Episcopalians confront hard truths about Episcopal Church’s role in slavery, black historyThe goal: ‘Becoming Beloved Community’ now and in the future.Posted Feb 26, 2018 |

|

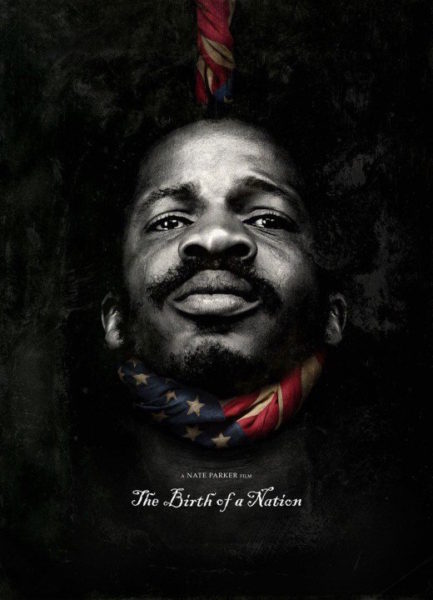

Vivian Evans, center, shares her thoughts after “The Birth of a Nation” film screening at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan Feb. 22. The Diocese of New York designated 2018 as “The Year of Lamentation” for its role in slavery — one Episcopal effort among many across the United States. Photo: Amy Sowder/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] Brutal scenes of physical and psychological violence in the 2016 film “The Birth of a Nation” flashed across a screen set up inside a small chamber at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine. A few viewers turned away, while some gasped and others watched steadily.

The film is based on the true story of Nat Turner, a slave preacher who led a rebellion in 1831.

Vivian Evans, 82, didn’t turn away.

“When I was 10 years old, I interviewed friends of my grandmother’s in Mississippi who had been slaves. She had me pick cotton to see what it was like, and I pricked my fingers just like they did in the movie,” Evans, a member of Trinity St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in New Rochelle, New York, told the others during a discussion after the film.

“The Birth of a Nation” is a 2016 film inspired by the true story of Nat Turner, a lay preacher slave who led a rebellion in 1831. Photo: Fox Searchlight Pictures

The Episcopal Diocese of New York Reparations Committee on Slavery organized the film screening and discussion as part of its Year of Lamentation to examine the diocese’s role in slavery. It’s one of a growing number of events across the United States as the Episcopal Church seeks racial reconciliation and healing among its congregations and wider communities.

“Lamentation is actually an opportunity; it’s beginning to open our eyes to what actions are possible for us. We can’t do that until we’ve owned our beginnings more fully,” said the Rev. Richard Witt, executive director of the statewide nonprofit Rural & Migrant Ministry and member of the Episcopal diocese’s reparations committee.

Black history in the Episcopal Church

Although much has been done at more recent General Conventions and throughout the church, this New York committee was created 12 years ago in response to three 2006 General Convention resolutions. One resolution asked the church to study its complicity and economic benefits from the slave trade. A second resolution said to “engage the people of the Episcopal Church in storytelling about historical and present-day privilege and under-privilege as well as discernment towards restorative justice and the call to fully live into our baptismal covenant.” The last resolution called for the church to support legislation for reparations for slavery.

In 2014, the New York diocese created a three-part video that examines slavery; it can be viewed on YouTube. The committee has since established a prayer blog and is asking priests to integrate these messages into their sermons. The Year of Lamentation includes a schedule of community events, from book and film discussions to walking tours, pilgrimages and forums. Organizers said they are especially proud of the theatrical presentation, “New York Lamentation,” featuring figures in the history of the diocese, from clergy to slaves and lay people, revealing how a number of churches were built by slaves. The show premiered in Staten Island Jan. 21, and continues in Poughkeepsie March 4, in Manhattan Sept. 23, and in White Plains Oct. 14.

“This is not about trying to lay guilt on people. It’s about what we’ve done institutionally and systemically. The notion of white supremacy is woven into the fabric of this country,” historian Cynthia Copeland told Episcopal News Service. She’s co-chairwoman of the reparations committee and member of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery in Manhattan. “If you take time to remove yourself personally and detach, it may be a little bit more palatable to take off those defenses and listen, instead of hanging onto those myths established in our society.”

“We’re asking people to think more critically of where we’re heading,” Copeland said. “This is not a one-time, check-it-off-your-list thing. It is about really internalizing this and making a lifelong work of questioning, having discussions, listening.”

Church practices have treated African Americans as “other,” dependents in need of charity similar to those in mission fields abroad, rather than as equal citizens, according to a timeline on St. Mark’s website that identifies some of events in African Americans’ struggle for recognition in the Episcopal Church.

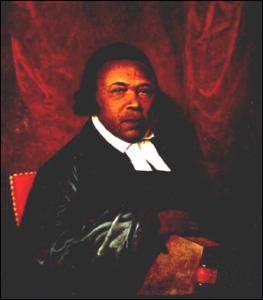

February is Black History Month, an annual celebration of achievements by African Americans and a time for recognizing the central role of blacks in U.S. history. On Feb. 13, Episcopalians often commemorate the Rev. Absalom Jones, the first African American priest ordained in the Episcopal Church. While that history includes notable achievements, it’s mired in oppression and inhumane treatment, which are also woven throughout Episcopal history — whether or not churchgoers talk about it, Copeland said.

But Episcopalians must talk about the horrors of the past and the inequalities of today, as well as do something to change the present and future — not just in February, or this year, but indefinitely, said the Rev. Stephanie Spellers, canon to the presiding bishop on evangelism, reconciliation and creation care.

Becoming Beloved Community is a four-part vision

To help dioceses and congregations take on this lifelong mission, in the spring of 2017, the Episcopal Church released its “Becoming Beloved Community” vision for racial reconciliation efforts. General Convention in 2015 allotted $2 million to this work.

The release followed a year of listening, consulting and reflection by Presiding Bishop Michael Curry, House of Deputies President the Rev. Gay Clark Jennings and the other officers of the House of Bishops and House of Deputies. They invited Episcopalians to study and commit to this mission.

The vision is four-fold, and more like a lifelong labyrinth rather than a chronological to-do list. The first part, however, must be done before the others are possible, Spellers and other racial healing activists say.

Telling the truth: Who are we? What things have we done and left undone regarding racial justice and healing? Churchwide initiatives include a census of the church and an audit of racial justice in Episcopal structures and systems.

Proclaiming the dream: How can we publicly acknowledge things done and left undone? What does Beloved Community look like in this place? What behaviors and commitments will foster reconciliation, justice and healing? Initiatives include holding regional, public sacred listening and learning engagements, launching a story-sharing campaign and allocating the budget for lifelong formation of transformation.

Repairing the breach: What institutions and systems are broken? How will we participate in repair, restoration and healing of people, institutions and systems? Initiatives focus on justice reform, re-entry collaboratives with formerly incarcerated people returning to community and partnership with Episcopal historically black colleges and universities.

Practicing the way: How will we grow as reconcilers, healers and justice-bearers? How will we actively grow relationship across dividing walls and seek Christ in the other? This also involves the Becoming Beloved Community story-sharing campaign, as well as reconciliation and justice pilgrimages; multilingual formation and training; and liturgical resources for healing, reconciliation and justice.

In the past year, leaders nationwide have made a great start, Spellers said.

“What the presiding bishop and the officers hoped for was to offer up a framework, not necessarily a program, for racial reconciliation,” Spellers told Episcopal News Service. “Do your discernment. What does it look like to tell the truth about your church, who we are and who we have not welcomed over the year? Do your discernment over what it looks like to practice love, to be reconcilers and healers, what you need to do to repair the breach.”

The Episcopal Diocese of Iowa hosted a community conversation to address racial equity gaps in education in the Iowa City school district on Jan. 22. Photo: Meg Wagner/Diocese of Iowa

What other churches and dioceses are doing

“While I’m proud of what they’re doing here in New York, this diocese is by no means the first to grab this and run,” Spellers said.

Washington National Cathedral was one of the first to sign on, doing conversations on the church’s legacy of slavery, including their windows, which depicted the Confederate flag and Civil War. Cathedral leaders continue to host public programs, which are live-streamed for the rest of the Episcopal Church to participate. The Episcopal Church is a co-sponsor of this, which is a strong example of the second part of the labyrinth, Spellers said.

Based in Seattle, Washington, Heidi Kim, staff officer for racial reconciliation for the Episcopal Church, recently talked with Episcopalians in Massachusetts, where they’re doing an audit of the ordination process, studying the people who’ve dropped out, and looking at patterns of exclusion that people of color, women and LGBTQ might be experiencing.

Kim has visited Southern dioceses with historically black and historically white parishes in small towns where they can no longer afford to operate as separate congregations and need to merge.

Often, separate parishes exist because the black church members weren’t allowed to go to the white church. The black churches are smaller and in need of more repairs compared to the white churches, she said. They need to engage in story-sharing and discuss what to celebrate and what they will lose when they merge, she said.

“This is not just about getting stuck in the guilt, but remembering those difficult dark moments of the past, not to shame and blame people, but so that we don’t make those same mistakes again,” Kim told Episcopal News Service. “This is part of our baptismal covenant, to repent and turn to a new way. People of good will and intentions allowed some pretty terrible things to happen. And it’s easy to do if we’re not intentional and creating beloved spaces for everyone.”

The Episcopal Church has partnered with the Diocese of Atlanta’s Beloved Community Commission on Dismantling Racism, putting $50,000 into the efforts, said author and activist Catherine Meeks, the commission’s chairwoman.

Meeks is also founding executive director of the Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing, which opened in October in Atlanta for the benefit of not just Georgia, but the wider church.

As part of this effort, the diocese organized a Province IV conversation, which drew representatives of 20 dioceses, as a pilot for a wider conversation scheduled for Feb. 28-March 1, drawing representatives from at least 28 dioceses, from Minnesota to Missouri. It’s for Episcopalians involved in racial healing work to share what they’re doing and how they want the center to be involved in what they do going forward. Meeks is trying to create a better communications system so that people don’t feel alone in their work.

But this work isn’t just for church leaders, Meeks emphasizes. Nor is it only for churches with diverse congregations.

“People in predominately white congregations think there is nothing they can do because there aren’t any other kinds of people there, but connect with someone you don’t normally talk to. Try to build a bridge with anyone you see as ‘other’ in any way, like politically or economically,” Meeks told Episcopal News Service.

“Racism is one kind of oppression, but there are many other kinds of oppression we live by. Any time you make an effort to be more open and caring and courageous, that will spill out into all the rest of your life. There is always some ‘other,’ alien-ness.”

People have to find what resonates with them, she said, encouraging Episcopalians to start book studies or something as simple as inviting someone unfamiliar out for coffee. “You do have to do something. You don’t get to just sit around and think about it for the rest of your life,” Meeks said.

Letting a person of color, or anyone who feels oppressed, share her or his experience, without interrupting, judging, correcting or editing it, is key, Meeks said.

Churchwide organizations, provinces and dioceses are joining the effort

Reforming the criminal justice system and helping previously incarcerated people re-enter the community were the focus of a fall conference organized by Province VIII, which includes Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Navajoland, California, Idaho and the Pacific Northwest.

The United Thank Offering ministry identified Becoming Beloved Community as its 2018 grant theme, asking grant applicants to show how they would put the vision into action. “That’s going to spark all kinds of engagement, because once you have the money, you can take your idea and execute it,” Spellers said.

Bishops from the Diocese of Indianapolis, Diocese of Northern Indiana and the Lutheran Indiana-Kentucky Synod meet regularly to plan how to engage in the Becoming Beloved Community vision, releasing a video to encourage story-sharing.

Telling the truth, proclaiming the dream, repairing the breach and practicing the way are the four parts of the Episcopal Church’s Becoming Beloved Community vision, which the Diocese of Iowa is interpreting locally to meet community needs. On Feb. 10, there was a church leader training. Photo: Meg Wagner/Diocese of Iowa

The Diocese of Iowa is creating a new Racial Justice Center in the heart of Iowa City, using the church’s Becoming Beloved Community guide as its framework. “Those people are on fire. They’re amazing,” said Spellers, who was the keynote speaker for the annual diocesan conference in October. “They want the rest of the heartland to follow.”

The diocese received a Mission Enterprise Zone grant of $75,000 for the center and its work.

The area has struggled with its changing demographics, said the Rev. Meg Wagner, the diocese’s missioner for communication and reconciliation. “We’ve heard things like ‘I don’t see color,’ ‘we don’t have a race problem because we’re mostly white,’ or ‘because we’re surrounded by mostly white people, we don’t know how to talk about race and deal with our white guilt,’” she said. “There’s a recognized need for more understanding of our history of race and oppression.”

There will be community discussions on equity gaps in education; pilgrimages following the underground railroad; an urban retreat with meditation; Freedom School curriculum, founded during the 1960s Civil Rights era to empower black Americans; a summit for women and girls of color; and a summer tour to prepare young black students for college.

“We want this to be about empowering people to be nonviolent agents for change in the world,” Wagner said.

This churchwide effort is by no means a straight, clear path, leaders say. That’s why Becoming Beloved Community is a labyrinth, Wagner said.

“You just have to keep walking this path; it’s going to last a lifetime,” she said. “And just like a labyrinth, you’re never finished. But standing still is not an option for us anymore, as far as we’re concerned.”

— Amy Sowder is a special correspondent for the Episcopal News Service and a freelance writer and editor based in Brooklyn. She can be reached at amysowderepiscopalnews@gmail.com.

Social Menu