After presidential power shifts, Episcopalians ask: How should we pray?Posted Jan 23, 2017 |

|

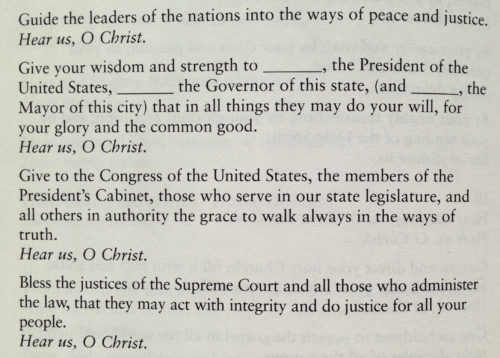

The Book of Common Prayer calls for Episcopalians to pray for the nation and those in authority (page 359). Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] When Bishop Jeff Lee wrote to Episcopalians in the Diocese of Chicago after the November election, he asked that they pray for Donald Trump, as well as all elected officials and for the church.

One recipient asked him to stop telling people to admire the president-elect. Such admiration was not what Lee was after, but only prayer, he told the recipient. Yet, he said in an interview with Episcopal News Service, the person’s reaction gave him a clue about the intensity of the reactions to Trump’s election.

The dialogue between Lee and a member of his diocese is not an isolated incident. Since Trump’s election in November, many Episcopalians have asked what it means to pray for the 45th U.S. president during public worship, how to do it, and, for some, even whether to offer such prayers at all.

For some Episcopalians, there is no debate: they will pray for Trump whether they are happy to have him as president or not. While some congregations that are in the habit of praying for the president by name might end that practice; for others, it is a foregone conclusion that such specificity will continue.

In social media and congregational discussions, other Episcopalians make the distinction between praying for the office of the president, not the individual. Some say that they cannot abide Trump being named in the liturgy because hearing his name triggers trauma for some congregants considering his past sexual, misogynist and racial comments, and general behavior during the campaign and since. Still others say that one cannot separate praying for the office and the officeholder; they know who is in that office whether or not they name him.

Does praying for the president imply blessing, commending or accepting that person’s behavior or politics, others wonder. Or is praying for God to guide this incoming president or any president exactly what Christians ought to be doing?

What the Book of Common Prayer and the Bible say

The Book of Common Prayer is clear, in as far as it goes. The second of the six rubrics that standardize the Prayers of the People in the Rite II Eucharistic liturgy (page 359) requires petitions for “the Nation and all in authority.” The rubrics do not require leaders to be prayed for by name.

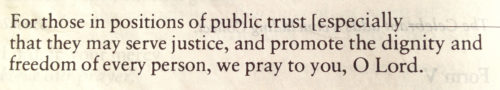

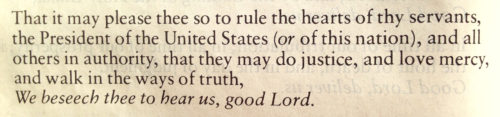

Of the six suggested Rite II forms for those prayers, only a bidding in Form I makes specific mention of “our President.” Form V is the only one that gives an option of praying for “those in positions of public trust” by name.

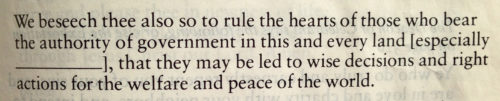

Holy Eucharist Rite I’s single Prayers of the People form gives the option of praying by name for “those who bear the authority of government.”

Presumably, congregations that adapt the prayer book’s forms or use other forms for the Prayers of the People follow the categories listed in the prayer book rubrics.

The Book of Common Prayer also contains prayers for use in any liturgy or for private prayer, including nine “Prayers for National Life” (pages 821-823) and two “Thanksgivings for National Life” (pages 838-839).

The first of the six forms of the Prayers of the People in Rite II’s Eucharistic liturgy includes a petition for the president (page 384). Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

Many Episcopalians root their Prayers of the People decisions in Scripture. They reference Matthew 5:43-48 in which Jesus tells his followers to “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

They also cite Paul’s admonition to the Romans not to be overcome by evil but to overcome evil with good (Romans 12:21), as well as the next verse (Romans 13:1) in which Paul says Christians should obey “the governing authorities.” Some point to 1 Timothy 2:1-4 in which the author calls on Christians to pray for “kings and all who are in high positions.”

Is this a test?

A thread running through many of these discussions is whether this prayer debate is a test of Episcopalians’ faithfulness to the Gospel.

“This is when religion gets real,” Presiding Bishop Michael Curry told Episcopal News Service in a recent interview. When facing questions such as this, Curry said Christians must confront their understanding of their identity in Christ.

“If we are living into being a part of the movement of Jesus of Nazareth, following his footsteps and his spirit, his way; if that’s who we are; and, if that’s what baptism is about, then I’ve got to be better than myself even when I don’t want to be,” he said, including honoring the scriptural imperative to pray for those who have wronged you, or worse.

“When we are praying for Donald or Barack … we’re praying for their well-being, to be sure as people, but we’re praying for their leadership; that they will lead in justice, that they will lead in goodness,” he said.

The fifth of the six forms of the Rite II Prayers of the People includes an option to name “those in positions of public trust” (page 390). Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

The Rev. Devon Anderson, rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in Excelsior, Minnesota, told ENS that the debate over the Prayers of the People also goes to the heart of Anglican/Episcopal theology about corporate prayer.

“When we come to the altar to pray on Sunday morning, we pray with one voice. We pray the same words, we sing the same hymns, we cup our hands and receive the same bread. Most importantly, we pray for justice,” Anderson said. “Even the prayers that pray for our elected leaders by name have within them prayers for justice.”

Those prayers call upon elected officials to work for the common good with an eye toward justice and a preference for the poor, she said. “All leaders – no matter their platform, fallibilities, exploits, abuses or policies – are in need of those prayers,” Anderson added.

Praying or protesting?

Curry told ENS that praying for leaders and challenging them to change are not mutually exclusive. “I grew up having to pray for leaders that were encouraging Jim Crow segregation and I was the one being segregated, but we did it anyway,” he said.

During the civil rights movement, Curry said, people “prayed and protested at the same time.”

“We got on our knees in church and prayed for them, and then we got up off our knees and we marched on Washington,” he said.

Jack Douglas said he has prayed daily for previous presidents and he will pray for Trump. “This does not mean that I won’t criticize,” wrote Douglas, who lives in Fayetteville, Arkansas. “I’ll always criticize, but I’ll also pray.”

Anderson, who also chairs the Episcopal Church’s Standing Commission on Liturgy and Music, believes “church communities must model the kind of justice and engagement we are demanding of our elected leaders,” starting “with corporate prayer which inspires prophetic witness and ministry in our communities on behalf of marginalized people.”

While she understands the impulse of a faith community that is unified in its political ideology to refuse to pray for the president by name, Anderson said she serves “a politically diverse congregation that is not of one mind politically.” It also has a 28-year refugee resettlement ministry, a long-standing partnership with indigenous communities and a commitment to racial reconciliation.

“We have to be very careful to continue to offer corporate worship that unifies us rather than divides. We will continue to pray for our elected leaders (by name) when the Book of Common Prayer calls for it,” she said. “To me, that is an act of resistance against division.”

Trinity also will redouble its outreach efforts in the coming days and years “because the Gospel calls us to those ministries,” she said.

The traditionally worded Rite I Eucharistic liturgy gives the option of praying by name for those “who bear the authority of government” (page 329). Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

For Anderson, the question “is way deeper than proper names in Prayers of the People.”

“The question is: How far are we willing to go to help bring about what we are praying for? How much of our hearts (and our time and our resources) are set on the real work and engagement it will take to set things that are wrong in our country, right again?” she told ENS.

What’s in a name?

The Rev. Elizabeth Kaeton, a longtime activist inside and outside the Episcopal Church who works as a hospice chaplain in Delaware, cannot countenance praying for Trump by name during the liturgy. Praying for Trump by name is different than publicly praying for Barack Obama or George W. Bush, she told ENS.

“He has said things that are at odds with the founding principles of this nation: freedom and justice for all. He does not ascribe to that,” Kaeton said, adding that she sees no evidence that Trump respects the dignity of every human being or seeks to serve Christ in all people as the Baptismal Covenant calls for.

“How do we as a corporate body pray for someone who is antithetical to our country and our Christian beliefs without at least having a conversation about what that means?” she asked.

A recent discussion on ENS’ Facebook page exemplified the division this question raises. For example, Judy Schroder Niederman wrote that, because of how she said Trump “ridicules and bullies others, how he lies, how he threatens,” she “cannot and will not utter that man’s name. Not yet emotionally able to pray for him. I will pray for the office of the presidency.”

Alynn Beimford replied, saying for eight years she could not invoke Barack Obama’s name during worship but will “joyfully” use Trump’s.

The Rev. Mike Kinman, rector of All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, California, cited the reaction that Trump’s name stirs in some people in his decision to have the parish stop praying for the president by name.

“We are rightly charged with praying for our leaders,” Kinman wrote. “But we are also charged with keeping the worshipping community, while certainly not challenge-free, a place of safety from harm.”

Kinman likened praying for Trump to requiring an abused woman to pray by name for the person who abused her. “It’s not that the abuser doesn’t need prayer – certainly the opposite – but prayer should never be a trauma-causing act,” he said.

He pledged to listen to the congregation and pray about his decision.

Kaeton said she hopes this debate “opens up a discussion in congregations as well as nationally about prayer, about the efficacy and the purpose of prayer, and the difference between private prayer and public prayer.”

“I hope it gets congregations looking at what they’re doing in their liturgy, and how they’re praying the Prayers of the People and who decides that. Are we just acquiescing to what clergy say?”

The Great Litany (page 148), which many Episcopal congregations will use on the First Sunday in Lent, includes a petition for the U.S. president and is specific about the prayer’s intention. Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

The Rev. Michael Arase-Barham, vicar of Holy Family Episcopal Church in Half Moon Bay, California, and Good Shepherd Episcopal Church in nearby Belmont, agreed such a discussion is necessary.

“My immediate instinct is to say I am fascinated that we are talking about whether or not we should be praying instead of praying together,” he told ENS. “However, part of the problem is that, perhaps, we haven’t talked enough about how to pray for our enemies. It’s harder to start praying for your enemies when you have them and it is no longer theoretical.”

Following the conversations on social media, Arase-Barham said he has been struck by “how easily we can look down our noses at each other about this. It seems me that prayer ought to be making all of us a little more humble and open towards one another. In some ways, we’re making enemies of our friends on Facebook.”

“How can we pray for Trump if we can’t discuss this civilly and spiritually?” he asked.

The mysteriously transforming power of prayer

Arase-Barham suggested congregations ought to talk about the reality that the petitions in the Prayers of the People leave enough room for an individual’s intentions to join with other voices in the praying body. For instance, he said, he focused on different things while praying for George W. Bush or Barack Obama during the liturgy.

“The spirit is still able to work in each person in that room praying that prayer, and God is able to work in spite of our desired outcomes through us and through that prayer,” Arase-Barham said.

Curry told ENS “to pray for those who are in leadership is to actually unleash energy that absolutely has its source in God and that may touch the human spirit in some way.”

The prayer is “not avoiding the reality” for the issues involved but, he said, “it’s actually going deeper; it has a way of freeing the person who is praying from the destructive power of a destructive relationship.”

An optional version of the Great Litany found in the authorized “Enriching Our Worship” series includes petitions for all three branches of the U.S. government, and calls for naming the president. Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

The Rev. Kim Hobby, pastor of Christ Church Episcopal in South Pittsburg, Tennessee, was among those commenting on the ENS website about the nature of prayer. “Prayer changes things, and the first thing it changes is the one who prays,” she wrote. “True prayer changes our hearts of fear and hatred to hearts of courage and love, despite our human instincts. I pray that the hearts of all our leaders, including the president-elect, will be opened to see, hear, and respond compassionately and respectfully to all people at all times and in all places.”

Lee, the bishop of Chicago, would agree. “Prayer is, first and foremost, not about asking God to rearrange the universe according to my specifications, but asking God to rearrange me,” he told ENS.

In an interview with ENS, the Very Rev. Randolph Hollerith, dean of Washington National Cathedral, said Episcopalians “don’t look at prayer as magic.”

“Our prayers are our way of trying to align ourselves to God and to focus ourselves a little bit more into what God may want for us,” he said. “If I believe that God loves every human being to their core; that God loves every human being infinitely, then how can I just pray for those people I agree with when I know that God loves that person I disagree with to a depth I can’t even understand?”

Read more about it

- Time magazine has published Presiding Bishop Michael Curry’s “Why We Must Pray for Donald Trump.”

- Diocese of Vermont Bishop Tom Ely has issued “A Statement in Support of Prayer & Reconciliation.”

- Diocese of Missouri Bishop Wayne Smith has written a blog post “Praying for a president by name.”

- The Very Rev. Michael Sniffen, dean of Cathedral of the Incarnation in Garden City, New York, has written “Prayers for the President: What’s in a Name?”

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu