Neil Gorsuch’s ‘hero’ uncle was a progressive Episcopal priest on a winding spiritual pathPosted Oct 7, 2019 |

|

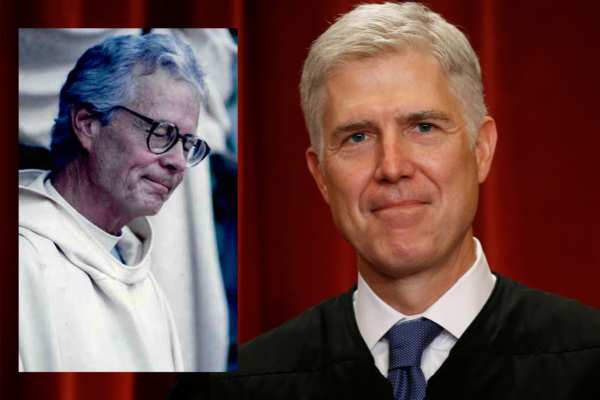

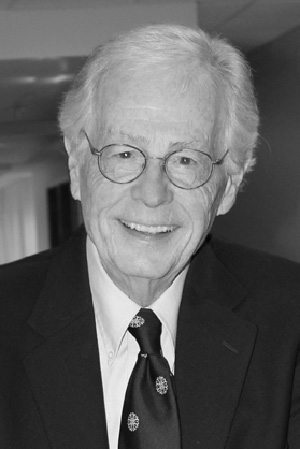

The Rev. Jack Gorsuch, shown at left in a photo from a 2017 memorial service bulletin, was called “a hero of mine” by his nephew, Neil Gorsuch, at his Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Justice Gorsuch is shown in a Reuters photo.

[Episcopal News Service] Facing the 20 U.S. senators who stood between him and a seat on the nation’s highest court, the nominee introduced himself by reading a statement that identified five men as his personal heroes. Four of those men were sitting or former Supreme Court justices. The fifth was an Episcopal priest – the Rev. John Gorsuch, the nominee’s late uncle.

“We recently lost my Uncle Jack, a hero of mine,” Judge Neil Gorsuch said in the 16-minute opening statement of his confirmation hearing on March 20, 2017. Before continuing, he paused to look over his right shoulder at Meg Hopkins, his cousin and Jack Gorsuch’s daughter, who was seated behind him with other family members.

“He gave the benediction when I took an oath as a judge 11 years ago. I confess I was hoping he might offer a similar prayer soon,” Gorsuch said.

Judge Neil Gorsuch reads an opening statement on March 20, 2017, during his Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Photo: White House via video

News articles at the time of Gorsuch’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court noted that he, his wife and their two daughters regularly attended services at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Boulder, Colorado, which The Washington Post described as “a notably liberal church.” Since his confirmation as an associate justice on April 7, 2017, Gorsuch has earned a reputation as a reliable member of the Supreme Court’s conservative bloc.

Gorsuch begins his third full term on the Supreme Court on Oct. 7, but since his nomination, little has been reported about the uncle he remembered fondly at his confirmation hearing. The nephew’s high-profile shoutout only hinted at the breadth of the uncle’s winding 85-year spiritual journey.

“My father was a big, expansive thinker, so within that there was room for a lot,” Hopkins, who lives in Mequon, Wisconsin, said in an interview with Episcopal News Service about her father. “He was a progressive person,” she said, but that created no distance between him and Hopkins’ more conservative cousin.

“Neil and my dad loved each other very much, and it didn’t make any difference what their political views were,” she said.

Jack Gorsuch, who died just a month before his nephew’s confirmation hearing, was a Yale Divinity School graduate and runner-up in 1975 for bishop of the Diocese of Olympia. He led his congregation in Seattle, Washington, through the city’s racial upheaval in the 1970s, championed the ordination of women and later quit parish life to open a spirituality and meditation center with his wife, Beverly Gorsuch, a psychotherapist.

The Rev. Jana Troutman-Miller and the Rev. Jack Gorsuch pose for a photo at an event at St. John’s On The Lake, a retirement community where the two Episcopal priests collaborated on a spirituality group for residents. Photo courtesy of Jana Troutman-Miller

Even in his final years, Jack Gorsuch remained active in religious ministry. Living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, at St. John’s On The Lake, an Episcopal retirement community, Gorsuch partnered with the staff chaplain to start a spirituality group for residents.

“He was just a great guy. He was just very sweet and gentle, had a really great sense of humor,” the Rev. Jana Troutman-Miller, chaplain at St. John’s On The Lake, told ENS. Gorsuch made many friends there in just over two years, she said. “He was just one of those personalities that attracted a lot of people. A lot of those folks went to him for spiritual advice.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch, who declined an interview for this story, recently published a book, “A Republic, If You Can Keep It,” about his judicial philosophy and the importance of civil discourse in American public life. He has avoided speaking publicly about his faith and spiritual background.

“People would view that as me tacitly admitting it has something to do with my day job, and I reject that,” Gorsuch said in an interview with a Wall Street Journal editorial board member. He acknowledged, though, that faith is “a great reservoir of strength for me. I need it, as a person.”

His uncle, on the other hand, left little written record of his political views but spoke openly of his faith – from the pulpit, during contemplative prayer gatherings, at the spiritual development center he co-founded, in written messages to fellow Yale Divinity alumni and in his 1990 book, “An Invitation to the Spiritual Journey.”

The book was a primer on looking inward for God’s presence, but Gorsuch briefly turned his focus outward.

“At our best in contemporary America we are attuned to a spirit of warm generosity and openness of spirit that makes room for great diversity and welcomes the best efforts of all citizens to better themselves. At our worst attunement is wolfish,” Gorsuch wrote. “Each part of the larger whole undertakes only its own gain.”

Parish priest in a time of change

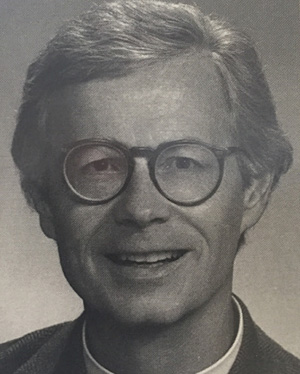

The Rev. Jack Gorsuch is seen in an undated photo from his 17 years as rector of Epiphany Episcopal Church in Seattle, Washington. Photo: Epiphany Episcopal Church

A news article in 1985 described Gorsuch as “a lanky, relaxed father of two.” In portraits at various ages, his appearance is virtually unchanged: round glasses, white clergy collar, his hair parted loosely into a wave, a welcoming smile bubbling from a reservoir of optimism.

Neil Gorsuch, a native of Denver, Colorado, wrote in the introduction to his book that his life’s story “has its roots in the American West.” The same could be said for his uncle.

Jack Gorsuch was born Feb. 1, 1932, in Denver, the oldest of four children. Their father, the elder John Gorsuch, drove a trolley to pay his way through college before opening a law firm. “He cared deeply about his community and he showed it,” Neil Gorsuch wrote of his grandfather. “By his example, he taught me to care about my community, work hard, and make the time we have here count – and to be sure to laugh a lot along the way.”

Jack Gorsuch, older brother of Neil Gorsuch’s father, attended public schools in Denver before moving to Connecticut to attend Wesleyan University. He was president of his fraternity and in 1953 earned a bachelor’s degree in intellectual history. In 1956, he graduated from Yale Divinity and was ordained a priest by Washington Bishop Angus Dun at Washington National Cathedral. Parish work followed, in Washington, D.C., and Kansas.

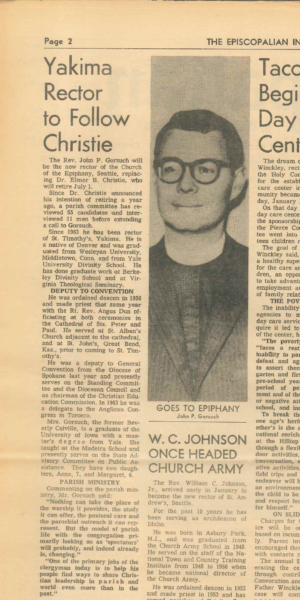

A Diocese of Olympia newsletter features an article about the Rev. Jack Gorsuch being called as rector of Epiphany Episcopal Church in Seattle in 1968. Photo: Diocese of Olympia

In 1963, he was called to serve as rector of St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church in Yakima, Washington, a midsize city southeast of Seattle in the mostly rural Diocese of Spokane, and within a few years he was one of 55 candidates vying for rector at the larger Epiphany Episcopal Church in Seattle’s Madrona neighborhood bordering Lake Washington.

“This is a time when the foundations are shaking all about us,” Gorsuch wrote in a brief essay submitted to Epiphany along with his biographical details, yet parish ministry remained to him an “indispensable tool of God,” specifically for worship, formation, pastoral care and outreach. He added that congregations may need to rethink their claims to a mere “spectator” role in society.

“What about the role of the parish church in revolutionary times like ours?” he continued. “The job of the parish clergyman today, as I see it, is neither to be a milquetoast nor a brash martyr, but, wherever possible, a prophetic spokesman for God and a sensitive servant of people.”

Epiphany welcomed Gorsuch as its new rector at a ceremony in October 1968. The church and priest “were soon venturing into new liturgical, theological and cultural territory,” Barbara Stenson Spaeth, a longtime member of Epiphany, wrote in her 2007 centennial history of the parish. A decade later, she wrote of his influence in a memorial tribute for the church’s newsletter. “The Rev. John P. Gorsuch, witty, innovative and progressive, undoubtedly transformed Madrona’s Epiphany Church, and in significant ways, the wider Episcopal Church in our city and region.”

Epiphany in 1968 lay on the fault line of redlined housing segregation in Seattle, Spaeth told ENS. That divide fueled increasing tensions in the late 1960s and early 1970s between the racially diverse Madrona neighborhood to the south and the primarily white Denny-Blaine neighborhood to the north.

Gorsuch “was, in this community, a leader in civil rights advocacy and racial integration,” Spaeth said. He visited with residents in their homes, listening to white neighbors who felt wary of integration and listening to black neighbors who said they didn’t feel welcomed at Epiphany.

He invited them all to the church.

Gorsuch also oversaw the congregation’s decision to separate from its adjoining private school, which had become a magnet for children from affluent white families who weren’t Epiphany members. He developed connections with the interreligious faith community in Seattle. He rallied the congregation together in the wake of a 1975 arson attack on the church, which luckily sustained little more than smoke damage in the fire.

And on Feb. 3, 1977, he preached at Epiphany during the ordination of the Rev. Laura Fraser, the first female priest in the Diocese of Olympia. The service drew intense media coverage and was remembered as “one of the ‘happenings of the 1970s’” in Seattle, according to the Post-Intelligencer. Fraser had “created a sensation.”

Opponents of women’s ordination held a rival service across town on the same day. At General Convention the previous year, Olympia Bishop Robert Cochrane had voted against the resolution that paved the way for women to become priests, but he still agreed to preside at Fraser’s ordination. More than 50 clergy members from around the country attended, and the service was seen as “a real victory,” one of those priests recalled in 2002.

In championing such issues, Spaeth suggested Gorsuch was ahead of his time. “In his day, in that era, which was so transformative and so full of change for the city, he was definitely on what anyone would call a progressive track,” she said. “The character of the church today, at least in our part of the world, matches what Jack would have wanted.”

‘I took an inward turn’

Later in life, Gorsuch looked back on that time and noted he was growing disillusioned with career ambitions within the church – a “good midlife crisis” brought on by a lost bishop election.

A diocesan publication includes the Rev. Jack Gorsuch’s responses to a questionnaire in 1975 when he was a candidate for bishop of the diocese. Photo: Diocese of Olympia

“Moving into the episcopacy seemed to me like the outcome of a fairly fast run up the church chairs,” he wrote in “An Invitation to the Spiritual Journey.” In 1975, he and Cochrane were finalists to lead the Diocese of Olympia, but Cochrane, then rector of Christ Church in Tacoma and chaplain to the city’s police department, was seen as a more conservative candidate. Cochrane won on the eighth ballot.

The loss was a humbling blow to Gorsuch. His parish, though sympathetic, was glad to have him for a few more years.

“He should have been our bishop, but we are grateful he stayed our rector,” Spaeth told ENS.

Just six months later, he again was a finalist for bishop, this time in the Diocese of Indianapolis, but Gorsuch never made it to the ballot there. One night he dreamed he was being vested in a cope and miter, but they suddenly went up in smoke, revealing a baby bathed in light. He called up the search committee the next day and withdrew from consideration.

“I took an inward turn, and I’ve been on an inner journey ever since,” Gorsuch said years later in a Seattle Post-Intelligencer story. In his book, Gorsuch gave a longer explanation for his inward turn, saying he felt guilty that he was letting his daily routine and personal ambitions distract him from cultivating a deeper relationship with God.

“I was someone who had gotten too busy for God,” he said. “I had taught courses on the spiritual life and prayer in adult education classes with some success, but my own spiritual life was underdeveloped,” he said. He began reading and rereading books by those “who had taken the spiritual journey another step,” from St. Teresa of Avila to Thomas Merton.

By 1981, his spiritual exploration was reflected in a biographical message he wrote for the 25th anniversary of his Yale class. “I’ve gone much deeper into prayer and meditation, and have increasingly found that God is much more than a theological premise or ‘sometime reality,’” he said. “At the same time exciting things are going on in this parish.”

He concluded, “I’m not terribly optimistic about everything that’s happening in the American scene right now, but I am increasingly aware of the grace of God. It’s a tough and glorious time to be alive.”

President Ronald Reagan had just taken office and appointed Gorsuch’s sister-in-law, Anne Gorsuch, as EPA administrator. The job required her to move her family, including her 13-year-old son, Neil Gorsuch, from Colorado to Washington, D.C. The teen’s parents divorced a year later. Anne Gorsuch, shortly after remarrying, resigned from the EPA in 1983 amid a scandal related to her ties to chemical companies.

The year 1983 was pivotal for Jack Gorsuch. He was granted a sabbatical, during which he visited a Benedictine monastery in New Mexico, studied deep meditation at a spiritual community in California and trained as a spiritual director at the Shalem Institute for Spiritual Formation in Washington, D.C.

In his final two years at Epiphany, he was leading two contemplative prayer groups, as well as a “God 202” class for new and returning church members. In 1985, he resigned as rector, and he and Beverly Gorsuch opened the Center for Spiritual Development in rented space on St. Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral’s campus in Seattle.

The Rev. Jack Gorsuch participates in the October 2014 ordination ceremony for the Rev. Jana Troutman-Miller at St. John’s On The Lake in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Photo courtesy of Jana Troutman-Miller

“I think they always defined themselves as Episcopalians,” Hopkins said of her parents, but they became more interested in “helping others in the inner journey” than in their own professional advancement.

The ecumenical, nonprofit spiritual center was “designed to help people explore, deepen and affirm the place of God in their lives without underestimating the challenges along the way,” according to the center’s introductory brochure. For more than five years, the Gorsuches led classes and retreats at the center. In 1991, they handed over the reins to a new executive director, the Rev. Jerry Hanna, a fellow Episcopal priest.

Hanna, now 80, is vicar of St. David Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Shoreline, Washington. In an interview, he said, the center rode the waves of broader trends in American spirituality.

“We were in kind of a descending peak of the New Age movement, which involved a lot of esoteric, and what we could say, semimystical experiences and teachings, so it was really a hotbed of those kinds of spiritualities, which were proliferating all over the country,” Hanna said. He remained at the center for nearly three decades, until it closed this year.

Hanna told ENS he had been trained in the transcendental meditation tradition, while “Jack was a traditionalist, in the sense that he attached himself first to centering prayer and teaching spiritual direction.”

In his forward to Gorsuch’s 1990 book, Gerald May wrote that Gorsuch grounded his spiritual teachings in theology, scripture, psychology and “a realistic appraisal of the graces and confusions of modern daily life.” Gorsuch had studied with May at the Shalem Institute, where May served as spiritual director.

“His journey has inspired mine as I have seen him claim and act upon his desire to seek a deeper and more direct conscious relationship with God, and to help others do the same,” wrote May.

‘More to learn, more to grow’

Gorsuch’s 17 years at Epiphany spanned nearly the entire childhood of his nephew, the future Supreme Court justice, and Neil Gorsuch’s subsequent college years and professional life coincided with his uncle’s spiritual journey beyond The Episcopal Church.

Neil Gorsuch, who was raised in the Roman Catholic Church, earned his bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1988 and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1991. He worked as a law clerk to a federal appeals court judge just as Jack Gorsuch was stepping away from the Center for Spiritual Development.

In 1996, he married Marie Louise Burleston, a British graduate student he had met while working on his doctorate at Oxford University. Louise, as she is known, grew up in the Church of England, and when the Gorsuches returned to the United States together, they became members of Holy Comforter Episcopal Church in Vienna, Virginia, according to a CNN report on Gorsuch’s faith background.

While Neil Gorsuch lived in Virginia and clerked for Supreme Court Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy before venturing into private law practice, Jack and Beverly Gorsuch spent eight years living at an ashram in California focused on East-West spirituality.

Both of Neil Gorsuch’s parents died in the early years of the new century, before he began working for the Department of Justice in 2005. With his parents gone, Gorsuch’s bond with his uncle strengthened, Hopkins said. “Neil and my dad were just personally super close, had just a really sweet, personal relationship,” she said.

Appellate Court Judge Neil Gorsuch reacts to comments made by speakers at a swearing-in ceremony Nov. 20, 2006 in Denver. Also pictured are his daughter, Emma; his wife, Louise; and his uncle, the Rev. Jack Gorsuch. Photo: Ken Papaleo/Rocky Mountain News via Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

On Nov. 20, 2006, when Jack Gorsuch spoke at the swearing-in ceremony in Denver for newly confirmed 10th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Neil Gorsuch, the Denver Post reported the event was “a family affair.”

By then, Jack and Beverly Gorsuch had settled in Bellingham, Washington, to be near their older daughter, Anne Gorsuch, who lived in Vancouver, British Columbia.

“The best way to sum up what’s going on for me at this point is to say I seem to be a guy who is getting clearer about what it means to wake up,” the former parish priest wrote in 2006 for his 50th Yale class anniversary, and he praised his wife as “an incredible partner, insightful and as spiritually intentional as anybody I know.”

In 2014, with Beverly Gorsuch suffering from dementia, she and her husband moved to Milwaukee, where she still lives, just a few miles south of her daughter.

Hopkins said being at St. John’s On The Lake in his final years boosted her father’s spirits. He became fast friends with Troutman-Miller, the chaplain, and participated in her ordination ceremony that October. In 2016, during his final year, they collaborated on a “saging” group, in which 10 or so people gathered to discuss spiritual questions related to aging.

Troutman-Miller said Gorsuch was personally exploring the same questions for himself.

“Being in his 80s, he was very much looking at what comes next and the experience of continual learning and growth that happens after death,” Troutman-Miller said. “He was convinced that it doesn’t just stop, the learning and growth doesn’t just stop with death, but there’s more to learn, more to grow.”

Beverly and Jack Gorsuch are all smiles during a gathering at St. John’s On The Lake, a retirement community where they moved in 2014. Photo: Jana Troutman-Miller

When President Donald Trump announced on Jan. 31, 2017, he was nominating Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, the family greeted the news with pride, and on a group call with family members, “the pastor joked that some of the people on the line were Democrats,” according to CNN.

The nomination became a topic of conversation around St. John’s On The Lake only because residents made the connection between the name making headlines and their friend, the Episcopal priest, Troutman-Miller said. He would hint that his politics didn’t neatly align with his nephew’s politics, but “he was gracious to his nephew,” she said.

The service bulletin from a May 20, 2017, memorial service at Epiphany Episcopal Church in Seattle, Washington, features this undated photo of the Rev. Jack Gorsuch.

Jack Gorsuch, 85, died on Feb. 15, 2017, two weeks after his nephew’s nomination to the Supreme Court. A funeral service was held at St. John’s On The Lake’s chapel, and three months later, in Seattle, Epiphany celebrated Gorsuch’s life in a memorial service. His two daughters and a former clergy colleague gave eulogies.

One of the readings was from Gorsuch’s own book: “The place to start with the spiritual journey, when with the help of trust we move beyond our stuck places, is with ourselves before a God who takes us where and as we are. There is no other place to begin. We are who we are. We are no less and no more farther along the path than at this moment. This is great ‘good news.’”

Hopkins, 57, said her father’s death likely was still fresh on the mind of Neil Gorsuch as he sat one month later for his confirmation hearing, one reason he gave a nod to the uncle in his opening statement.

Jack Gorsuch may not be alive to speak at his nephew’s swearing-in ceremony for the Supreme Court, but “as it is, I know he is smiling,” his nephew said.

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu