Episcopal churches help communities grapple with the opioid crisisPosted Oct 11, 2017 |

|

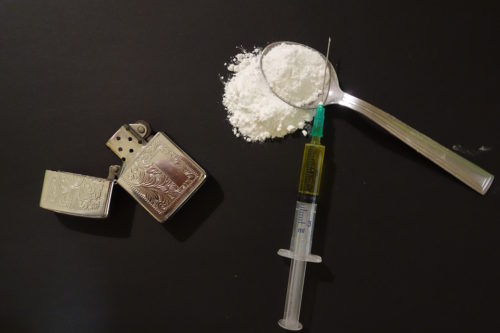

People who are addicted to opioids take them in pill form by mouth, in a powder by nose and in a liquid injection, usually in the arm. Photo: Pixabay

[Episcopal News Service] If someone with diabetes starts shaking and seizing with insulin shock, would you try to help? What about if someone was grimacing in pain from a heart attack right before your eyes — would you call 911?

Of course, you would, said Donna Barten, 56, a recently retired research neuroscientist on the outreach committee of Christ Church Cathedral in Springfield in the Episcopal Diocese of Western Massachusetts.

That’s why Barten organized a Narcan training event at her church in September. Narcan is the brand name for a nasal-spray variety of naloxone, which revives people after they’ve stopped breathing from an opioid overdose. It’s simple and safe to administer, she said. One of Barten’s goals is to enable most of the churches in her diocese, as well as the area’s synagogues and mosques, to have Narcan and know how to use it.

“I’d like us to be a safe place where people can go for help,” Barten said. “Where is the hand of Jesus these days? They’re treated like lepers. This is one way that we can help.”

Donna Barten organized a Narcan training workshop attended by 16 clergy and laypeople from Christ Church Cathedral, neighboring South Congregational Church, Our Loaves & Fishes feeding program, and the entire office of Open Door Social Services. In part of the training, Barten used this video from the makers of Narcan that demonstrates how simple it is to use. Narcan’s marketers advise to use their product first, but Barten recommends calling 911 first to get trained medical professionals to the overdosing person as quickly as possible. Photo: The Rev. Tom Callard, dean of Christ Church Cathedral

Through workshops, plays, awareness campaigns, meetings and training sessions, Episcopalians across the United States and Anglicans in Canada are reaching out in their communities to educate people about the epidemic of opioid addiction. They’re teaching how to spot the symptoms of overdose, and they’re trying to give church members the tools to be of service in an emergency.

Narcan is one way to save a life. But critics say Narcan enables addicts to continue using.

Several Episcopalian leaders respond: Addicts can’t recover if they’re dead. “We, as non-addicts, cannot even begin to comprehend. We’re giving them a chance to recover. They don’t really want to be addicts. It’s a miserable life,” Barten said.

Helping the sick

Most people wouldn’t refrain from providing whatever emergency help they could, even if the suffering person’s disease, such as diabetes or heart disease, was self-inflicted by unhealthy eating habits and lack of exercise — and even if that person will continue those lifestyle choices after being revived, Barten and other Episcopalians say.

Addiction — often referred to as substance use disorder in the medical world — is a disease too. It’s listed as such by the American Medical Association and many other reputable organizations. Like some types of diabetes, cancer and heart disease, addiction can be caused by a combination of biological, behavioral and environmental factors. The American Psychiatric Association calls addiction a complex condition, a brain disease that is manifested by compulsive substance use despite harmful consequence.

“When I read more about addiction, read about how the brain changes after drugs, and how the brain was already different in the first place, I see it completely as an illness,” Barten said.

That’s the thinking behind helping people dying from an overdose, even if it’s not their first. The use of naloxone kits by laypeople reversed at least 26,463 overdoses in the United States between 1996 and June 2014, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Providing opioid overdose training and naloxone kits to laypersons who might witness an opioid overdose can help reduce opioid overdose mortality,” the centers concluded in a 2015 report.

In Springfield, there were 882 opioid-related emergency medical service incidents in 2016, up from 702 such incidents in 2015. Forty-one people died from overdose each of those years, according to the Springfield Coalition for Opioid Overdose Prevention, coordinated by the City of Springfield’s Department of Health and Human Services.

Frances Stewart, 70, had struggled with heroin use for at least 15 years. Then in Sept. 2016, she overdosed after sniffing two bags of heroin at a friend’s house and went out cold. Her friends called 911, and paramedics brought her back to life with Narcan.

Frances Stewart, 70, was saved by Narcan when she had a heroin overdose in 2016. She’s been in recovery ever since, working to spread awareness and hope at Christ Church Cathedral in Springfield, Massachusetts, and through the Voices from Inside writing program for inmates. Photo: Donna Barten, Christ Church Cathedral

“They asked my age and when I told them, they were surprised because people on heroin usually don’t live that long. That’s when it really hit me, and I’ve been clean ever since,” Stewart said. She told her story at Barten’s Narcan training workshop, and she attends services at the Springfield cathedral sometimes. “I was so scared, I quit after that OD. I truly believe it saved my life.”

While imprisoned at Chicopee Women’s Correctional Center on heroin charges, Stewart took a Voices from Inside writing class co-facilitated by Barten. Now out, Stewart is training to be a writing facilitator herself and help others still in jail. She earned a college degree decades ago, before drug addiction took hold of her life. Now, she’s a grandma who can be present for her grandchildren, she said.

How the opioid crisis has evolved

Prescription opioid pills were the drugs of choice for addicts in the last decade or so, but that’s changed.

The crackdown on pill mills, especially in Florida, one of the top states suffering from this particular addiction, meant it was harder to get a prescription and more expensive to buy opioid pills on the street. Even in states where there hasn’t been much of a crackdown, users turn to heroin because of the price. Heroin can cost only $4 a bag, Barten said.

But the crisis is intensifying because heroin is being cut with fentanyl, which is about 10 times stronger. This adulteration oftentimes happens without the user’s knowledge. Worse still, an elephant tranquilizer called carfentanyl is now going around, and it’s 10,000 times more potent than morphine.

Users just released from rehab or jail can die from their first sniff or injection of an opioid if they relapse. And relapse is common, especially without proper support.

Opioids are a class of drugs that include illegal heroin, as well as synthetic painkillers such as Vicodin, Percocet, codeine, morphine, and OxyContin, among many others. They block pain and are safe when prescribed by a doctor for a short time, but the medicine also produces a dreamy euphoria that can lead to addiction when a patient becomes dependent on them and then misuses them. That’s when opioid pain relievers can lead to overdoses and deaths.

OxyContin was supposed to be a safer, time-released pill when it was released in 1996, but people learned they could break it down into a powder to inject or snort and get a more extreme high all at once. Drug overdose deaths nearly tripled between 1999 and 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control, and six out of 10 of those deaths are due to opioids.

People addicted to opioids sometimes crush the pills into a powder to either snort up the nose or to liquefy for injection. Photo: Pixabay

The agency reports that 91 opioid deaths happen every day in the United States, including from prescription opioids and heroin. Three out of four new heroin users started by abusing opioids.

West Virginia is considered the heroin capital of the United States, with an overdose death rate of 41.5 out of every 100,000 people. It’s a fact reiterated by anyone from the Rt. Rev. W. Michie Klusmeyer, bishop of Diocese of West Virginia, to Jan Rader, deputy chief of the Huntington Fire Department in West Virginia in the 2017 “Heroin(e)” Netflix documentary.

Huntington is in the rural western portion of the state, dominated by coal mining, financial hardship, lack of education and poverty. When physical laborers get injured and are prescribed opiates for their legitimate need, the craving can kick in. “It’s kind of like a recipe for disaster,” Rader said in the film.

Interstates 70 and 80, which connect West Virginia to Baltimore and Washington, D.C., are known as heroin highways, said Klusmeyer, who’s also the Episcopal Church’s Province 3 president.

At a provincial synod meeting in 2015 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, near I-70, attendees faced the fact that nearby Jefferson County, with a population of 53,500, had more opioid overdose hospitalizations than the entire city of Baltimore, Maryland, population 621,900, he said. “Not percentage wise, but numbers-wise,” Klusmeyer said.

“So, we said we’d try to work together to see what we could do.”

What churches are doing

Training and equipping people to use the overdose drug is one powerful way to help, although a short-term fix.

Recovery Ministries of the Episcopal Church is an independent, nationwide network of clergy, laypeople, agencies and institutions offering resources on how to handle the effects of addiction. Although inclusive of all addictions, the network’s original mission stems from the landmark 1979 General Convention resolution on alcohol.

In the Canadian Anglican Diocese of Ottawa, the Rev. Monique Stone, rector of the three-point Parish of Huntley, organized a naloxone workshop at St. Thomas the Apostle Anglican Church in Ottawa in February for 20 clergy, including diocesan Bishop John Chapman.

St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Eggertsville, in Buffalo, New York, hosted a free Narcan/naloxone training in April. Offered by the Erie County Department of Health, the session leader was a registered nurse.

Massachusetts’ Health and Human Services Department in Springfield trained Barten to teach others how to use Narcan. At the inaugural Narcan workshop in September, she invited the church’s clergy, diocesan staff, soup kitchen staff, and people from the neighboring church who run a soup kitchen on alternate days.

The Springfield cathedral is downtown near low-income housing with a reputation for drug dealing. The cathedral’s community garden is open to the public, and so is the bathroom and soup kitchen. They’ve seen people using drugs in front of their church.

“Opioid addiction is an issue right in our neighborhood, so to have Narcan would make sense,” Barten said. “We want to have more training sessions and have a booth at the diocesan convention. Stigma is one of the major issues with this.”

Barten has been creating educational materials, and she’s writing a three-part article series for her diocesan newsletter.

Many state laws restrict Narcan from over-the-counter use. The Federal Drug Administration has also approved two forms of injectable naloxone, one that requires professional training and the other an auto-injectable version that comes in a device that, once activated, verbally gives instructions on its use.

Lauren Wilkes-Stubblefield, an Episcopalian and communications consultant, isn’t allowed to use Narcan, even though she’s a firefighter and emergency medical responder for Hinds County, Mississippi. “I cannot even administer it in the field with my level of training,” she said.

Church leaders are finding creative ways to spread awareness of the problem.

The Rev. Ron Tibbetts, deacon at Trinity Episcopal Church in downtown Wrentham, Massachusetts, led a campaign to post signs with the number 2,069 across the town and area communities. That’s number of townspeople who died from opioids in 2016.

The theater ministry of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Jamestown, New York, created a play to help to fight the prevalence of opioid addition and overdose deaths in Western New York. “Least Resistance” is an original script that compiles stories of people affected by drug use. The show was directed by Steven M. Cobb, himself in long-term recovery.

The Diocese of West Virginia, independently and through the West Virginia Council of Churches, is leading the state in the fight, Klusmeyer said. On May 2, the diocese held both a Clergy Day devoted solely to addiction and a statewide clergy gathering, with more than 350 clergy of all denominations in attendance. “For the first time in history that we know, clergy of all stripes came together from the state,” Klusmeyer said.

About 350 clergy of many denominations from throughout West Virginia gathered May 25 at West Virginia Wesleyan College in Buckhannon to discuss the opioid overdose crisis, the impediments and possible solutions. Photo: Episcopal Diocese of West Virginia

Twelve “listening events” were held around West Virginia, which revealed some of the roadblocks to solving the crisis. A big issue is that state agencies offer Narcan training, but at the moment, churches are not permitted to dispense them.

The West Virginia Council of Churches thinks there should be some simple fix. “I dare the legislature not to change it, in light of the realities in West Virginia and around the country,” Klusmeyer said. “Our legislature meets in January and February, and we will present this legislation to allow churches to do this.”

Klusmeyer acknowledges that Narcan isn’t the only solution. But neither is jail.

“We cannot incarcerate this to a healthy solution,” Klusmeyer said. “It’s not about arresting the drugged person and throwing them in jail. It’s about health care and offering all the assistance necessary. How do we make that happen?”

Bishop W. Michie Klusmeyer leads a gathering of multidenominational clergy to discuss the opioid crisis and what to do about it. Photo: Episcopal Diocese of West Virginia

True, Klusmeyer said, for some people, jail might actually help. Sometimes it keeps inmates away from drugs, especially when the jail provides sobriety-support programs. Drug courts offer alternatives to people charged with drug possession, such as rehab, graduated incentives and supervision rather than simply imprisoning offenders. For others, mental health treatment or institutions are the pathways to recovery. Family support or 12-step programs help others.

“Unfortunately, there’s no one magic bullet to fix it,” he said.

The Rev. Allison DeFoor, canon to the ordinary in the Diocese of Florida, is tackling the problem in a more “top-down” way by advocating for policy change in prison and justice reform and ministering to prisoners, said Sandy Wilson, the diocesan communications director. DeFoor is working with Florida State University’s Project on Accountable Justice and pushing for needle-exchange reform to provide users with clean needles and reduce the transmission of diseases.

This is a problem that affects young and old, rich and poor. Statistics show that many people live in this opioid crisis on some level, either personally or through family or friends. “Many of them see the church as a hotel for saints, and that’s been a problem, isn’t it, that those outside the church feel like they’re not good enough to be inside the church?” Klusmeyer said.

“God knows, we have a lot of work to do.”

— Amy Sowder is a special correspondent for the Episcopal News Service and a freelance writer and editor based in New York City. She can be reached at amysowderepiscopalnews@gmail.com.

Social Menu