Campus ministers respond to hungry, homeless college studentsPosted Nov 6, 2018 |

|

Kevin Mercy prepares the main course – a potato bar – for the Canterbury USC Late Night Café. The ministry serves 125 to 150 meals weekly. Photo: Glenn Libby

[Episcopal News Service – Los Angeles] The line of hungry students begins to form about 8:30 p.m. each Wednesday at the basement door of the United University Church on the University of Southern California’s Los Angeles campus.

There, volunteer and work-study students who are members of Canterbury USC – the university’s Episcopal campus ministry – have been prepping for hours. They have been chopping onions, baking potatoes, arranging tables and chairs, and placing napkins and condiments on tables for tonight’s potato bar main course, which is expected to help feed an average 120 students who otherwise might go hungry.

If it is a good evening at the Canterbury USC “Late Night Café,” then there will be seconds and possibly even to-go containers, along with beverages and Louisiana crunch cake for dessert, according to Winona, an 18-year-old freshman Canterbury work-study student.

A California native, Winona had no prior religious affiliation but said she was drawn to the Episcopal campus ministry after meeting the Rev. Glenn Libby, the Canterbury USC chaplain, and because of the opportunity to serve other students.

Tuition and fees have spiked as much as 168 percent over the past two decades at private national universities like USC, according to U.S. News and World Report. At public institutions, the increases are even higher, rising more than 200 percent for out-of-state students and 243 percent for in-state students, according to the 2017 report.

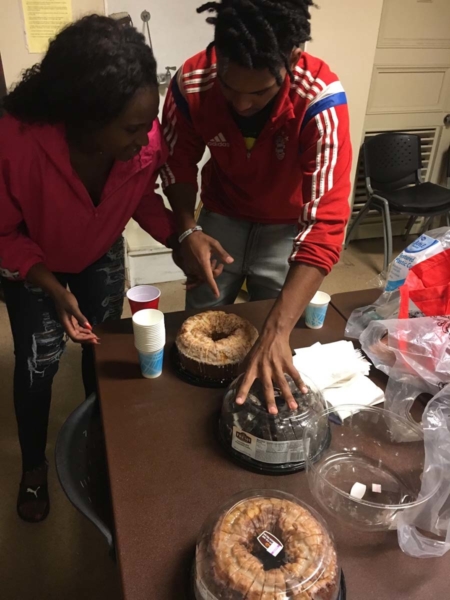

Canterbury USC work-study students Nia (left) and David prepare dessert, Louisiana crunch cake, for students attending the weekly meal. Photo: Glenn Libby

With a $72,000 annual cost for USC tuition, room and board, financial aid dollars – for those who qualify – don’t always stretch, making the meals a necessity for many students, Winona said. All are welcome, and the sense of community and camaraderie has deepened.

“Here, students don’t have to justify why they don’t qualify for financial aid, or if they’re undocumented or in graduate school,” typical reasons why students face food insecurity, Winona said.

On Sept. 4, 2018, National Public Radio reported that the popular image of the residential collegiate experience has vanished.

Instead, of the 17 million undergraduate students in the U.S., about half are financially independent from their parents, one in five is at least 30 years old, one in four is caring for a child, 47 percent attend part time at some point, two out of five attended a two-year community college, and 44 percent have parents who never completed a bachelor’s degree, according to the report.

From New York to California and elsewhere, Libby and other Episcopal campus ministers say they have adapted to the changing needs of such students. Some students are veterans returning from active duty, others are LGBTQ students seeking a safe space. Still others, are “nones” like USC’s Winona, who have no prior religious affiliation and are questioning and soul-searching.

The Rev. Shannon Kelly, the Episcopal Church’s officer for young adult and campus ministry, said the challenge is growing. “It is a nationwide problem that more and more of our campus ministers are becoming aware of and are trying to address.”

The former model of “showing up, having tea, doing Bible study, having worship, whatever that looked like” is in decline, Kelly told Episcopal News Service recently. “Campus ministry varies from place to place, (but) what we’re seeing is a need for food pantries, basic needs pantries, feminine hygiene products.”

Currently, there are about 150 Episcopal campus ministries in colleges and universities nationwide. “Some of those are brand new, and some have been going forever, and they’re all very different,” depending on their locale, Kelly said. Some have even created gardens to offer fresh food for cooking a community meal together.

The Episcopal Church’s Executive Council, through Kelly’s office, this year awarded $139,000 in grants to young adult and campus ministries, according to a May ENS report.

Kelly said student food insecurity relates “to the student debt crisis. The rising costs of school are really impacting how they are able to live outside of school hours.”

If churches are able to help out, it would be a great aid to students, she added. “I was just talking to a chaplain, and they have a lot of veterans on campus. Once a week, the veterans meet and make casseroles for their families. They cook meals for five days to take home. Sometimes, these are the only hot meals their families have all week.”

Homelessness is another challenge in some areas. With a shortage of campus housing, juniors and seniors are often ineligible for dormitory living, “and trying to rent an apartment is more expensive. It becomes this snowball effect,” she said.

Student homeless shelter in San Jose

The Rev. Deacon Kathleen Crowe says she’d love to do Bible study as part of her Canterbury Bridge Episcopal Campus Ministry at San Jose State University in San Jose, California, “but it has not unfolded quite yet, although it may.”

Instead, when she learned some students were sleeping in cars, she started a homeless shelter for them a few blocks from campus, with showers and a food pantry.

At San Jose State, nearly 15 percent of the student population has been homeless at some point during their college education, according to a June 2018 San Jose Mercury News report.

Crowe, a deacon, said she learned that about 300 of the campus’s 35,000 students are homeless, living in cars or couch surfing. “My immediate reaction is, that is just not right and we can’t sit here and do nothing about it and say, ‘Ain’t it awful.’”

She rents space from a local church and converted rooms into dormitory-like spaces. So far, about 20 students have lived there at various times in the past two years. “Eleven are still in residence with me,” she said, but she wishes she could add more.

“The need is very great to support kids who, against all odds, are trying to achieve academic goals,” Crowe told ENS. “Every one of them is a first-generation student with very little financial, emotional, or intellectual encouragement at home.”

She has discovered that evening prayer is “a connection of affection.”

“I’ve found I’ve been most effective by not forcing my theology on these kids,” Crowe said. “And they’ve thanked me for not doing that. And, in that way I’ve been able to express presence, God’s love, which is unconditional.”

She also offers the students “Sacred Suds,” a program to help them launder their clothes, and she passes out buttons with the message #IBIY – I believe in you.

The response from students often is that “they just can’t believe it. It’s like I’m giving them the sacrament – they receive it with such gratitude. We are planting seeds of love,” Crowe said.

She receives financial support from local congregations and a $12,000 yearly diocesan grant, and she contributes part of her own stipend so students may stay in the shelter free of charge. She also helps them find work to become self-sustaining.

“They have to believe you’re authentically caring about them, and when you do, they respond, and then you start to deal with their spiritual needs,” she said.

“If you don’t deal with the basic needs of young people, there’s no hope of getting them to any understanding of who God is, unless we are the hands and feet of Christ … and you do that through unconditional love, not through forcing dogma down their throats.”

The relevance of God

Often, campus ministers are the first line of defense in a growing national mental health crisis, with three out of four college students reporting feeling stressed and having suicidal thoughts, according to a Sept. 6, 2018, ABC News report.

The Rev. Karen Coleman, Episcopal chaplain and campus minister at Boston University, said, “I had a student come in a few weeks ago and say, ‘I need help.’ I walked them over to the health service. Students are bombarded with pressures to perform, study, attend classes, finish assignments, and all the other things going on within yourself in that age group. And, all the questions – Who am I? What am I? It’s a lot to hold.”

The chapel at Boston University offers community meals three times a week for food-insecure students, as well as compline, an ecumenical Eucharist, and a book (not Bible) study, she said.

Most students have no religious affiliation but come “because they like compline. They come because it’s a place for them to rest and be and nobody asks them to explain themselves,” Coleman said. “There’s no paper, there’s no grading, they can just come and be and eat.”

Eventually, the subject of the sacred surfaces.

“It’s both – God and organized religion,” she said. “They are trying to figure out who their God is and not the God of the church they went to before. It’s a safe environment to ask questions, maybe those questions you can’t ask of your parish priest but can ask here because that’s what a university campus is all about, asking those questions.

“A lot of it is just being in the space to allow them to move out of the language that they had when they were in high school and to really take a deep, hard look at how God is working and moving in their lives.”

Student food insecurity is very much in focus at SUNY-Ulster’s 2,000-student campus in Stone Ridge, New York, about 90 miles north of Manhattan, according to the Rev. Robin James.

A Canterbury alum from the University of Kansas, James said the ministry today is very different than the one she remembers. “Students come and ask if they have to be a member of the group or a Christian to participate in the pantry,” James told ENS recently. “Of course, we say no. This is about feeding people with dignity and respect.”

The number of student pantry guests rose from 400 to more than 600 in the past two years, James said, and students are facing such issues as, “Do I pay my tuition or have dinner tonight? Do I buy a $100 textbook that I can’t read online, or pay my electric bill? If I don’t pay my electric bill, I can’t stay connected to the Internet.”

A Sept. 2018 Wisconsin Hope Center survey of 262 participating colleges and universities indicated that 217 currently operate food pantries, yet most are hampered by insufficient funding, food and volunteers.

James, who helps run the Ulster pantry, said there are 37 active food pantries in the State University of New York system. The average age of students in 2015 on the Ulster campus was 33.

She also has counseled students on the brink of homelessness. “It’s the same kind of reasoning. If I’m going to pay $2,500 a semester in tuition, something has to give somewhere,” James said. “We have students working two to three jobs with two or three children and a spouse and trying to complete successfully a course of study.”

She doesn’t do worship but, instead, sits in the food court area with a sign that says “Faith Matters,” and she is thinking of reprising an interfaith Thanksgiving dinner, at the request of a Muslim student.

Traditional ministry models aside, “people remember where they found comfort and solace,” she said. “Food and acceptance – non-judgment – that’s what they’re looking for. And if they weren’t raised in a church, which is increasingly the case, they’re like, ‘Hmm … tell me some more about this God thing.’”

– The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a correspondent for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu