Episcopalians face challenges to help the hungry during pandemicPosted Mar 26, 2020 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] “Hunger doesn’t go into quarantine.”

That’s the reason 4Saints Food Pantry in Fort Worth, Texas, and similar ministries all across The Episcopal Church are coming up with new, safe ways to continue to serve people in their communities who depend on them for food and companionship. 4Saints, a ministry of four parishes all named for saints in the Diocese of Fort Worth’s eastern deanery, served 115 families on a cold and rainy March 20. Each client who drove through the parking lot of St. Luke’s in the Meadow got a bag of canned goods, canned and fresh meat, milk or juice, a carton of eggs and cereal. Families could also request diapers.

“Hunger doesn’t go into quarantine,” Katie Sherrod, the Fort Worth diocese’s communications director and a member of St. Luke’s, wrote to Episcopal News Service in a Facebook message.

The challenge is finding safe ways to provide food while adhering to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s physical distancing guidelines. Most dioceses have issued guidelines for the work.

In addition, older volunteers who are the backbone of many outreach ministries are among those considered most vulnerable to COVID-19.

“Our primary volunteer force is retired people,” said Linda Curtiss, director of the Bradley Beach Food Pantry housed at St. James Episcopal Church in Bradley Beach, New Jersey, on the Jersey Shore. “Most of our volunteers who can’t come anymore have said it’s because their families have told them, ‘Please don’t.’”

Judy Staggard, a longtime volunteer at the Bradley Beach Food Pantry at St. James Episcopal Church in the New Jersey shore town, moves a crate of food into place March 24 so other volunteers can load up more bags for the pantry’s clients. Photo: Linda Curtiss

The pantry is not alone in its dependence on older volunteers. Lay leaders in the Diocese of New Jersey who participated in a video conference in support of outreach ministries on March 20 repeatedly returned to the issue. The participants discussed whether high school and college students, now home because of school closings, might be recruited to bridge the volunteer gap.

Curtiss is grateful that new volunteers have offered to help because she expects that, for the foreseeable future, “people who thought they could volunteer this week decide they can’t come next week, and that’s even if they don’t get sick,” she told ENS by phone.

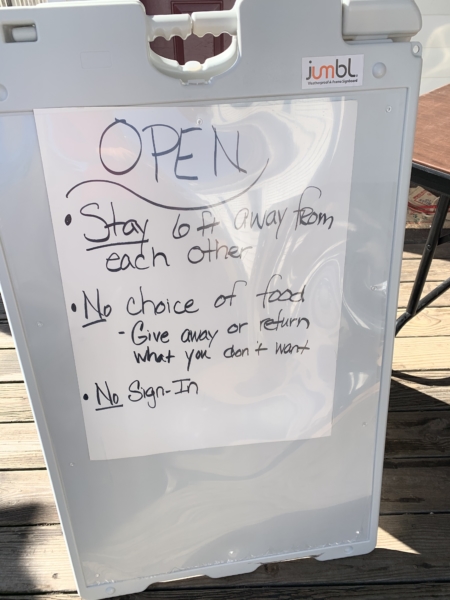

A sign outside the Bradley Beach Food Pantry on March 24 outlines the new reality brought on by COVID-19 restrictions. Photo: Linda Curtiss

Curtiss spent the latter part of last week redesigning the pantry’s operation to limit the exposure of clients and volunteers to each other. The pantry will now only distribute prepacked bags, rather than allowing people to request items. When the pantry is closed, volunteers pack bags alone or in pairs while maintaining their distance. Others restock shelves when baggers are not present. The move to pre-bagging means fewer volunteers are needed when the pantry is open from 10 a.m. to noon Monday to Friday and 6 p.m. to 7 p.m. on Thursday.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=9″”]The Episcopal Church’s Washington, D.C.-based Office of Government Relations supports the stimulus bill in response to the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis. To learn more about how you can offer your support, click here.[/perfectpullquote]

Across the church, feeding ministries small and large are adapting. For instance, on March 25, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Marquette, Michigan, turned its monthly community dine-in meal that typically serves 20-30 people into to-go food bags available for pickup at the church during the meal’s usual time. “We just hope it doesn’t snow,” organizer Mary Sullivan told ENS in an email earlier in the day.

Volunteers are packing the bags at home, adhering to a specific protocol, and dropping them at the church, according to Kathy Binoniemi, communications coordinator for the Diocese of Northern Michigan and a St. Paul’s member. The baggers can also slip in a bar of antibacterial soap and a prayer note, Sullivan said.

When the parish asked members to help by contributing from a specific list of canned goods and prepackaged items, Binoniemi told ENS via email March 20, it received more than was needed. Leftovers will be given to a local group working to get food to children who are home because schools are closed.

In the Finger Lakes region of New York, St. John’s in Catharine has the Barnie Parker Sharing Shed stocked with boxed foods, adult diapers and feminine hygiene and cleaning products. The shed is open around the clock, and people can take what they need.

It’s also grab-and-go in New York at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen, just on a much larger scale. The second-largest feeding program in the United States, the soup kitchen typically serves about 1,200 people a sit-down meal in the nave of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Manhattan. It served 7,083 meals during the first two weeks of March, the ministry said on its Facebook page.

At least until April 3, the meal has become a bagged lunch available between 10:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. in the church’s front courtyard. Its weekly Backpack Pantry will also operate from the courtyard on Thursdays. The soup kitchen has suspended its large volunteer program, and staff is distributing food.

In Hawaii, the Waimea Community Meal based at St. James’ Episcopal Church on the Big Island suspended its Thursday community meal on March 19 and will reopen it as a drive-through service on March 26. Volunteers routinely serve a cafeteria-style sit-down meal to as many as 350 people in 90 minutes at an outdoor pavilion on church property.

On March 26, people will get what coordinator Sue Dela Cruz called the ministry’s version of a Japanese bento box, with a hot soup or stew, rice and a dessert. She told ENS in a phone interview on March 23 that she has set up a three-month rotation of menus for the boxes. She’s developed new protocols so that a reduced number of prep and cook volunteers can work at a distance from each other during separate shifts.

Dela Cruz and other feeding program coordinators know that they offer not just food but also social interaction for both volunteers and guests to ease people’s loneliness. The Waimea meal always features live entertainment and gives diners the chance to “talk story,” the traditional Hawaiian way of taking as much time as needed to discuss both the mundane and the profound.

She and the committee that organizes the ministry are trying to come up with a theme for each Thursday’s drive-through “to make it fun for the people coming through and for our volunteers passing out the boxes,” Dela Cruz said.

Everywhere, feeding program ministers are thinking about the future. Back in New Jersey, Derek Minno-Bloom, the director of social justice at Trinity Church in Asbury Park, said about 175 people came to the church’s food pantry on a recent Tuesday. “We gave enough food in one day that normally takes us three days to give away,” he said. “I imagine it’s just going to get bigger.”

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg retired in July as Episcopal News Service’s senior editor and reporter.

Social Menu