Pressure mounts to remove Confederate symbols from Episcopal institutionsPosted Aug 25, 2017 |

|

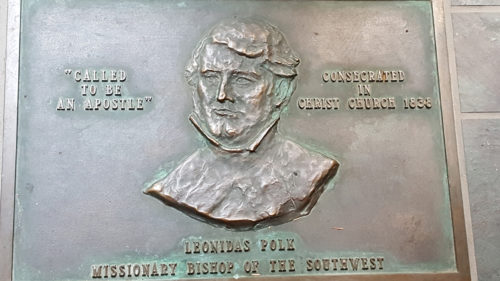

This plaque honoring Leonidas Polk, an Episcopal bishop and Confederate general, is displayed in Christ Church Cathedral in Cincinnati, Ohio. Dean Gail Greenwell says it should be removed or relocated. Photo: Sarah Hartwig/Christ Church Cathedral

[Episcopal News Service] Parishioners who attended Sunday worship at Christ Church Cathedral in Cincinnati, Ohio, on Aug. 20 should not have been surprised that Dean Gail Greenwell’s sermon addressed the issue of racism, given the national outcry over a large white supremacist rally in Virginia the weekend before.

Those hate groups had gathered in defense of a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville. What may have surprised some Cincinnati parishioners is the Confederate symbols in their own cathedral.

Greenwell used her sermon to draw their attention to part of a stained-glass window honoring Lee and a plaque dedicated to Leonidas Polk, an Episcopal bishop and Confederate general. She called for both to be removed.

“The church itself has been complicit in enshrining systems and people who contributed to white supremacy, and they are here in the very corners of this cathedral,” Greenwell said in her sermon.

The growing secular debate over Confederate statues and monuments, amplified by the violence in Charlottesville, also is fueling renewed scrutiny of the numerous Confederate symbols that long have been on display at the Cincinnati cathedral and other Episcopal churches and institutions around the country.

Crew working with the Episcopal Diocese of Long Island saw into one of the plaques commemorating Robert E. Lee at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Brooklyn, New York. Photo: Episcopal Diocese of Long Island

Two plaques honoring Lee had long stood outside a New York City church where he once worshiped and served on the vestry, until a bishop hastily ordered them removed last week.

At Sewanee: The University of the South, a school with Episcopal roots and Confederate connections, administrators say the school has been engaged in an ongoing discussion of Confederate symbols on campus, where a monument to a Confederate general still stands.

Washington National Cathedral in the nation’s capital is deliberating over whether to remove its stained-glass windows honoring Confederate generals Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Depictions of the Confederate battle flag already have been removed from the windows.

Such scrutiny even extends to an Episcopal church’s name. The congregation in Lexington, Virginia, decided in April it would remain as R.E. Lee Memorial Church, but the vestry faces new pressure to reverse that decision.

Vestry members, at their Aug. 21 meeting, approved a joint statement condemning racism and the deadly violence in Charlottesville. They also defended Lee’s reputation as a Christian and his five years as a parishioner after the Civil War. The vestry took no action toward removing Lee’s name from the church, a stance senior warden Woody Sadler supports.

“We would love to be all things to all people, and unfortunately we can’t. And I don’t think any church can,” Sadler told Episcopal News Service in a phone interview.

Just as Episcopal clergy members rallied Aug. 12 in nonviolent solidarity against hatred and bigotry in Charlottesville, Episcopal leaders are turning the focus inward and seeking opportunities for racial reconciliation churchwide in the debate over the legacy of the Confederacy.

“There’s nothing simple about this discernment,” the Rev. Canon Stephanie Spellers, canon to the presiding bishop for evangelism, reconciliation and creation, said in an emailed statement to ENS. “Removing church windows, statues and plaques that honor and valorize the Confederacy may be necessary. I would say they so deny the spirit of Jesus Christ that they have no place in his house.”

But true reconciliation requires more than simply removing Confederate symbols from view, Spellers said.

“Removing them doesn’t change the reason they were originally installed,” she said. “It doesn’t change the way certain groups practically worship those figures. It doesn’t change the fact that our schools are now rife with revisionist history books that whitewash the evil perpetrated against indigenous, black, Asian, Latino and some whites who weren’t white when they got here.”

Charleston massacre was earlier catalyst

Even so, an unprecedented dialogue has occurred in America in the two years since Dylann Roof opened fire June 17, 2015, at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, killing nine people. After Roof’s arrest, details of his fondness for the Confederate flag prompted some Southern leaders to order an end to displaying the flag at statehouses and other public places, a sudden and dramatic reversal after years of resistance to calls for the flag’s removal.

The Episcopal Church’s General Convention also weighed in, passing a resolution in 2015 condemning the Confederate battle flag as “at odds with a faithful witness to the reconciling love of Jesus Christ.” The resolution also advocated the removal of the flag from public display, including at religious institutions.

That resolution’s scope was limited to the flag, but racism has been a regular focus of General Convention for at least four decades. Through its resolutions, the church has committed to “addressing institutional racism inside our Church and in society,” ending “the historic silence and complicity of our church in the sin of racism,” and researching the historic ways the church benefited from slavery.

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry has identified racial reconciliation as one of three priorities during his primacy, and this year, his staff issued guidelines under the title “Becoming Beloved Community” intended to help congregations succeed in their local efforts.

This emphasis on racial reconciliation has aligned the church with people who oppose display of Confederate statues, monuments and other symbols. They argue the Confederacy cannot be absolved for leading the country into a brutal civil war with the goal of preserving slavery, and they say Confederate symbols now are inextricably linked to the racism espoused by the hate groups that rally behind them.

Others, while disavowing white supremacist groups, have cited history and heritage in arguing against removing Confederate monuments. They note slavery is a stain on the lives of many heroes of American history, not just Confederate generals, adding that removing statues succeeds in obscuring the past, not eliminating racial hatred.

Attempts by congregations to bridge such a divide can be painful, but the process also can be healing. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, is a case study.

St. Paul’s, located in the former Confederate capital, was once known as the “Cathedral of the Confederacy.” Lee worshiped there, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis was a member. Until recently, a plaque hung on a wall in the church honoring Davis and featuring the Confederate battle flag.

After the 2015 Charleston shooting, the Rev. Wallace Adams-Riley, St. Paul’s rector, challenged the congregation to think deeply about whether Confederate symbols belonged in their worship space. That challenge grew into the History and Reconciliation Initiative, and through an invitation to discernment, the congregation decided to remove all battle flags but keep family memorials to fallen Confederate soldiers.

“We Southerners have often made it an either-or thing,” Adams-Riley recently told the Daily News Leader in Staunton, Virginia. “That we either recognize our ancestors for their bravery or we get honest about all that was so dark, so terribly dark, about our culture that rested on the back of enslaved men, women and children. But the truth should set us free. We can afford to tell the whole story. What we want is more history, not to erase history.”

Plaques still mark the pews at St. Paul’s where Lee and Davis once sat, and the pair are featured in stained-glass windows.

Stained glass fabricator Dieter Goldkuhle, who worked with his late father to install many of the stained glass windows at Washington National Cathedral, replaces an image of the Confederate battle flag after cathedral leaders decided in 2016 that the symbol of racial supremacy had no place inside the cathedral. Photo: Danielle E. Thomas/Washington National Cathedral

Washington National Cathedral, like St. Paul’s, chose to remove all depictions of the Confederate flag from its stained-glass windows after the Charleston massacre. But the cathedral is only halfway through a two-year process of discerning whether to remove the Lee and Jackson windows also, Dean Randy Hollerith said in a June 30 letter to the congregation.

“These windows, and these questions, have exposed emotions that are raw and sometimes wounds that have not yet healed,” Hollerith wrote. “They have helped to reveal how much we still have to learn as we work toward repairing the breach of racial injustice and building the beloved community.”

A cathedral spokesman said this week the events in Charlottesville have added a sense of urgency to the process.

‘What we choose to revere’

Greenwell, the Cincinnati dean, was more direct in calling for the vestry to re-examine two memorials in the cathedral with the hope they will be removed.

One of them depicts Leonidas Polk, who was consecrated in 1838 in Cincinnati and served as the missionary bishop of the southwest. Polk, one of the founders of Sewanee, was bishop of Louisiana when he served as a Confederate general. He was known to wear his Episcopal vestments over his military uniform, “a thoroughly offensive merge of his professed faith and his fervor to see the institution of slavery endure,” Greenwell said.

Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, is depicted as receiving a blessing from Virginia Bishop William Meade in this stained-glass window at Christ Church Cathedral, Cincinnati, Ohio. Photo: Sarah Hartwig/Christ Church Cathedral

The other memorial, a stained-glass window showing Lee receiving a blessing from Virginia Bishop William Meade, was a gift from a Lee descendant, Greenwell said.

“We need to be very careful, very thoughtful about what we choose to revere on a plaque or put on a pedestal,” she said in her sermon.

The vestry is scheduled to discuss the memorials at its Sept. 13 meeting.

Sewanee, too, embodies the complex task of bridging this divide, given how its heritage, like that of the South, is interwoven with Confederate history.

The university in Sewanee, Tennessee, known in the Episcopal Church for its seminary, was founded in 1857 by several Episcopal dioceses under Polk’s leadership, though the Civil War delayed its opening until 1868. (Polk was killed 1864 as he and other generals scouted Union positions near Marietta, Georgia.)

Should Polk be honored at Sewanee? Even the relocation of a historic portrait of the school founder sparked debate in 2016, though university’s efforts to re-examine Confederate symbols extend beyond Polk and date back more than a decade.

A 2005 New York Times article reported on ways Sewanee and other Southern universities were trying to appeal more to students outside the South. In Sewanee’s case this meant removing controversial symbols, including Confederate battle flags in the chapel and a ceremonial mace given to the university and dedicated to a Ku Klux Klan founder.

Such moves alienated some of the school’s alumni, though traces of the Confederacy remain on campus, such as its monument honoring Edmund Kirby-Smith, a Confederate general who later taught math at Sewanee.

Edmund Kirby-Smith was a Confederate general who later taught mathematics at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee, where this monument to the general is located. Photo: Caroline Carson

Sewanee has removed “many of the most visible and controversial representations of the Confederacy,” Vice Chancellor John M. McCardell Jr. said in a written response to an ENS inquiry.

“It is too easy, however, to get consumed with the metaphor that the Confederate symbols represent and thereby miss the real need to combat hate, bigotry, and racism,” he said. “The University of the South has made intentional and effective strides in the past several years to address these very issues and will continue to do so.”

But what should a church do when its very name is associated with the Confederacy?

Lee had been dead for 33 years when the church in Lexington was renamed R.E. Lee Memorial Church, and some members of the congregation see its identity closely tied to its most famous parishioner.

“Some say he even saved the parish,” Sadler, the senior warden, said.

Changing the name would alienate many members of the congregation, Sadler said, and he dismissed arguments that the name has become a distraction and makes the church less welcoming to those in the community who find Lee offensive.

“I feel that if the congregation wants to keep the name, then that’s what we want to call ourselves,” he said. “And we should not have other people who will never worship in our church … demand that we change what we call ourselves.”

Southwestern Virginia Bishop Mark Bourlakas is among those who warn the name is distracting the congregation from its gospel mission. He plans to discuss the issue during a visit to the Lexington church on Aug. 30.

But Bourlakas, who attended Sewanee in the 1980s when Confederate flags still were displayed in All Saints’ Chapel, also thinks it is important for Americans everywhere to open their minds to the pain such symbols can bring.

“People, especially white people, go along thinking, what’s the harm? It’s just a monument. What’s the harm of this flag? Big deal. It’s been up there forever,” he said, and unfortunately, it takes an outbreak of violence, as in Charleston and Charlottesville, for some people to consider a different perspective.

Spellers hopes the conversations underway in places like Cincinnati, Sewanee and Lexington will be steps on a longer journey toward racial reconciliation.

“Removing the symbols from their current places of honor and using them elsewhere for education and repentance has to be one part of a comprehensive effort to tell the truth, proclaim the dream of God, practice the way of love, and repair the breach in society,” Spellers said, “all of which are necessary to move toward Beloved Community.”

— David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu