As election draws near, preachers feel the gospel’s challengePosted Oct 17, 2016 |

|

In the final weeks before the Nov. 8 general election preachers are facing the challenge of speaking a word of truth and reconciliation into the season’s heated rhetoric. Photo illustration: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] Preaching can be challenging at any time, but it is especially so during an election season and the remaining days of the 2016 U.S. presidential election are proving exceptionally fraught for some preachers.

“There’s weightiness and a kind of heaviness that everyone is bringing to this time,” Diocese of Washington Bishop Mariann Budde said in an interview with Episcopal News Service.

Many preachers want to address the election and its impact on society; many of their congregants want or expect them to do so, but others do not. Beyond navigating the thicket of regulations governing the political activities of nonprofit organizations, including churches, there is the often-asked question of whether political issues belong in the pulpit.

Internal Revenue Service regulations prevent religious organizations from supporting or opposing any candidate, political party or political action committee. Some congregants still wonder if their priests will make such endorsements.

The Very Rev. W. H. Mebane, interim dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Buffalo, New York, explicitly tells his parishioners “I’m not going to do that in a sermon or in the announcement period.”

But, Mebane, who recently supported San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s national anthem protest by preaching while wearing a replica of his jersey, is known for connecting the gospel to the events and concerns of society.

“People accuse me all the time of preaching politics,” Mebane told Episcopal News Service. “My response is always I have never preached a political sermon in my life. I have preached the gospel of Jesus Christ, which can sound awfully political.”

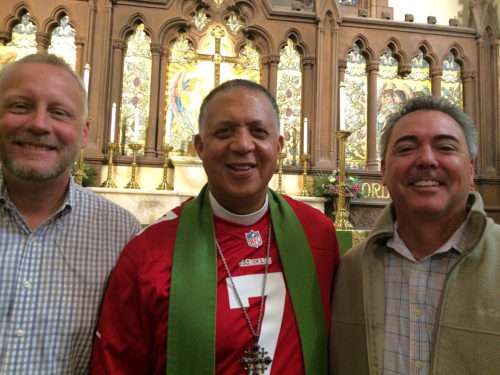

The Very Rev. W. H. Mebane, interim dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Buffalo, New York, recently preached a sermon exploring San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s national anthem protest. Ohio friends John Lauro, left, and Scott Williams, right, came to hear him. Photo: St. Paul’s Cathedral

Preaching the gospel can mean talking about what attributes Christians ought to look for in their potential political leaders. Mebane’s list of traits is anchored in his self-proclaimed “manifesto” found in Matthew 25:35-36 of feeding the hungry, aiding the poor, caring for the sick and visiting prisoners.

When you preach the gospel, said the Rev. Bill Brosend, professor of New Testament and preaching at the University of the South’s School of Theology, people will know where you stand on the political issues of the day.

“If you think they don’t know how you voted in the last election, you are wrong,” he said. “Don’t pretend to a neutrality that doesn’t exist. You did vote for somebody and it probably comes out not just in your sermons but throughout your ministry”

The challenge to the preacher is to find ways to articulate his or her motivations in a way that “invites conversation, allows for difference and encourages everyone to think about how their faith applies to the decisions they make about who to vote for,” he said.

Budde would agree. Well-known in her diocese and beyond for her stands on issues such as racial justice and gun violence, Budde often preaches and writes about the political issues on her mind. However, that outspokenness can make preaching even more challenging.

“Sometimes,” she said. “I just want to be counter type so that I can draw in other voices, and to not be completely dismissed as I open my mouth by the people I might be able to influence if I come at it from a different angle.

“At some level, I’m pretty sure I disappoint somebody every day.”

Budde, who in her role as bishop preaches to a different congregation nearly every Sunday, said she strives to strike a balance that is not “constantly condemning” the direction of this presidential election season, but that can also invite a conversation about “who are we as a nation” right now.

To preach in this manner requires a relationship rooted in generosity between the preacher and her congregation, said the Rev. Pamela Dolan, rector of Church of the Good Shepherd in Town and Country, Missouri, west of St. Louis.

Dolan said she hopes that any preacher’s listeners would practice a stance that she is working to cultivate in herself during this fraught political season. “To not assume I know another person’s motives, especially if I am tempted to ascribe negative motivations,” is how she describes it.

“To take as a baseline that either I can assume that the person preaching wants the best for me and the congregation, or at the very least is not coming at it trying to be hurtful and divisive,” she added.

The Rev. Emily Mellott, rector of Calvary Church in Lombard, Illinois, agreed that solid relationships allow for disagreements without divisions. With relationships based in ministry and love, political disagreements have a better chance of not bothering people because everyone trusts that the person with whom you disagree “is going to show up in the hospital with communion when you’re sick,” she said.

That said, Mellott argued that “to preach the gospel and to preach the gospel in conversation with current events and with the experience that people in the church are having is absolutely political.” In her preaching, she is “talking about how the gospel engages with the news we read and see and hear.”

For preachers, Oct. 9 was a case in point. The news that day was “completely consumed,” Brosend said, by the pending debate that night with Hillary Clinton and the video of presidential candidate Donald Trump’s demeaning comments about women. “To pretend that that wasn’t what everybody was talking about just before the prelude and what they’re going to talk about at coffee hour is craziness,” he said.

Thus, the homiletical question, as Brosend often puts it, of “what does the holy spirit want the people of God to hear from these texts on this occasion?” took on many unexpected dimensions. The day’s Gospel (Luke 17:11-19) was the story about Jesus healing 10 lepers by sending them on their way to Jerusalem and telling them to show themselves to the priest there. Only one, a Samaritan, came back to thank Jesus.

Brosend said he asked the question of which response was faithful; the response of the one or the nine? Perhaps, he suggested, both responses were faithful. The Samaritan returned to thank the one who healed him. And the nine Jewish lepers continued on to do what Jesus the rabbi had instructed them to do: go and show themselves to the priest.

The biblical texts leave room for difference but not silence, Brosend said. “And to say we’re not supposed to take a stand, or I don’t want to jeopardize our nonprofit status or something like that is really avoiding the homiletical question in this season of our national life.”

Yet, such preaching does bring its perils. In one of the more high-profile examples, the Rev. George Regas, retired rector of All Saints Church in Pasadena, California, preached a sermon at All Saints just before the 2004 presidential election that the Internal Revenue Service initially said constituted intervention in the process. Regas imagined Jesus debating George W. Bush and John Kerry, and said people of faith could vote for either person. He also imagined Jesus telling Bush that the president’s doctrine of preemptive war was wrong and said that Bush-sponsored tax cuts “would break Jesus’ heart.”

The IRS opened a two-year investigation into the parish that concluded in September 2007 without challenging the parish’s tax-exempt status and without a threatened audit ever taking place.

As the election season careens to its Nov. 8 finish, preachers have a broader task than simply deciding what and how to preach. Budde said the assignment is this: “How to find a way for every voice to be heard, allow people to speak their own truth and then to allow the community to move forward in a way that is part of the reconciliation we need” both inside the faith community and in the wider world.

Read more about it

The Episcopal Church’s Election Engagement Toolkit is here and the accompanying website is here.

The Internal Revenue Service’s guide for election engagement activities, titled “Tax Guide for Churches and Religious Organizations,” is here.

The Pew Research Center for Religion & Public Life’s resource “Preaching Politics from the Pulpit” includes this question-and-answer section that unpacks the IRS rules.

The Nonprofit Vote website includes more resources on what churches legally can and cannot do during election season.

A 30-day cycle of prayer, called for by Forward Movement, began Oct. 6. The cycle includes weekly PDFs with prayers for each day. The entire cycle is available for download in a single PDF. The final prayer is for Nov. 9. The downloads, one in English and another in Spanish, are here.

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is an editor/reporter for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu