Episcopalians try to counter ‘startling’ problem of food insecurity among college studentsPosted Feb 19, 2019 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] Episcopalians in college towns all over the United States are recognizing that many students have to choose between tuition and books or food, and they are trying to help.

Their ministries, often done in partnership with the schools and local food banks, range from startup to long-established. Many are growing to serve an increasing need. Some are exploring whether what they do is helping. The problem they address is growing and changing.

Food insecurity among college students is often hidden, bolstered by the myth that students who get financial aid have enough money to cover all living expenses. Let Steph Johnson explain it from her vantage point at Grace Café, a part of Christ Episcopal Church, which is across the street from Valdosta State University in Valdosta, Georgia.

A sign on the wall at Grace Café says, “It’s not cheap … it’s free.” About 100 students fill the building on the Christ Episcopal Church campus and spill out onto the deck and another building for the Thursday meal. The cafe is open 8 a.m. to midnight for coffee, snacks and companionship. Photo courtesy of Steph Johnson

“I didn’t realize until I got into this ministry how there are kids who, in order to go to college and get their books, they don’t have any food,” said Johnson.

Food insecurity can be an ongoing issue for some students but only episodic for others, said the Rev. Doug Hale, who runs the Diocese of Oregon’s Episcopal Campus Ministry. Some students come every week, term after term, to the ministry’s Student Food Pantry, located in Eugene one block from the University of Oregon campus. Other students come and go as financial crises hit them or their families. There are also the inexperienced young people who sometimes make bad choices within campus food service systems and the accompanying meal plans, which “assume people make good choices,” he said.

Plus, “there’s always that stigma” and sense of shame that hungry students impose on themselves, said the Rev. Kathleen Crowe, a Diocese of El Camino Real deacon at Canterbury Bridge Episcopal Campus Ministry at San Jose State University in San Jose, California. Bringing the need out into the open helps, she said. When Second Harvest Food Bank’s Just in Time mobile food pantry attracted between 500 to 600 people on the San Jose campus, students saw they weren’t the only ones in need, Crowe said.

Schools with more commuter students find they have different types of hunger issues than schools with a more residential student body, according to the Rev. Eileen O’Brien, who until recently was part of Houston Canterbury, an Episcopal Church ministry serving students in the Texas city. Of the University of Houston’s 47,000 students, she said, only 8,000 live in student housing. Many undergrads are coming from nearby communities and may work and go to school full time. Some have families with “mixed documentation,” which raises issues about who can legally work, O’Brien said.

O’Brien and the Rev. Kevin Johnson, rector of St. Alban’s Episcopal Church in Arlington, Texas, both said international students have different needs and face different financial restrictions. At the University of Houston, international students often get no financial aid, and many of their families back home are making big sacrifices for them to be in school. Often, money from home goes toward tuition, not food, housing or clothing. In addition, F-1 student visas carry stringent restrictions on work, making it harder to make ends meet. A number of international students O’Brien knows work “under-the-radar” jobs, such as lawn care or car parking.

Up at the University of Texas-Arlington where the international student population is mainly Hindu and Muslim, Johnson said, St. Alban’s budding ministry soon realized that it had to tailor its pantry offerings to the students it hoped to reach. The organizers researched foods and spices that are more specific to their diets, according to Doug Hunt, a vestry member. “We learned there’s different types of Hindu diets,” he said, adding that the international student organization advised the group on those choices.

The causes of hunger on campus are many

The Wisconsin Hope Lab said in 2015 that its survey of more than 4,000 undergraduates at 10 community colleges across the nation found that a “startling” 20 percent of students were hungry and 13 percent were homeless. In April 2018, the group said that, out of the 43,000 students it studied at 66 institutions in 20 states and the District of Columbia, 36 percent were food insecure in the 30 days preceding the survey.

The group, now known as the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, defines food insecurity as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or the ability to acquire such foods in a socially acceptable manner,” adding that “the most extreme form is often accompanied with physiological sensations of hunger.”

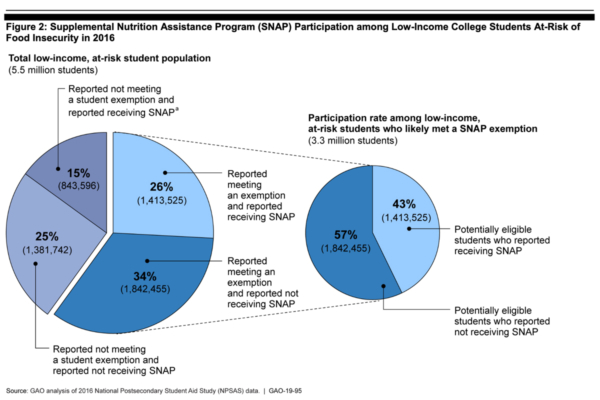

While some students can get federal help via the Food and Nutrition Service’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, not all of them know that. The government’s General Accounting Office, or GAO, told Congress in December that many college students may not have enough to eat, but it found that of the 3.3 million students who were potentially eligible in 2016 for SNAP, commonly known as food stamps, less than half say they participated.

They may have trouble accessing information about their eligibility. The GAO recommends that the Food and Nutrition Service improve student eligibility information on its website and share information on state SNAP agencies’ approaches to help eligible students.

While some may think that hunger is a low-income problem, many students from both lower- and middle-income families who get financial aid struggle to pay for tuition, room and board, books, fees and other costs. Some who do not qualify for aid also struggle.

While some may think that hunger is a low-income problem, many students from both lower- and middle-income families who get financial aid struggle to pay for tuition, room and board, books, fees and other costs. Some who do not qualify for aid also struggle.

All the while, college costs continue to rise. Between 2005-06 and 2015-16, prices for undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board at public institutions rose 34 percent, and prices at private nonprofit institutions rose 26 percent, after adjustment for inflation, the National Center for Education Statistics said last year.

Episcopalians involved in food insecurity work also look for ways to focus attention on the systemic issues that cause it, often by partnering with college administrations. Crowe was invited to serve on a San Jose State committee to address hunger on campus. Hale is also involved with the University of Oregon’s efforts.

It isn’t always easy, though, to get beyond the day-to-day needs. At the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, Rusty Graham, administrator of the Lutheran and Episcopal campus ministry known as Tyson House, which runs Smokey’s Pantry, said, “We’re very limited with the human power that we have that goes into the pantry.” Other groups on campus are trying to address the systemic issues, “but from our perspective, we have to limit our scope to solving the immediate problem.”

Caitlynne Fox, Tyson House ministry coordinator and pantry intern, agreed. “As a campus community, that discussion about addressing the systemic issues has really just begun,” she said.

In her work in Houston, O’Brien tried to convey this reality to Episcopalians and others who are in the position to make systemic changes. She took “the story of real, lived experiences of students on campus and told that story in other places where you had people who could do something about those problems. Campus ministry can help the church [in] building up its consciousness about the lives of young adults,” O’Brien said.

Read more about it

Click here for descriptions of six campus food ministries that Episcopalians are running.

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is the Episcopal News Service’s senior editor and reporter.

Social Menu