Episcopalians, Anglicans have been involved in political actions for decadesPosted Mar 9, 2017 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] Over the years, Episcopalians and Anglicans have lived out the Gospel’s call in many ways, celebrated and unknown. They have taken that call to the streets and into the halls of government, some achieving worldwide notoriety while others might be unknown to large parts of the Church. Here are just a few examples.

To ‘awaken the civic conscience.’

A story is told about how Bishop William T. Manning, who led the Diocese of New York from 1921 to 1946, confronted racism in the church. It begins in 1929 when the Rev. Rollin Dodd became rector of All Souls’ Church at Saint Nicholas Avenue and 114 Street and began to welcome into the church African-Americans who were moving into Harlem, then an all-white neighborhood. The vestry disapproved of the rector’s stance. First, they told him to stop his hospitality, then insisted he resign and then they stopped paying him. When all else failed, they closed the church “for repairs” and filled it with scaffolding.

Manning arrived on a Sunday morning in October 1932, reportedly with New York police and firemen in tow. He ordered a locksmith to break the lock on the gate before the church door and marched in with the rector and a large group of African-Americans to worship. He noted that the vestry had no authority to deny the rector free use of the church and declared that the church would be open “to all the people in the neighborhood who wish to attend its services, without distinction of race or color.”

Manning arrived on a Sunday morning in October 1932, reportedly with New York police and firemen in tow. He ordered a locksmith to break the lock on the gate before the church door and marched in with the rector and a large group of African-Americans to worship. He noted that the vestry had no authority to deny the rector free use of the church and declared that the church would be open “to all the people in the neighborhood who wish to attend its services, without distinction of race or color.”

Manning spoke up when he saw wrongs being committed and people taking the wrong directions, whether theologically or civically. He was warning against Nazism, fascism and Communism in 1937, saying in a Thanksgiving speech to the New York Kiwanis Club, “they all stand alike for the extinction of liberty.”

In July 1942, he took to the pulpit of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine to dispute the idea that it was un-Christian to pray for victory in the world war that was raging. The bishop declared that it was “not only right but our bounden [sic] duty to pray for victory.”

“You know that it is God’s will that this should be a world of liberty and brotherhood and justice,” said the bishop who had served as a chaplain in World War I.

After the end of the war, Manning said on the eve of his 82nd birthday, and about a year before his death, that he favored universal military training. Saying the world needed standing armies in the same way New York City needed a police force, the then-retired British-born bishop said: “false pacifism” in the U.S., Britain and France had led Hitler and Mussolini to think that they could carry out their aggressions.

Manning was a frequent contributor to the letters to the editor column of The New York Times, which he used as a forum to weigh in on such issues as a then-controversial federal measure in 1941 to force married couples to file joint income tax returns.

The idea, he wrote, “turns its back upon all the progress that has been made in the status of women in recent decades and belongs to the age when women were not regarded as people, and a married woman was not allowed to hold property in her own right.”

Ever a man of his times, he added that “those who have been divorced or who have refrained from marriage perhaps for selfish reasons, or who live in immoral sexual relationships, will be called upon to pay far less to the government than the married couples who in their faithfulness to the obligations of the home and family are the strength and mainstay of our life as a nation.”

A man of action and not just words, Manning organized a union of all New York church organizations in 1937 to “awaken the civic conscience” to respond to slum living conditions in the city.

Manning’s public stances sometimes earned him critics. In 1937, he frequently preached and spoke in other forums against an anti-Semitic idea that Jesus came to the world to save it from Jews and, thus, that true Christianity had to be anti-Semitic.

Proving that the current public discourse has no corner on the lack of civility, one proponent, Julius Streicher, called Manning “a pseudo-priest, a wolf in sheep’s clothing and a two-fold child of hell.” In return, the bishop promised to keep speaking “against the persecution of the Jews or anybody else in Germany or anywhere and against national or religious persecution or discrimination of any sort.”

The New York Times’ obituary for Manning, describing more aspects of his Christian activism, is here.

‘I came to Washington to serve God, FDR, and millions of forgotten, plain, common workingmen.’

Frances Perkins’ faith informed her entire life. Perkins, who lived from April 10, 1880, to May 14, 1965, was a sociologist and workers-rights advocate. She served as U.S. secretary of labor from 1933 to 1945, the first woman appointed to a Cabinet position.

Christened Fannie Coralie Perkins, she changed her name to Frances when she was confirmed in the Episcopal Church in 1905 at age 25. She had encountered the Church while working in Chicago teaching chemistry and volunteering in settlement houses, including Hull House.

Christened Fannie Coralie Perkins, she changed her name to Frances when she was confirmed in the Episcopal Church in 1905 at age 25. She had encountered the Church while working in Chicago teaching chemistry and volunteering in settlement houses, including Hull House.

At 31, working for the Factory Investigation Commission in New York City, she witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist fire that killed 146 people, primarily young women factory workers. That experience galvanized her career as an advocate for workers.

Perkins became known across New York State as head of the New York Consumers League in 1910. She expanded factory investigations, reduced the workweek for women to 48 hours and championed minimum wage and unemployment insurance laws. She worked vigorously to put an end to child labor and to provide safety for women workers.

Her work brought her to the attention of newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who appointed her to his cabinet. During her term, Perkins helped implement many aspects of the New Deal. She was largely responsible for the adoption of Social Security, unemployment insurance, federal laws regulating child labor and adoption of the federal minimum wage.

She helped set overtime laws for American workers and define the standard 40-hour workweek. Perkins formed governmental policy for working with labor unions and helped to alleviate strikes by way of the United States Conciliation Service.

Throughout her 12 years as secretary, she took a monthly retreat with the All Saints Sisters of the Poor, with whom she was a lay associate. “I came to Washington to serve God, FDR, and millions of forgotten, plain, common workingmen,” she said. Her theology of generosity informed her professional life and, in turn, transformed the lives of millions of Americans.

“The technique of administration in a democracy is not easy…The statute law and the natural law, the law of God, must be somehow or other blended together, and fairness and decency and patience must prevail,” she said in 1939.

Perkins remained active in teaching, in social justice advocacy and in the mission of the Episcopal Church until her death in 1965.

The Episcopal Church remembers Perkins on May 13. She won the worldly honor of the Golden Halo in the 2013 Lent Madness competition, defeating St. Luke. Perkins had Maine ties, and fellow Mainer Heidi Schott promoted Perkins for Lent Madness with this article.

‘You are a child of God and I am a child of God, and because you are suffering, I must suffer, too’

Jonathan Daniels paid the ultimate price for living out the Gospel. Daniels, 26, was martyred on Aug. 20, 1965, when a Lowndes County, Alabama, employee fired a shotgun from a nearly point-blank range at his chest. In dying, Daniels saved then-17-year-old Ruby Sales when he pulled her from in front of him. Daniels, a white seminarian from Episcopal Theological School, now known as Episcopal Divinity School, and Sales were fellow civil-rights workers in a part of the state that he once said: “need[ed] the life and witness of militant saints.”

Daniels, Sales, another black demonstrator Joyce Bailey, and Roman Catholic priest Richard Morrisroe had just spent six hot August days in the local jail. Police had arrested them for being part of a protest outside of businesses in Fort Deposit. They wanted to call attention to discriminatory hiring practices, unequal treatment of customers and price gouging. The jail had no showers and no toilets, much less air conditioning.

Daniels, Sales, another black demonstrator Joyce Bailey, and Roman Catholic priest Richard Morrisroe had just spent six hot August days in the local jail. Police had arrested them for being part of a protest outside of businesses in Fort Deposit. They wanted to call attention to discriminatory hiring practices, unequal treatment of customers and price gouging. The jail had no showers and no toilets, much less air conditioning.

Then the jailers inexplicably unlocked all the doors and told the prisoners they were free to go. No one was waiting to pick them up, so it was clear that none of their friends had posted bail. It felt like a set-up.

While waiting for a ride but ordered off jail property in Hayneville, they walked to buy soda for the group at Varner’s Cash Store, about 50 yards from the jail. Coleman, a county special deputy wielding a 12-gauge automatic pump shotgun, stood on the concrete pad outside the store. He crudely ordered them off the property.

“Things happened so fast,” Sales recalled years later. “The next thing I know there was a pull and I fall back. And there was a shotgun blast. And another shotgun blast. I heard Father Morrisroe, moaning for water.”

Coleman, a county engineer and a member of one of the oldest white families in Lowndes County, had leveled his gun and fired, blowing Daniels backward. Daniels lay motionless on the ground. Morrisroe retreated, taking Bailey by the hand. Coleman shot him in the back. He required hours of surgery to survive.

Forty days later, an all-white jury acquitted Coleman of Daniels’ murder and shook hands with him as he left the courthouse. Then-Presiding Bishop John Hines said that what Coleman’s acquittal showed “about the likelihood of minorities securing even-handed justice in some parts of this country should jar the conscience of all men who still believe in the concept of justice in this land of hope.”

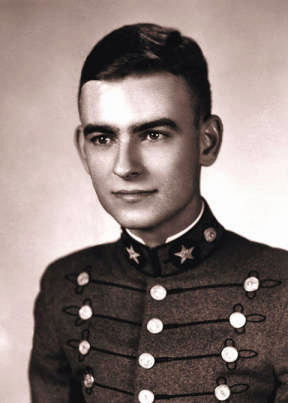

Daniels, who was valedictorian of the Class of 1961 at Virginia Military Institute, had first come to Alabama in March 1965 with fellow seminarian Judith Upham in response to a call from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. for Northern clergy to come south in support of the movement. They lived with local black families as they worked for voter registration and other avenues towards equal rights. “Sometimes we take to the streets, sometimes we yawn through interminable meetings … Sometimes we confront the posse, sometimes we hold a child,” Daniels wrote, describing their daily work.

Daniels, who went back with Upham to seminary to take final exams and to visit his family in Keene, New Hampshire, returned to Alabama for the summer of 1965. Upham spent that summer fulfilling the school’s clinical pastoral education requirement at a state mental hospital in St. Louis, Missouri.

“I had been blinded by what I saw here (and elsewhere), and the road to Damascus led, for me, back here,” Daniels wrote about his return to Lowndes County.

Daniels is one of six 20th-century individual martyrs honored in the church’s most recently proposed calendar of commemorations, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, and the only Episcopalian. His feast day is Aug. 14, the day of his imprisonment. (The calendar also honors three groups of modern-day martyrs.)

The New York Times report of Daniels’ murder is here.

‘It is a religious obligation to oppose racism. If you do not, you disobey God.’

Desmond Tutu brought down a government and a system of racism that government had enshrined in law. He did not do it alone, but many say they could not have done it without him.

Moreover, in the midst of the often bloody struggle to end apartheid in South Africa, Tutu constantly called for non-violent action, condemning violence by both the government and by anti-apartheid groups.

Tutu was a prominent leader in the Anglican Church in South Africa when students in Soweto Township rebelled in June 1976 against the decision to use Afrikaans, along with English, as the language of instruction in their schools. What had been a peaceful demonstration by as many as 20,000 students turned deadly when police fired live ammunition into the crowd. The world was shocked, and rebellion against apartheid, which had become the law of the land in 1948, spread throughout South Africa.

Tutu was a prominent leader in the Anglican Church in South Africa when students in Soweto Township rebelled in June 1976 against the decision to use Afrikaans, along with English, as the language of instruction in their schools. What had been a peaceful demonstration by as many as 20,000 students turned deadly when police fired live ammunition into the crowd. The world was shocked, and rebellion against apartheid, which had become the law of the land in 1948, spread throughout South Africa.

Police jailed Tutu briefly in 1980 after they arrested him during a protest march, and he risked a similar sentence years later when he called on South Africans to boycott municipal elections. In 1983, he challenged a governmental attempt to change the national constitution to defend against anti-apartheid efforts.

South Africans elected Tutu in 1986 to be the first Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, and thus the leader of the Anglican Church in Southern Africa. From that pulpit, he continued to lead South Africans and the world in opposing apartheid. He praised the government for moderating its stance in the late 1980s but pushed for an end to the system of racial segregation and oppression.

Episcopalians supported the anti-apartheid campaign in many ways, both as individuals and as the church. In 1971, then-Presiding Bishop John Hines came to General Motors Corp.’s annual meeting to present a shareholder resolution filed by the Church requesting that GM stop doing business with South Africa. He shocked GM executives, many of whom were Episcopalians. The leadership of Hines and the Church helped to prod companies and investors to divest themselves of their South African holdings and started the socially responsible investing movement.

“We owe you an enormous debt of gratitude,” Tutu told a banquet held in 1991 to honor the 20th anniversary of the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility, which the Episcopal Church helped get off the ground.

Still, it wasn’t until late April 1994, that South Africa held its first non-racial democratic elections.

Even as he compared apartheid to Nazism, Tutu always pleaded for justice and reconciliation in South Africa. Many credit Tutu’s stances with helping the country avoid an all-out race war. He earned the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize for his leadership. Tutu always framed his advocacy as religious, not political. He told the government of the time that its racist approach defied the will of God and for that reason could not succeed.

In 1994, Tutu spoke in the Diocese of Southern Ohio about changes occurring in South Africa. “We have succeeded — we have achieved our goal — and we have got this extraordinary thing which is taking place in our country — in many ways, inexplicable,” he said. “But for those who are believers, obviously, in the end it is not inexplicable. It is the intervention of a wonderful God.”

In Cincinnati, he addressed 225 leaders of a citywide Summit on Racism, telling them, “It is a religious obligation to oppose racism. If you do not, you disobey God.”

Tutu went on to chair South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission meant to expose the stories of apartheid-era crimes. The restorative-justice body recommended whether individuals who confessed their crimes should receive amnesty. The archbishop once said he was “appalled at the evil we have uncovered.” Although the commission was criticized for being too soft on some people, Tutu used the commission model to help other nations and groups, including Northern Ireland, confront their conflicts.

Since the apartheid years, Tutu has campaigned for human rights and fought HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia. He vocally opposed the Iraq War, at one point calling for then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair and U.S. President George W. Bush to stand trial for their roles in starting the war.

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is senior editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu