Standing Rock camps face another deadline due to melting snow, changing tacticsLocal Episcopalians join tribe's call for march on Washington, D.C. next monthPosted Feb 17, 2017 |

|

Crystal Houser, 30, of Klamath Falls, Oregon, bags excess blankets for delivery to nearby communities Feb. 8 while helping to clean up the opposition camp against the Dakota Access oil pipeline near Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Photo: REUTERS/Terray Sylvester

[Episcopal News Service] Standing alongside the road in Solen, North Dakota, Feb. 17 and looking out over the Cannonball River, the Rev. John Floberg declared the weather too hot.

“It’s 43 degrees,” he said during a telephone interview, as a car sped by at midmorning.

The day before the temperature was above 50.

Weather like that is enough to speed the melting of the more than 40 inches of snow that have fallen on the Standing Rock Sioux Nation this winter. It prompts predictions of ice jams in the Cannonball River next week. It’s enough to hasten the cleaning up and breaking down of the Oceti Sakowin protest camp that has been filled with people there to protect the waters of the Missouri and Cannonball from what they see as the threat of pollution from the nearly complete Dakota Access Pipeline.

Federal and state officials, as well as the tribe, have set Feb. 22 as the latest date for the camps to close. Reducing the size of the camps, or relocating them, has been a multi-week effort. Tribal officials earlier had said that the harshness of the winter made the camps unsafe. Now, they are worried about the safety of the several hundred still camped there when the snow melts and the Missouri and Cannonball run high. They are also worried that floodwater will sweep debris from the camps into the rivers, polluting them when the ultimate goal of the encampment was to prevent pollution. And, they are worried about talk of last stands and people staying until the bitter end.

The majority of the northeastern portion of Oceti Sakowin Camp has been cleaned up and many sections of camp have been cleared. “We are cooperatively working together to clean camp up in a good and timely way,” organizers said Feb. 16. Photo: Oceti Sakowin Camp via Facebook

However, Oceti Sakowin residents have been cleaning up the land and there is a systematic plan for that work. Camp residents and officials who wanted access to the camp to judge how much clean-up work remains held a tense meeting Feb. 16. Floberg and others are concerned about this next round of attempts to shut down the camps, hoping for a peaceful reaction from both officials and residents. What some call an over-militarized law enforcement response and instances of provocation by self-described water protectors at times have marred the months-long encampment.

Oceti Sakowin is flooded this week. Water is standing on the camp’s frozen ground. Just “squishy under your feet” in some places, said Floberg, but close to a foot of water in other places.

State officials warn of river contamination https://t.co/ylfp6GC7Cq pic.twitter.com/hUT7HyZ6cM

— The Bismarck Tribune (@bistrib) February 15, 2017

It is just enough to make the ground muddy but not enough to bog down the skip steer that he is using to help in the cleanup. Floberg, using the small, engine-powered machine with lift arms to move heavy loads, has recovered about 5,000 pounds of donated but unclaimed rice and another 5,000 pounds of flour that are salvageable for reservation food pantries. He loads such material into a trailer hitched to his pickup, which he drives in four-wheel drive low gear through 8 inches of mud up the hill to the highway.

“You keep feeling for momentum, but you don’t want to start spinning your wheels,” said Floberg, priest-in-charge of Episcopal Church congregations on the North Dakota side of Standing Rock, who added that “all of these skills I learned in seminary.”

The Episcopal Church has advocated with the Sioux Nation about the Dakota Access Pipeline since summer 2016. Local Episcopalians have also provided a ministry of presence in and around Cannon Ball, North Dakota, the focal point for groups of water protectors that gathered near the proposed crossing. That work and everything else that followed, Floberg said, “is our vocation as Christians.”

The work does not come without risk, he said, especially to the Episcopal Church’s reputation. “There is a risk to the reputation to our congregations in predominantly white communities around the state; how they will be viewed because of the actions we take here on Standing Rock,” Floberg said.

Then there are the practical implications of that risk. For instance, an engineer from the local power cooperative has been slow to help Episcopalians install an array of solar panels purchased with a United Thank Offering grant because he is “upset with the Episcopal Church for having gotten involved in this protest.”

Moreover, Floberg said, the Episcopal Church’s long-standing ministry to, among and with the people on Standing Rock has paid a price. “There’s only so many hours in the day so who’s not getting visited in the hospital?” he explained. “What else is not being accomplished or attended to that otherwise would have been?”

Floberg said he continues to be grateful for the support the local Episcopal community has gotten from the wider church in terms of both solidarity and donations.

The work of the Episcopal Church and local Episcopalians is taking place against the backdrop of a constantly changing legal and political landscape. The Army on Feb. 17 formally ended a month-old environmental impact study of the pipeline’s disputed crossing. That study was eight days old when newly inaugurated President Donald Trump called for a rapid completion of the pipeline. The Army gave Texas-based developer Energy Transfer Partners permission for the crossing on Feb. 8.

The lights of the drill pad built for the final portion of the Dakota Access Pipeline can been seen from Oceti Sakowin Camp. Photo: Oceti Sakowin Camp via Facebook

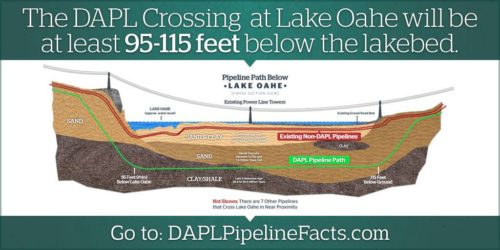

The remaining work on the pipeline involves pushing pipe under the Missouri River at Lake Oahe just north of the Standing Rock Reservation. The pipeline company set up a drill pad very near the proposed crossing point, which is upstream from the tribe’s reservation boundaries. The tribe has water, treaty fishing and hunting rights in the lake. Workers have drilled entry and exit holes for the crossing, and filled the pipeline with oil leading up to the lake in anticipation of finishing the project, according to the Associated Press.

The Standing Rock and neighboring Cheyenne River Sioux also are fighting the pipeline work in court, with the next hearing set for Feb. 28. Standing Rock officials have been saying for weeks that they must wage the fight against the pipeline in the courts, not on the land in North Dakota.

“Don’t confuse the Camp with the movement or its goals,” Floberg said in a Feb. 16 Facebook post. “Keeping the Camps open was never the goal. Keeping clean water is the goal. In this particular place and time, respecting Treaty Obligations is the main road to that goal.”

Related to the changing venues for the movement, Standing Rock has called for a March 10 march in Washington, D.C. Organizers are still working out the details but the plan is for people to gather on or near the National Mall and march to a place near the White House.

Floberg is amplifying the tribe’s call by asking Episcopalians to join that march. He has established a Facebook page, Standing Rock Rocks the Mall, where details will be posted. Floberg is also organizing a prayer service for the night before the march at Washington National Cathedral. Advocacy in congressional offices is also part of the plan.

Dakota Access Pipeline developers have been publicizing this infographic to show the engineering of the pipeline’s last stretch. Photo: DAPLPipelinefacts.com

The 1,172-mile, 30-inch diameter pipeline is poised to carry up to 470,000 barrels of oil a day from the Bakken oil field in northwestern North Dakota – through South Dakota and Iowa – to Illinois, where it will be shipped to refineries. The pipeline was to pass within one-half mile of the Standing Rock Reservation, and Sioux tribal leaders repeatedly expressed concerns over the potential for an oil spill that would damage the reservation’s water supply and the threat the pipeline posed to sacred sites and treaty rights. Energy Transfer Partners says it will be safe and better than transporting oil by truck or railcar.

Also on Feb. 17, CalPERS, the $300 billion California public employee pension fund, said it joined more than 120 other investors in calling on banks funding the pipeline to get it routed away from Native American land.

“We are concerned that if DAPL’s projected route moves forward, the result will almost certainly be an escalation of conflict and unrest as well as possible contamination of the water supply,” the letter says. “Banks with financial ties to the Dakota Access pipeline may be implicated in these controversies and may face long-term brand and reputational damage resulting from consumer boycotts and possible legal liability. As major shareowners of these banks, we are very concerned about the financial risks this poses to the investments we oversee and to those whom we serve as fiduciaries.”

The list of banks and investors, including four New York City public employee pension funds and a number of religious groups, is here. In all, the signatories control a total of $653 billion in assets.

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is senior editor and reporter for the Episcopal News

Social Menu