Alabama church removes pew, plaque dedicated to Confederate President Jefferson DavisPosted Feb 8, 2019 |

|

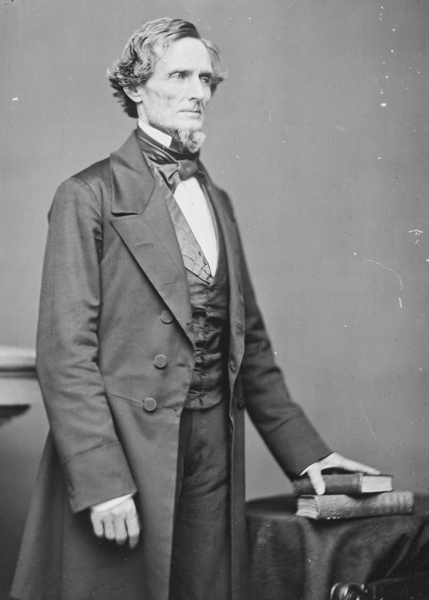

A pew known as the Jefferson Davis pew is seen among newer pews at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo: David Berenguer

[Episcopal News Service] The pew had been an unmistakable fixture for decades at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Online photos show the pew – a cross-shaped poppyhead carved in its wooden finial – sticking out among the rows and rows of newer, plainer-looking pews that filled the rest of the church.

One other detail made this pew stand out: It was known as the Jefferson Davis pew and had an accompanying plaque touting its history, a tribute to the Confederate president who attended St. John’s for three months in 1861 before the capital of the Confederacy was moved from Montgomery to Richmond, Virginia.

Today, that pew is in storage. The congregation removed it recently and moved a newer pew from the back of the church to take its place. The plaque was removed, too. “To continue to allow the pew to be in our worship space would be troublesome,” the Rev. Robert Wisnewski, rector at St. John’s, said this week in a message to the congregation.

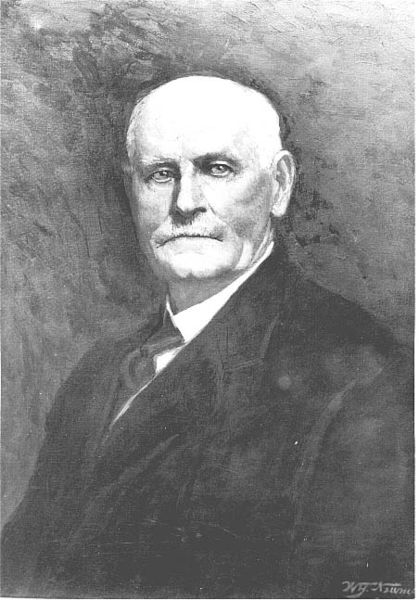

Confederate President Jefferson Davis is seen in this portrait by Matthew Brady. Source: National Archives

At a time when Episcopal churches and institutions across the country are reckoning with their historical ties to slavery, the Confederacy and Jim Crow segregation, Wisnewski and vestry members took steps to set the record straight at St. John’s. They removed the Jefferson Davis pew, Wisnewski said, because its ties to Davis were false and its dedication ceremony 94 years ago was a political act steeped in racism, which runs counter to Christianity.

“Davis was a political figure, not a church figure, nor even a member of the parish,” Wisnewski wrote. “Acting to remove the pew and plaque is the correction of a political act and hopefully will help us all to focus more completely on the love of Christ for all people.”

Wisnewski, when reached by email, declined Episcopal News Service’s request for an interview, saying he had “nothing to add to the statement I’ve made,” though he clarified why the church began scrutinizing the history of the pew and plaque.

“In teaching a Sunday school class this past fall, I became aware of the pew’s dedication not occurring until 1925,” said Wisnewski, who has served at St. John’s since 1995. That detail was the first loose thread that led to the unraveling of the story of the Jefferson Davis pew.

Wisnewski noted the plaque at St. John’s called Davis “a communicant,” but Davis was not yet a confirmed Episcopalian when he attended services at St. John’s. The pew that was dedicated in 1925 wasn’t an original, Wisnewski said. The congregation had replaced the old pews with new ones in the early 1900s. By the 1930s, a pew from Davis’ era had been re-installed and labeled, but its ties to the Confederate figure were uncertain at best.

More troubling was evidence that the 1925 dedication ceremony championed white supremacy as openly as any nods to local history. Its timing, with racism and segregation on the rise, coincided with the “Lost Cause” campaign across the South, which sought to rehabilitate the image of the Confederacy and its leaders by denying the South fought the Civil War to protect slavery.

Montgomery’s roots in antebellum South

In the 1950s, Montgomery would become a pivotal battleground in the civil rights movement, with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, joining others in leading the successful Montgomery bus boycott. But a century earlier, Alabama’s capital city was known as a commerce hub in the slave-powered cotton empire of the antebellum South.

St. John’s Episcopal Church in Montgomery, Alabama, is seen in an undated historic photo. Photo: St. John’s, via website

St. John’s is Montgomery’s oldest Episcopal parish. It formed in 1834, and in 1837, the congregation completed construction of its 48-pew brick church. When membership topped 100, the congregation built a new church in 1855, and slaves were given use of the old brick church, according to a guidebook published by the Civil Heritage Trail.

Montgomery “was the exhilarated, thronging capital of the Confederate States of America” in the first months of 1861, the guidebook says, and Davis was inaugurated the Confederacy’s president in the city on Feb. 18.

Davis was raised a Baptist and only began attending Episcopal services in Montgomery at the urging of his second wife, Varina.

“We have no way of knowing how many times he or his family attended, perhaps only a few times or perhaps as many as a dozen times,” Wisnewski said in his message to the congregation about the Davis pew. “Since Davis was not confirmed, it is probable that he never received Holy Communion here and technically was not a communicant.”

After leaving Montgomery, Davis was confirmed in 1862 at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, once known as the Cathedral of the Confederacy. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee also worshiped at St. Paul’s.

Pew plaques and stained glass windows at St. Paul’s had long touted the Richmond church’s historical ties to those two prominent Confederate figures when, in 2015, St. Paul’s launched its History and Reconciliation Initiative to re-examine that history and consider whether changes were warranted.

A massacre was the catalyst.

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof opened fire at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, killing nine black worshippers. When photos surfaced of Roof posing with a Confederate flag, it fueled a nationwide debate over the racist legacy of such imagery and its embrace by white supremacists.

At St. Paul’s, the congregation decided to remove all representations of Confederate battle flags but to keep family memorials to fallen Confederate soldiers, and the congregation left untouched its plaques marking the pews where Davis and Lee once sat.

In 2017, a violent clash between white supremacists and counterprotesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, over the fate of the city’s Confederate statues led to a new round of national debates and amplified calls to remove such symbols from public display, including at Episcopal institutions. Washington National Cathedral in the nation’s capital removed stained glass windows depicting Lee and a fellow Confederate general, Stonewall Jackson. Sewanee: University of the South in Tennessee moved a statue of another Confederate general from a prominent spot on campus to the university’s cemetery. R.E. Lee Memorial Church in Lexington, Virginia, changed its name back to its original Grace Episcopal Church.

“The argument is simple: The Confederacy fought to maintain slavery and white supremacy in the United States, and this isn’t something the country should honor in any way,” Joe McDaniel Jr., a member of General Convention’s Committee for Racial Justice and Reconciliation, said this week in an interview with ENS.

General Convention has passed numerous resolutions over the years to guide The Episcopal Church as it responds to racism and atones for its own complicity in racial injustice and support for racist systems. Such efforts have led to the creation of the Becoming Beloved Community framework, now the church’s cornerstone initiative on racial reconciliation.

McDaniel, a 58-year-old retired lawyer living in Pensacola, Florida, said he has followed closely the debate over Confederate statues and other memorials in recent years. He disputes arguments that removing such monuments amounts to erasing history. The monuments were not motivated by Southern pride or benign historic preservation, McDaniel said, but rather to promote a cause that was dedicated to keeping black Americans enslaved.

“Most of America is finally coming to terms with that,” McDaniel said. “I applaud St. John’s action in moving the Jefferson Davis pew.”

Little doubt about Davis pew’s racist pedigree

Vestry members made that decision last weekend at a planning retreat, Wisnewski said in his written message, after he brought his research on the pew to their attention, including the evidence that the pew was not in place for the 1925 dedication.

“The lore that the pew had been in place since the beginning of the Civil War and always known as the Jefferson Davis Pew is not true,” Wisnewski said.

The rector also discovered details of the 1925 dedication ceremony, which featured a speech by writer and historian John Trotwood Moore, known as “an apologist for the Old South” who espoused virulent white supremacist rhetoric and defended lynching.

John Trotwood Moore was known as an “apologist for the Old South.” He spoke at the dedication of the Jefferson Davis pew in 1925. Source: Tennessee State Library and Archives

A 1999 article in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly provides a description of Moore’s speech at the dedication of the Jefferson Davis pew, based on contemporary newspaper reports. The event was attended by Alabama’s governor and other civic leaders, and Moore was “their natural choice to deliver appropriate words,” according to the article’s author, Fred Arthur Bailey.

In addition to hailing Davis as a “pure blooded Anglo Saxon,” Moore made a case that racial purity and white superiority were part of Davis’ legacy.

“We are the children not of our father and mother but of our race,” Moore said. “It is well to teach our children that they are well bred, descendants of heroes. Only the pure breed ever reaches the stars.”

Wisnewski indicated that Moore’s role in the dedication of the pew gave little doubt about its racist pedigree.

“Confederate monuments and symbols have increasingly been used by groups that promote white supremacy and are now, to many people of all races, seen to represent insensitivity, hatred, and even evil,” Wisnewski said.

“The mission of our parish is diametrically opposed to what these symbols have come to mean. … Even if the actions which brought about the Jefferson Davis Pew in 1925 were only to memorialize an historical fact, and that appears improbable, the continuance of its presence presents a political statement.”

The vestry voted to remove the pew and place it and the plaque honoring Davis in the church’s archives.

“This was not done to rewrite our history or to dishonor our forebears,” Wisnewski wrote in his message to the congregation. The current vestry would not vote to add such a pew honoring Davis, so it would be “troublesome” to let the existing pew remain.

“St. John’s prides itself in being a spiritual home for all people and a place where politics takes a back seat to the nurture of our souls,” Wisnewski said. “Our worship space is sacred and should direct our hearts to the love of God without distraction.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu