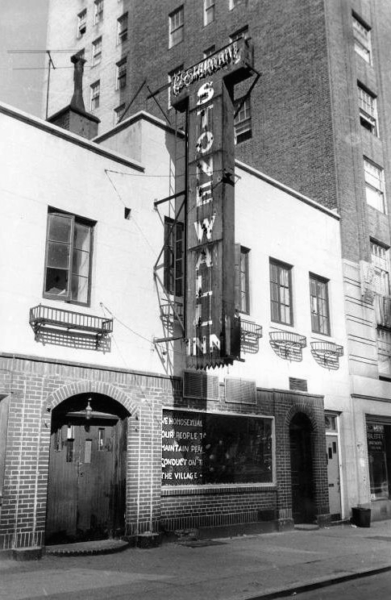

‘God’s bringing us into wholeness’: LGBTQ Episcopalians who witnessed the Stonewall uprising share their storiesPosted Sep 23, 2019 |

|

The Stonewall Inn on Pride weekend in 2016, the day after President Barack Obama designated it the Stonewall National Monument. Photo: Rhododendrites via Creative Commons

[Episcopal News Service] In the summer of 1969, homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association, sodomy was a felony in 49 states, there had never been an openly queer elected official in the United States and there were divisions in The Episcopal Church about whether homosexuality was sinful.

Fifty years later, same-sex marriage is legal across the country, queer politicians serve in both houses of Congress, a gay man is running for president and The Episcopal Church has gay and lesbian bishops. The radical shift in American society’s acceptance of queer people started with a jolt on June 28, 1969, when patrons at the Stonewall Inn, a queer bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, rioted in response to a police raid. At the time, these raids were common; the city was determined to shut down the bars and simply serving alcohol to homosexuals was prohibited.

Although The Episcopal Church has long been a champion of LGBTQ rights and many in the church during the 1960s were ahead of their time in accepting homosexuality, the church did not explicitly express support for gay people until 1976 and did not ordain openly gay people until 1994.

In light of the 50th anniversary of the riots this summer, Episcopal News Service spoke to three queer Episcopalians who witnessed the Stonewall uprising and asked them what it was like, how things have changed and how it affected their faith.

The Rev. John Moody, now 93, was a priest at Trinity Church Wall Street, running a popular arts programming series, at the time of the riots. Frank Tedeschi, now 74, was a graduate student at Columbia University attending the Church of St. Luke in the Fields, two blocks from Stonewall, and later had a career in The Episcopal Church’s Office of Communication and Church Publishing, Inc. Phyllis Jenkins, now 89, was a psychiatric nurse practitioner teaching at Lehman College who attended St. Luke’s later in life and has lived in the same apartment in Greenwich Village for 60 years.

These interviews have been condensed for clarity and concision.

Had you been to Stonewall before the riots?

Phyllis Jenkins: I didn’t hang out in Stonewall because it was a boys’ bar (laughs). And they had girls’ bars! But I was known there, yeah.

John Moody: I’d been to Stonewall, but not often. It wasn’t a bar I went to. It was a younger group. When I moved to the city, I was 44 already.

Frank Tedeschi: I was not there the first night of the riots. I was there two nights before. I was in the Stonewall with a friend whom I knew from graduate school, Arnold Willens. … We knew, and I think my friend Arnold maybe even said, you know, we’ve got to be careful we don’t get raided, something like that. I remember coming up from Grand Street three nights later and somebody said, “They raided the Stonewall last night.”

Had you experienced raids before?

PJ: Oh, yeah. Sure. I remember, there was a bar – I think it was on Eighth Street, I think its name was Mary’s. And there used to be dancing in there. And [when the police came] they’d flash the lights and then you’d change partners; you would choose an opposite-sex partner. For some reason, they went after mostly the boys. They’d give women a warning sort of thing, and off you would go, if you kept your mouth shut. There was an unwritten rule that you had to have on two or three pieces of clothing that identified with your birth sex – you couldn’t be in drag, in other words, in a bar. I most frequently wore – back in those days I was wearing men’s clothes. Not just tailored clothes, but men’s clothes. So yeah, I would get hassled about that.

What was your experience at Stonewall like?

PJ: I went out from home to pick up a Times. And as I approached Christopher Street, I saw a, for lack of a better word, melee. And I am not keen on crowds, but I circulated around the edges. And when I found out what was happening, then I joined. I didn’t stay too long because it was after midnight, and I had to work the next day.

JM: That night, I was getting off a bus in Greenwich Village. I was out on Fire Island and came in on Saturday night because I had Sunday duty. And I looked up – it was only about a half a block from Stonewall. I looked up the street and the lights were all on there, so I knew something was going on. And it was only after, the next day, that I found out what was happening. I went over there several times during the next couple of weeks when there were demonstrations every night. Different groups would have occasions to protest, and so I went up and would talk to people. You would talk about the situation in gay bars, how people felt about their own freedom to go there without police interference. Once it was over, the couple of weeks and riots and whatnot, that kind of a reaction by the police – going into a bar and checking ages and stuff like that – that was called off. So, the atmosphere was much more relaxed.

FT: There was a sense of illicitness, outside-the-norm experience, if not behavior, to be in a place like Stonewall. Because everybody, I realize now as I look back, was – whether he or she realized it or not – had an alert mechanism there. What to do if the cops come or whatever. Just up the street … there was a bar, I think it may have been called the Hornet or something like that. And it was, and still is, a very long room, long and narrow. My friend took me there as well. He pointed me to the back. He said, “Let’s go look at this.” And there was a trellis, and it was dark, and we walked back. And it was full of men. … The music was quiet and slow, and they were dancing, cheek to cheek, as partners. And I can remember that to this day. And this was just up the street from Stonewall. And I don’t think they were ever raided because I think Stonewall paved the way. But just seeing same-sex couples dancing romantically was an eye-opener for me. And I’m telling you this because that experience is just as emblazoned on my memory as Stonewall. But when we were there, we all had our alert mechanisms on. Don’t have your back to the door.

Did you realize it was a historic moment at the time?

JM: Oh, I think afterward. But yes, you did realize it was a historic moment. Because the police were confronted. And it wasn’t long after that the mayor decided that they would not do that anymore.

PJ: Yes, I did. I didn’t know how big, but I knew that we were making history. I did know that.

FT: Oh, no, not at all. That’s one thing I have reflected upon in this anniversary year. I said to myself, “Jeez, who’d have thunk?”

Were you out then?

JM: I was not what you would call “out.” My boss knew I was gay, but there was no connection with the church as such. Soon after that, there was Integrity, which started to meet over at St. Luke’s Church on Hudson. So, I wouldn’t say that I was out, no. I mean, I would go to bars; I wanted to meet people. I wanted to do something about my own sexuality. … I realized celibacy was not a calling for me. And I wanted to, if I could, I wanted to meet someone. And in those days, the way you met someone was at a bar. I didn’t feel as though it would be appropriate to come out at that time because the separation of sexuality and the church – and particularly priesthood – was so officially separate at that time, that I didn’t feel as though that would be appropriate. By the grace of God, somehow I felt all right about being gay, and by that, I mean my own spiritual realization was such that this was who I was. So, the church was not supportive at that time. Spiritually I felt all right with it. I remember being at a bar once and a young man asking me what I did. I said I was a priest. And he said, “Well, how can you possibly be here?” I said, “Well, what is that really saying about sexuality? If I didn’t feel all right about being here, I wouldn’t be here.” But there was such a feeling of cultural oppression in that time, that people felt very bad about themselves that they were gay.

PJ: Uh… 99.5 percent (laughs). Yeah. I felt that I did not like to discuss my sexuality with people – to be accepted. You know, I didn’t go around asking people what they did and they shouldn’t go around asking me what I did. But yeah, I was never one to hide, but I was never one to throw it in your face either. Especially after I started going back to school. My livelihood depended on the establishment.

FT: Yes and no and no and yes. It’s what one chooses. Everyone was welcome at St. Luke’s, and I know other churches as well. But sexuality wasn’t talked about. Certainly not homiletically. Now, of course, it’s quite a different story.

Did your experience witnessing the start of the gay liberation movement impact your faith at all?

JM: Oh, absolutely. Oh sure. Yeah. By the grace of God, I believe God wanted to bring me into wholeness with the person I am and the person He loves. And that fed right into and was really strengthened by the gay liberation movement. But the gay liberation movement so often was angry at the church. Angry at their own self-division. And I think it’s the healing of that, in God’s bringing us into wholeness, that will enable us to work for the kind of justice in the world that Jesus calls us to.

PJ: It probably did. I didn’t think of it at that time, but it probably did because I became more aware of other faiths, for one thing. By the time I got to be a preteen, I was annoyed with church in general, religion in general. There was no place for women, blacks or whatever. And my belief faltered, so I just stopped going. And that lasted for 44 years. But I wanted to get my first great-grandchild baptized. … St. Luke’s was around the corner. And I’d been in the church a little, but I went in one day on my way home from work. That was 33 years ago. It’s an easy place to get involved, and I like what their mission is. I like what they do.

FT: Back then, my own faith journey and experience of Sunday morning was kind of a different chapter, separate. And I think in my own psychospiritual development over the past half-century, I’m a much more integrated person than I was and so many other young gay men my age were in those days. We were in our 20s. I was 24 at the raid and I’m now 74. … But I realized that, you know, gay men my age, at that time, we’re accustomed to being below the radar, keeping our heads down, if you will. … I look back and realize that if you’re used to being in the shadows, or subject to name-calling or persecution, you kept a low profile. When those courageous groups of people “…, hell no,” I realize now through the lens of history and of my own life is they were pioneers, they were indeed role models. They said no, no more. And again, from this distance, a half-century later, I respect them for that and I thank them for it.

Has the church overcome its hostility toward the LGBTQ community?

JM: I don’t think it has everywhere. I think in, for instance, my own parish, Trinity Wall Street, yes. I think they’ve overcome that. But whether all the membership has or not, I don’t know. I don’t think so. I think officially, it has overcome it. There are gay and lesbian married priests. And they seem to be accepted. But whether people themselves accept gayness, I’m not sure.

PJ: I think the Diocese of New York has, to a large extent, but not all dioceses are the same. And our diocese is not the same all the way through. But of all of the organized religions, the mainstream religions I know of, I think that The Episcopal Church has the best stance. Publicly, at least, anyway.

FT: Well, you use words like “the church” – what was I reading about the bishop of Albany and other bishops and other congregations who say “no, this is not OK.” … There’s still dissent, there’s still disagreement. And I think we would be shortsighted if we did not admit and acknowledge that.

Should the church be doing more to affirm and protect queer people?

JM: Well, I’d like to see the church really live its inclusivity, where there are no others, we are all one in God! And we as Christians need to share this with all the great leaders and mystical believers in all the major faiths. And the more we’re able to do that, the more I think we see the power of Jesus at work in the world. And I think our presiding bishop is doing that in his gospel of Love. That’s what it’s about!

FT: I think the church has been very good witness for the past 20 years and more. But if we were to do anything more, or in addition, it would be, I think, educationally. … I guess maybe what I mean by education is if there can be more and more opportunity for dialogue.

Is there a particular social issue experiencing a turning point today that you think is analogous to the Stonewall uprising?

JM: Oh, I think so. I think we’re finally realizing the depth and breadth and scope of racial prejudice because of our history of slavery. This is the kind of turning point for that, I think. … I think we have a lot of digging to do on that one.

PJ: No, not really. The last time I really felt a huge involvement was during the plague – during the AIDS epidemic. I worked with people living with HIV, and that was the last time I felt that there was that much involvement by more than a small group of people. … I believe in youth, I believe the youth will be our savior. And we need to concentrate on doing what we can with and for them. And so anything that focuses on young people, I’m for it – particularly young people of color and gay or both.

FT: No, other than the fact that the acknowledgment of same-sex relationships, including matrimony, is not shrinking. It’s doing exactly the opposite. It’s growing. And it’s bearing witness, and it’s causing great joy – and increasing discomfort among those who don’t agree with it.

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu