Grandma’s songs set overture to Presiding Bishop’s faith journeyPosted Oct 4, 2019 |

|

[Episcopal News Service – Canterbury, U.K.] As a child, Presiding Bishop Michael Curry would listen intently as his grandma sang hymns at the kitchen sink.

Familiar tunes added meaning to holy words. Even in her darkest moments of despair, as her daughter lay dying in the hospital following a brain hemorrhage at 44, Grandma Nellie Strayhorne would sing.

As she prepared dinner for the family, those melodious interludes would sow an important seed for the 14-year-old Curry, feeding his love of music and ultimately influencing his journey along the Jesus Movement.

“That memory of her singing those songs imprinted itself profoundly on me,” Curry told an audience gathered at Canterbury Cathedral’s Clagett Auditorium on Oct. 2. “Thinking about it now, I realize she was singing those songs, cooking food for her grandchildren and her son-in-law, while her own daughter was in a coma. … [I thought] any woman who has figured out how to do that in that set of circumstances knows something that I want to know about this Gospel, this Jesus, about this God.”

Curry later told ENS that the power of music is multilayered, and these particular songs in the midst of sorrow were clearly meditative. They brought healing and strength, not just for grandma, but for the whole family.

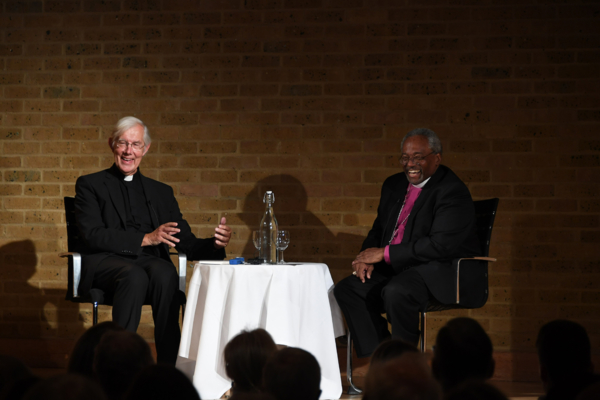

The Very Rev. Robert Willis, dean of Canterbury Cathedral, hosts Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry for an Oct. 2 conversation about the importance of music and the songs his grandma sang. Photo: Adrian Smith/Canterbury Cathedral

Invoking a West African saying, “Without a song, the Gods will not descend,” Curry told his Canterbury audience, “There’s something about song that speaks on multivalent levels in us. And sometimes the song, the hymn, can reach down in crevasses deep down inside of us, that words by themselves don’t necessarily reach. … It has the power to evoke something. It is like some music can speak to the soul.”

The Very Rev. Robert Willis, dean of Canterbury Cathedral and a music composer, hosted the conversation with Curry. He pointed out that the sermons you remember “are few and far between, but the hymns are actually embedded in your head and heart.”

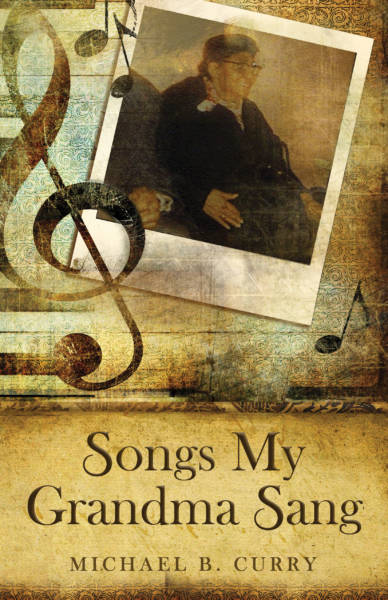

Following the success of Curry’s book “Crazy Christians,” Church Publishing Inc. encouraged the presiding bishop to write another. CPI’s Vice President for Editorial Nancy Bryan told Curry she had noticed that whenever he preached he would often quote a hymn. “When I looked back at my sermons, I realized there was a pattern to them, and many of the hymns I was quoting were actually the hymns that grandma used to sing,” Curry said.

Following the success of Curry’s book “Crazy Christians,” Church Publishing Inc. encouraged the presiding bishop to write another. CPI’s Vice President for Editorial Nancy Bryan told Curry she had noticed that whenever he preached he would often quote a hymn. “When I looked back at my sermons, I realized there was a pattern to them, and many of the hymns I was quoting were actually the hymns that grandma used to sing,” Curry said.

This realization led to the 2015 publication of “Songs My Grandma Sang,” which provided the theme for the Canterbury event.

Many of the hymns Curry references in his book – such as “Just As I Am,” “Amazing Grace,” “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” “I’m So Glad Jesus Lifted Me,” “I Come to the Garden Alone” – had been an integral part of U.S. culture, particularly in the southern states.

Curry’s father was an Episcopal priest and his grandma was a “rock-ribbed” Baptist, “so I grew up with those two very different worlds in one sense, but at their deeper level very similar, and that has formed me as much as anything,” Curry said.

Growing up in Buffalo, New York, Curry said that his father was active in the civil rights movement and remembers a series of meetings with black preachers of various denominations that he later realized had been the planning for the buses that would transport them to join the March on Washington in 1963.

“So I grew up in this world that was really about making the world and life something closer to God’s vision and God’s dream for all of us,” he said.

The songs and sayings that pervaded the lives of Curry’s grandma and her generation – who lived through the Jim Crow years of enforced racial segregation – “reflected a deep faith and profound wisdom that taught them how to shout ‘glory’ while cooking in ‘sorrow’s kitchen,’ as they used to say,” Curry writes in the first chapter. “In this there was a hidden treasure that saw many of them through, and that is now a spiritual inheritance for those of us who have come after them. That treasure was a sung faith expressing a way of being in relationship with the living God of Jesus that was real, energizing, sustaining, loving, liberating, and life-giving.”

Curry recalled hearing Andrew Young Jr., a leader in the civil rights movement and a close confidant to Martin Luther King Jr., say that there would have been no movement had they not had songs. “What I think he was saying was that something had to keep people marching when they were scared to death,” Curry said. “It’s sort of like a mantra, something that you can keep singing, that can keep you focused and then you can handle whatever is coming at you. … When cultures stop singing, something is missing.”

Willis acknowledged that “Amazing Grace,” with text by English priest and abolitionist John Newton, is one of the few hymns or songs that is widely known throughout the Anglican Communion. But he recently learned that the text of the final verse, which begins, “When we’ve been there ten thousand years, Bright shining like the sun,” actually came from the United States, around the time of the American Civil War. According to sources, the verse was written by American abolitionist and author Harriet Beecher Stowe. “It was written as a verse of hope … but it’s a nice thing to think that the two cultures came together in that one hymn,” Willis said.

Even in the most tragic circumstances, music has the power to uplift and regenerate.

Curry remembers reading a speech from the director of the New England Conservatory of Music, who told his freshman students not to think about music as a frivolous add-on to life. The music director was in New York when 9/11 happened and said he saw a city silenced. “The first sign of life was when the symphony [orchestra] played music and people sang,” Curry quoted him as saying. “Don’t think music is a frivolous thing. It speaks to the soul.”

Similarly, Willis said he was moved by seeing people singing and lighting candles in Paris as Notre Dame was ablaze.

The Canterbury event marked the first time Curry had been invited to speak publicly about his book, “Songs My Grandma Sang.” He told ENS that it was a special moment to be able to reflect on his grandmother’s indomitable faith and profound influence that paved his pathway toward ordination.

The Very Rev. Robert Willis, dean of Canterbury Cathedral, hosts Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry for an Oct. 2 conversation about the importance of music and the songs his grandma sang. Photo: Adrian Smith/Canterbury Cathedral

Following his royal wedding sermon that was watched by 1.9 billion people, Curry confessed that his grandma had been in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. “She was there in the room singing hymns. I could hear her voice in the back. She was saying: ‘I gotta see this, I gotta see this.’”

As he reflected further on her life, Curry shared that during a very difficult time in college when he was pursuing a path toward political advocacy, his grandma’s face appeared, and that started his discernment for the priesthood. He started to read some of the writings of Martin Luther King Jr. and “that’s when it all began to crystallize,” Curry said. “Well, if you want to have an impact on the world where we live, maybe your way is to become a priest.”

Although Curry’s grandma didn’t live to see him ordained, she knew he was in seminary. Curry said that when she found out, she joked, “Now Baptist preachers ain’t get the call; they start preaching. How come you’ve got to go to school?”

– Matthew MacDonald is associate editor of the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu