the sacrament to provide spiritual comfort at a time when it has never seemed more necessary.

Some of these alternative practices – like “drive-thru Holy Communion,” delivery of consecrated hosts to parishioners’ doorsteps and even “virtual consecration” – have ignited debate within The Episcopal Church about health risks, the appropriate amount of adaptation of sacramental practices to the current crisis and the nature of the Eucharist itself. Is it still the Eucharist if it is celebrated by one priest alone in a church while the congregation watches on Facebook Live? If the priest never touches the bread and wine? If it is consecrated and sent through the mail?

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry recently offered guidance on these and other sacramental questions, but diocesan bishops started encountering these dilemmas several weeks ago as the COVID-19 crisis escalated and churches were forced to suspend in-person worship. Bishop Susan Haynes of Southern Virginia started getting creative suggestions very early on, she told Episcopal News Service.

“When the stay-at-home orders were pronounced, people immediately began to think of ways that they could continue to be a connected worshipping community,” she said. “They looked for ways around the ban on social gatherings and they came up with lots of creative ideas.”

The first suggestion she received was one of the most common alternative Eucharist practices that emerged in the COVID-19 era: a drive-in Eucharist, in which a priest consecrates the host and administers it to parishioners through car windows. Some Episcopal churches briefly held services like these in March, but Curry discouraged them for theological and health reasons in his March 31 letter to the church. Haynes, too, was immediately wary of putting parishioners at risk.

“I was concerned about that because, at the time, we were hearing that the virus was capable of aerosolizing – in other words, it was capable of being in the air,” Haynes said. Some studies have indicated that the virus can spread this way.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Some practices remove an element that has defined the Eucharist since the Last Supper (commemorated on Maundy Thursday): the physical presence of a community celebrating the sacrament together.[/perfectpullquote]

“And if you roll down your car windows to receive the Eucharist, you could be transmitting germs unwittingly to the people who are trying to serve you,” Haynes said. “My primary motivation from the beginning has been the safety of the people, and I’ve been listening to the health professionals and taking my cues from them, and they all say, ‘Stay home.’”

Other ideas raised practical and theological concerns in addition to the risk of transmission. One suggestion, which Haynes quickly turned down, was to send consecrated hosts through the mail.

“While the mail is often very reliable, sometimes it isn’t, and I didn’t want to be reckless with Jesus and have him lost on some postal carrier’s truck, never to be found again,” Haynes said.

A variation that has shown up in other dioceses was to deliver consecrated hosts to parishioners’ homes and leave them at the door. While Haynes “really liked the ingenuity of that idea,” it removed an element that has defined the Eucharist since the Last Supper (commemorated on Maundy Thursday): the physical presence of a community celebrating the sacrament together. Despite the extraordinary circumstances, Haynes was reluctant to break with 2,000 years of tradition.

“The Eucharist is something that we celebrate in community, and the prayers are the work of the community that has gathered,” she told ENS, a view endorsed by Curry in his letter. Though he avoided making judgments of “permissible/not permissible,” Curry wrote that practices like these “present public health concerns and further distort the essential link between a communal celebration and the culmination of that celebration in the reception of the Eucharistic bread and wine.”

Though the rubrics in the Book of Common Prayer do not stipulate that the Eucharist is only valid when celebrated as an in-person gathering, many Episcopalians believe it is understood and implicit in the way the rite is written. Some, however, interpret it differently.

The Rev. David Kendrick, rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Springfield, Missouri, describes his congregation as Anglo-Catholic, and the inability to receive Communion has been particularly difficult for his parishioners.

He asked himself: “Was there a way I could make Communion available in a way that I felt was consistent with the rubrics of the prayer book?”

The last in-person worship was March 15. The next day, Bishop Martin Field ordered a suspension of in-person worship across the Diocese of West Missouri.

On March 22, Kendrick set up a livestream in his office, celebrating Holy Eucharist just through the Liturgy of the Word. He followed up on March 29 with a service broadcast from St. John’s chapel with the church organist as the only other participant, and this time he celebrated a full Eucharist, reserving some of the consecrated wafers.

“I knew I just needed to do something to make Holy Week a little more special for people,” Kendrick told ENS.

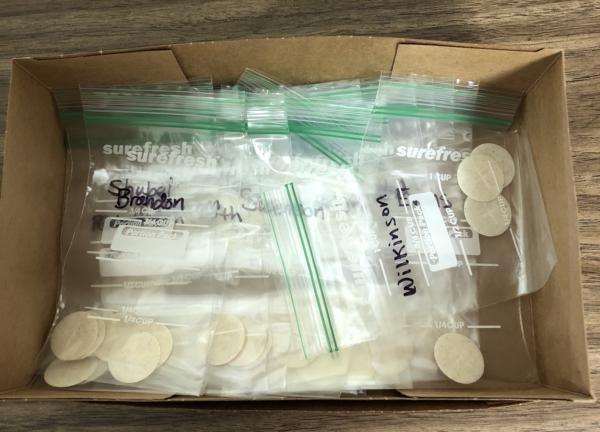

Consecrated host, prepared and packaged with sanitized hands by the Rev. David Kendrick, awaits delivery to parishioners. Photo: David Kendrick

With temporary approval from Field, Kendrick told parishioners the Communion from the March 29 service would be available upon request. Kendrick, following sanitization procedures, placed individual wafers in sealed plastic bags midweek for doorstep delivery on April 4 to parishioners who had asked for them. Then they were encouraged to receive that Communion during St. John’s online Palm Sunday service, as Kendrick and the organist celebrated Eucharist with new wafers. Some of the Palm Sunday Communion — as well as consecrated wine — will be distributed to parishioners this week for Easter.

“It’s a similar situation to when I take Communion to someone who’s shut in,” Kendrick said.

The bishop of the Diocese of West Missouri has authorized the Rev. David Kendrick to deliver the Eucharist to parishioners through Easter. Photo: David Kendrick

While Kendrick is celebrating the Eucharist with the church organist present, some have asked whether a priest can celebrate alone in a church while the congregation watches on a livestream, to prevent any risk of disease transmission. Again, the current Book of Common Prayer has no specific prohibition against this, although the wording of the rite (in which “the People” are an integral part of the service) implies that the Eucharist is inherently a communal act.

This point, too, draws differing interpretations. Roman Catholic priests are allowed to celebrate Mass alone if there is a good reason to do so, such as illness. The Church of England still officially uses the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which does explicitly require the presence of at least three people for Communion. However, on March 31, the Diocese of London announced that if priests cannot have anyone else present, they are permitted to celebrate with people attending via livestream for as long as the current physical distancing restrictions are in effect.

But if priests celebrate the Eucharist with congregants watching online, have the people actually received the sacrament? If they have bread and wine in front of them at home, could the priest consecrate them remotely?

That was a hypothetical considered by the Rev. Liz Hendrick, rector of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Snellville, Georgia, which canceled in-person services on March 14. To continue celebrating Communion, church leaders first considered an approach similar to that of St. John’s in Missouri: Wafers would be consecrated and placed in Ziploc bags that parishioners could come and take home. But with so much still unknown about the virus, they realized they could not guarantee parishioners’ safety.

“And then I thought about the idea of doing Communion-in-place,” Hendrick told ENS. She or the associate rector would celebrate the Eucharist via livestream, and parishioners would have bread and wine (or juice) ready at home.

“And as we came to the consecration, people at home could hold up bread or could hold up wine, and that it would be consecrated … that it would somehow become the body and blood of Christ, as it would have if it was on the altar.

“The rubrics of the church say that you really can’t do that, when you look at the instructions – that it is a custom in the church that [the bread and wine] be touched. And for that reason, and also because of a conversation that I had with my bishop, I wanted to rethink that,” she said.

Hendrick looked for a way to re-create the sense of community people find in the sharing of the Eucharist without trying to have the sacrament itself.

“The sacraments that we do in the church are always done in community,” Hendrick said. “And that community is the one that … sees the sharing of Christ’s body and blood as being a corporate event and not an individual one.”

And many of the livestream services from other churches that she saw “didn’t really strike me as community. It struck me as a few representatives of community,” she said. “Watching a few people receive while everyone else at home watched – it wasn’t anything that resonated with me.”

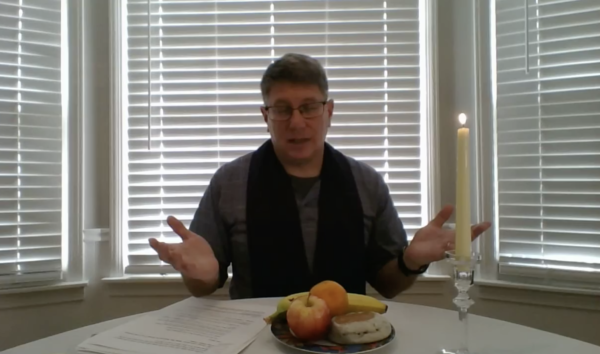

The Rev. Tommy Matthews, associate rector of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Snellville, Georgia, celebrates an agape meal with parishioners via livestream on March 22, 2020. Image: St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church

The practice St. Matthew’s settled on is called an agape meal (from the Greek term for unconditional love). Parishioners are invited to decorate their tables at home and prepare a meal. An ante-communion service is livestreamed (essentially the Eucharistic rite without the Eucharist itself) and then the meal is blessed – not consecrated – and shared.

“That is a way of pulling us together around the breaking of bread and the sharing of fellowship. It may not be a sacramental sharing of food, but it’s a blessed sharing of food,” she said.

In solidarity with her parishioners who cannot receive the Eucharist, she and the associate rector will not celebrate it until they can all be together again, instead opting for the Daily Office and other services.

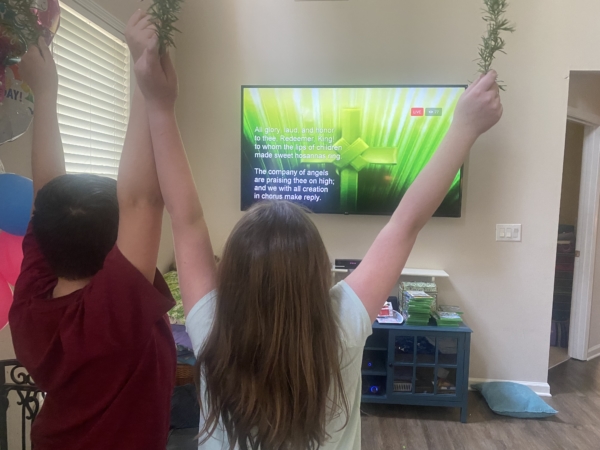

Young parishioners of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church participate in a Palm Sunday livestream service on April 5, 2020. Photo: Amanda Livermont

Some have pointed out that this is familiar territory for The Episcopal Church. Episcopalians’ common practice of celebrating the Eucharist and receiving Communion every Sunday is a relatively new development in the history of church, beginning in the liturgical renewal movements of the mid-20th century. The shift was seen as a return to Christian roots of the first centuries of Christianity, when Jesus’ early disciples would regularly receive the bread and wine together in remembrance of his death and resurrection.

Christian practice gradually shifted away from such regularity, so that by the 16th century, when reformers tried encouraging worshippers to receive Communion weekly, they found little success. It had become common to receive Communion just once a year at Easter – if at all, according to the Rev. Ruth Meyers, dean of academic affairs and professor of liturgics at Church Divinity School of the Pacific. Many Christians were content simply to look at the bread and wine and feel a spiritual connection without receiving, possibly because they didn’t feel worthy.

A new reform movement finally began to change worship habits in the 1950s. The Roman Catholic Church notably adopted changes in that direction recommended by its Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s, and in The Episcopal Church, grassroots efforts to increase the frequency of the Eucharist influenced the church’s 1979 Book of Common Prayer. Among the additions in that prayer book revision was language specifying that Holy Eucharist is “the principal act of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day and other major feasts.”

“The way that we have inherited and understood Eucharistic celebration is that this is a community that gathers with bread and wine and together gives thanks for this bread and this wine in this place,” Meyers told ENS.

Haynes, bishop of Southern Virginia, shares the view that the physical presence of the community is a crucial component of the Eucharist, and well-intentioned efforts to celebrate it in other ways may miss the point.

“We are an incarnate faith. We are a bodily faith. God made our bodies; he deemed them good. So he likes them. And he thought our bodies were good enough for his son to come and dwell in one, and to share our human experience in a body. None of that was done virtually,” Haynes said.

At the same time, Meyers cautioned that some of the efforts to bridge physical separation and continue receiving Communion may be too narrowly focused.

“It has an undue emphasis on the actual reception of the elements, without looking at the totality of the celebration, which includes not just receiving the elements but that great prayer of thanksgiving,” Meyers said.

Haynes agreed, pointing to a practice that churches in her diocese and others have begun adopting: celebrating the Eucharist on livestream, displaying the consecrated bread and wine on the altar, and having the congregation at home pray the Prayer of Spiritual Communion attributed to St. Alphonsus, which expresses a desire to receive the spiritual benefits of Communion when it cannot be received in physical form.

“I believe very strongly that if we truly want the body and blood of Jesus, we will receive the benefits of that even though we can’t consume it physically,” Haynes said. This concept is put forth in the rite of Ministration to the Sick in the Book of Common Prayer, which specifies that the benefits of Communion are received even if the bread and wine cannot be consumed.

There is a similar reference in the Armed Forces Prayer Book, Meyers said.

“Theologically, it’s saying that, really, the benefit comes not just from receiving the sacrament but from the work of Christ with his incarnation and life and death and resurrection,” Meyers told ENS. “Spiritual communion is a way of connecting with the tangible element of bread and wine that we don’t have tangibly.”

Haynes also encouraged Episcopalians to look beyond the familiar rituals they miss and see that encounters with God happen in other ways.

“I miss not being able to receive the Eucharist, but I do think that Christ is revealed to us in other ways as well, like through the Word and through acts of kindness to people that are marginalized,” she said. “And maybe God is using this time to remind us that there are other ways to encounter his son.”

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org. David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu