Growing congregation in ‘Rust Belt’ city offers model for two dioceses poised for partnershipPosted Oct 24, 2018 |

|

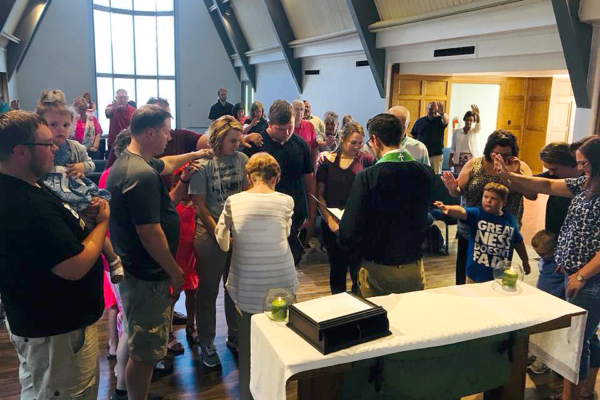

Worshippers bless high school graduates during a service June 3 at Resurrection Church in Hermitage, Pennsylvania. In February, the congregation began worshipping in the renovated sanctuary of a vacant former Episcopal church. Photo: Resurrection Church, via Facebook

Editor’s note: The Episcopal Dioceses of Northwestern Pennsylvania and Western New York voted Oct. 26 to share a bishop and a staff for the next five years as they explore a deeper relationship focused on creating new opportunities for mission.

[Episcopal News Service] The story of the Episcopal Church’s renewed presence in Hermitage, Pennsylvania, might be summed up as “Back to the Future.” Or, in the Rev. Jason Shank’s words, his services at Resurrection Church offer a “fresh expression of vintage Christianity.”

Comfortable seats, no pews. A small, less-imposing altar. Contemporary music. Modern-language prayers. No copies of the Book of Common Prayer because the text is projected onto the wall. “We’re not your traditional Episcopal church,” Shank said.

Resurrection Church is a new congregation – a church plant – but while it’s not your traditional church, it’s not your traditional church plant either. Rather than upending old models in the search for new communities of faith, the congregation still worships on Sundays, emphasizes prayer and sacrament, bases its Eucharist on Rite II and gathers in a building that looks unmistakably like a church.

The mix of contemporary and classic offers a vision for Episcopal congregation redevelopment that could take hold beyond the limits of this small city of about 16,000 in northwestern Pennsylvania on the Ohio state line. The Diocese of Northwestern Pennsylvania is poised to seal a partnership agreement with the Diocese of Western New York that would allow the two dioceses to share resources and enable more experiments like this, as both try to stem congregational decline in a region undergoing demographic and economic changes.

“I think there are places across Northwestern Pennsylvania and Western New York that have real potential for redevelopment and church planting,” said Northwestern Pennsylvania Bishop Sean Rowe, who would add the title of Western New York provisional bishop if the partnership plan is approved this weekend at a joint convention in Niagara Falls, New York.

Rowe noted unique challenges in this “depopulating region,” one sometimes said to be part of the Rust Belt because of its fading manufacturing sector. Hermitage is part of a metropolitan area centered around Youngstown, Ohio, and known for its steel mills. This city east of Youngstown has maintained a relatively stable, but aging, population. Its mostly white residents have a median age of 48, and a quarter are 65 or older, according to census figures. About 8 percent of residents live under the poverty level.

Episcopal church planters typically are encouraged to locate their new congregations in growing communities that don’t already have an Episcopal church, but many of the communities in these two dioceses are stagnant or shrinking, Rowe said. How will the Episcopal Church maintain a robust presence here?

As one case study of success, Resurrection Church has lived up to its name.

Episcopalians in Hermitage had long worshipped at Church of the Redeemer, but the Diocese of Northwestern Pennsylvania closed that church in early 2016 after its effort to combine Redeemer with two other congregations didn’t achieve the rejuvenation the diocese had hoped it would. At the same time, the diocese had spent nearly a decade building a cash reserve to launch its first new congregation in 50 years.

The Rev. Jason Shank is a former Methodist pastor with a background in new congregation development. Photo: Resurrection Church, via Facebook

For that task, Rowe recruited Shank, a former Methodist pastor who recently had been ordained as an Episcopal priest. Shank’s background was in new congregation development, which he studied at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. He worked with three church plants in Maryland after graduation.

Shank, 33, began attending Episcopal services with his wife while she was studying at General Theological Seminary in New York City to become an Episcopal priest. “In the end, I just felt my home was in the Episcopal Church,” Shank said. He was confirmed by Rowe in 2015 as part of his Episcopal ordination process. By then, he and Rowe already were talking about a church plant in the diocese.

“We knew something was going to happen in Hermitage,” Shank said. Large evangelical and Roman Catholic churches dominated the city’s denominational landscape, but Rowe and Shank saw an opportunity to add a new Episcopal voice to the conversation, one that was more progressive and community-minded.

With Rowe’s encouragement, Shank and about a dozen other Episcopalians began gathering in February 2016 to develop a new congregation in Hermitage.

The initial group began worshipping in people’s homes and in parks, as is common for church startups, before arranging to worship regularly at an ambulance service’s headquarters. The space was centrally located and offered a sound system, a projector and other technology Shank needed to lead the services.

But after about a year, the ambulance service ended its agreement with the fledgling congregation, and Shank was back to hunting for locations. “I basically went anywhere I could think of to find a facility to rent, and none of them worked,” he said. Finally, the congregation looked back to the now-vacant Church of the Redeemer building, and “it seemed to be the only option, and maybe the best option,” Shank said.

Resurrection Church, with help from a $100,000 church-planting grant, began renovating the former Church of the Redeemer building in summer 2017. Photo: Resurrection Church, via Facebook

It was important to “make sure people knew this was a new church,” Shank said. He described the former church as geographically and socially isolated from the community, and many Hermitage residents may not even have known it was an active church or noticed when it closed. Shank’s congregation started from scratch, gutting the sanctuary and renovating the space to offer a more welcoming environment. Services moved into the renovated sanctuary in February.

Members of the congregation also spread the word about Resurrection Church in variety of ways. They set up a tent and table along the route of a local parade, offered the church building as a polling place during local elections, hosted a beanbag toss competition on the church lawn and connected with people through social media. Individual invitations to worship are still the most valuable tools for evangelism, Shank said.

With all that activity, the congregation has grown slowly but steadily, and more than 50 people, including Rowe, attended consecration of its new worship space on Sept. 23.

Resurrection Church got an early boost in 2016 from a $100,000 church-planting grant approved by the Episcopal Church’s Executive Council. These grants help cover startup costs and come with a churchwide support network overseen by the Rev. Mike Michie, staff officer for church planting infrastructure.

Michie often speaks of the need to grow new congregations in locations and communities that make the most sense – a growing suburb, for example, rather than a dying downtown. But Resurrection Church is a more nuanced example. Cities and neighborhoods change over time, and “now some of our churches are back in the right place again,” Michie said.

The diocese made the difficult decision to close the struggling Church of the Redeemer, Michie said, and allowed time to push reset, getting a new leader, new name and new approach to ministry that would allow a congregational “resurrection” to happen in Hermitage.

“I think we need to watch and pray for this church, because what that diocese is doing and what Resurrection is doing could be a very effective model for many different places in the Episcopal Church,” Michie said.

The congregation’s “fresh expression” of what it means to be Episcopalian in Hermitage is driving its growth, but Shank is pragmatic about the decision to go back to the old church building.

“New isn’t always trusted in this area,” he said. “There’s almost like this narrative in Hermitage of ‘good things don’t happen.’ … We get to rewrite the narrative. We get to tell the narrative that the new thing we’re doing is going to be good for the community because we care about the community.”

Northwestern Pennsylvania Bishop Sean Rowe joins Resurrection Church on Sept. 23 for its consecration service. Photo: Resurrection Church, via Facebook

The same could apply to other Episcopal congregations and communities in the diocese, Rowe said.

“In this region, people are not over Sunday morning. Sunday morning is still the time people worship. Many people still expect it to look like a church,” Rowe said. “And unless the Episcopal Church is to become only an urban-suburban phenomenon, then we need to crack the code of places like the Rust Belt.”

Western New York Bishop William Franklin said he has been encouraged by the story of Resurrection Church as a model for what might be possible across both dioceses.

“I believe that, here in Western New York, there are many opportunities for similar kinds of church development and redevelopment,” Franklin said in an emailed statement. “In a region like ours, which is undergoing economic and cultural revival in many forms, many communities are eager for new ways to build flourishing churches and experience God’s grace in new ways.”

The two dioceses already have been sharing certain operations for the past five years, and they began discussing a more formal collaboration after Franklin announced in April 2017 he would be retiring. More than 500 people attended eight subsequent listening sessions on the proposal, which diocesan leaders stressed is not a merger, and in May 2018, both standing committees voted unanimously to support the plan.

At the joint convention Oct. 26-27, Western New York will vote on whether to make Rowe its bishop provisional for five years. By formalizing this collaboration, the goal isn’t just to cut costs and survive, Rowe said. Rather, he hopes to leverage the scale of a combined 90 congregations to try new ministries and ways of being church in this corner of the world.

Some of those experiments might look a lot like Resurrection Church, but Rowe is leaving the door open to all possibilities.

“I’m trying to not predict or put out all of the ideas of things that can happen,” he said, “I just don’t think we know. I think it’s going to take working together and engaging in intentional processes, and [we’ll] see what emerges.”

Shank agrees that the future of the two dioceses is wide open, but he thinks his congregation may have valuable lessons to offer other church leaders in his diocese and the diocese to the north.

“Something like church planting and growing congregations is a need no matter what,” he said. “The same things that are done in church plants can help traditional congregations or stand-alone congregations or mission congregations to grow. … If we can do it here, what will that translate to or look like in Western New York?”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu