Episcopal task force educates New Yorkers on what’s at stake in decriminalizing prostitutionPosted Aug 6, 2019 |

|

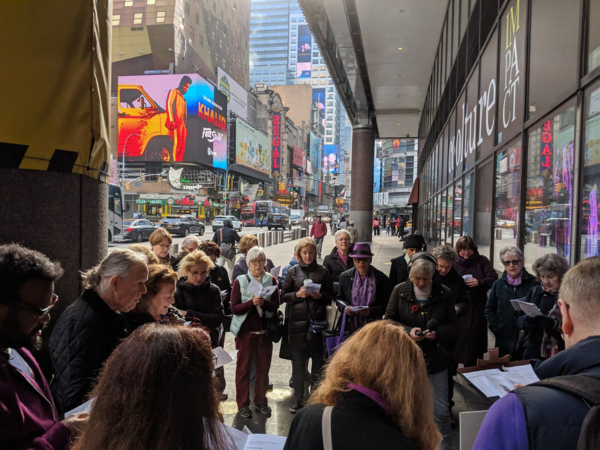

The Port Authority Bus Terminal served as the first station on April 6, 2019, for Stations of the Cross for Sex Trafficking Survivors, an event of the Episcopal Diocese of New York Task Force Against Human Trafficking. The task force is now working to educate the public on a bill introduced in the New York State Assembly that would decriminalize prostitution. Photo: Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] At least three U.S. states and the District of Columbia have introduced legislation that would decriminalize the buying and selling of sex, forcing a long-simmering debate on prostitution into the national dialogue.

Legalization proponents, religious or not, often cite biblical references to prostitution dating back to ancient Israel, telling the Genesis story of Judah and Tamar, and falling back on the well-worn phrase, the “world’s oldest profession.” Opponents tend to argue the “profession” leads to an increase in violence against women and girls and reflects men’s power over women.

“I consider prostitution not the oldest profession, but the oldest oppression,” said the Rev. Adrian Dannhauser, a longtime sex and labor trafficking victims’ rights advocate who leads the Episcopal Diocese of New York’s Task Force Against Human Trafficking. “I think this decriminalization issue is a backlash against women’s rights and progress we’ve made in terms of equality. It’s a power issue and an entitlement issue.”

In late June, at the close of the New York State General Assembly’s 2019 legislative session, three New York City lawmakers introduced a bill that would decriminalize prostitution and legalize the sale of consensual sex. Massachusetts, Maine and Washington, D.C., have introduced similar bills.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]During Lent, the Episcopal Diocese of New York Task Force Against Human Trafficking led a Stations of the Cross for Sex Trafficking Survivors event in New York City. [/perfectpullquote]

Writing in the summer 2019 issue of The Episcopal New Yorker, Dannhauser said: “Sex workers’ rights organizations claim that consenting adults should be allowed to do whatever they want with their own bodies – ‘my body, my choice.’ But in most cases, prostitution is more aptly described as ‘my body, his choice.’ It’s not sexual liberation but sexual exploitation. According to Sanctuary for Families, New York’s leading service provider and advocate for survivors of gender violence, 90% of people in prostitution in the U.S. are trafficking victims. This means that only 10% of prostituted people have any real choice in what happens to their bodies in the sex trade.”

Both sides find common ground in calling for the decriminalization of people bought and sold in the commercial sex industry and for the ability of trafficking survivors to vacate their convictions. Opponents of the decriminalization of prostitution typically favor an “equality” model that focuses more on decreasing demand and preventing exploitation, similar to those adopted in Nordic countries, where cultural attitudes have shifted and it’s becoming no longer socially acceptable to purchase people for sex and it’s seen as a barrier to gender equality.

In the United States, the decriminalization conversation has shifted in the context of the #MeToo movement; alongside an awareness of sexual violence on college campuses; and amid the backdrop of high-profile sex crime cases, like those involving New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft, who allegedly paid for sexual services at a Florida massage parlor, and financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, who stands accused of trafficking underage girls and paying them to perform sex acts.

“It’s not about legislating morality, it’s about social context,” said Dannhauser, in an interview with Episcopal News Service in her office at the Church of the Incarnation on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. “It’s a backlash against women’s rights, and it’s an empowerment and entitlement issue … the whole idea of rape culture on college campuses. “It’s finally coming into the light.”

In late July, the Church of the Incarnation, where Dannhauser serves as associate rector, hosted a Tuesday evening panel discussion to educate the public on the bill. As the Episcopal church’s sanctuary filled with some men but mostly women from diverse backgrounds, a small group of bill supporters gathered in protest on the sidewalk outside, as police officers stood watch nearby.

The four-person panel of opponents – two sex trafficking survivors, an activist and educator, and an activist lawyer – shared personal stories and talked about the bill’s specifics. New York Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, a bill co-sponsor whose district includes Incarnation, had agreed to participate but later rescinded saying the venue wasn’t “neutral.” Toward the end of the event, the protesters from outside entered the sanctuary and disrupted the gathering.

Legalization advocates say that decriminalization would protect people who “do sexual labor by choice, circumstance, coercion,” and they call for legislation that would protect people in the sex trade from economic exploitation and interpersonal violence. They also call for people imprisoned on sex-trade related offenses to be freed and for the de-stigmatization of the sex trade.

Bill opponents, however, say it would thwart prosecution of sex and child traffickers, pimps who prostitute children and pimping in general; permit pimping of anyone 18 years of age or older; allow traffickers to vacate convictions; inhibit prosecutors’ trafficking investigations; and make it harder for law enforcement to identify victims. They are also concerned that the bill would legalize the purchase of sex, brothels and commercial sex establishments, and encourage sex tourism.

“We [New York residents] have to ask ourselves, Why do we need people buying sex? What is that all about?” said Yvonne O’Neal, a task force member. “Personally – and it does keep me up at night sometimes – I’m wondering when I go to church on Sunday, as a person of faith, as an Episcopalian, and I look around in the congregation, my question is, Who are these men that are buying sex? And obviously, they have to be some of them sitting in the pews. Who are they? We don’t know, and why is that necessary?”

Proponents of decriminalization say that “if we need to,” people should be able to sell their bodies, and that legalization will lead to safer working conditions and industry regulations. Opponents say it will lead to higher demand and an increase in child sex trafficking as men look to purchase sex from younger and younger girls.

“There are some people in the trade who say, ‘Well, you, know, this is what I choose,’ and I don’t doubt that, but the vast majority of women who have to sell their bodies, I don’t think they are doing it voluntarily,” said O’Neal, who also represents The Episcopal Church at the United Nations as a member of the NGO Committee to Stop Trafficking in Persons. “We should be able to find ways to help them to make a different kind of living and not have to subject their bodies to this.”

During the panel discussion at Incarnation, Iryna Makaruk, a sex trafficking survivor challenged the theory that sex work is work.

“It’s not work; you’re not selling yourself, you’re sold,” she said.

“There are girls being sold all over in run-down apartments, and they are being raped like I was,” said Makaruk, who was 19 and living in Brooklyn when a trafficker lured her in. “Shame on us if that’s how are girls are making money.”

– Lynette Wilson is a reporter and managing editor of Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu