Archbishops of York medieval records digitized, available onlinePosted Mar 1, 2016 |

|

[Anglican Communion News Sservice] More than 10,000 individual handwritten parchment folios belonging to the Archbishops of York between 1225 and 1650 have been digitally scanned and are now being made available online. The York Registers, produced by the University of York, is said to be “one of the most important collections of historical materials to survive in England today.”

The papers record activity across the whole of the north of England and provide unique insights into ecclesiastical, political and cultural history over a period that witnessed the Black Death, the Wars of the Roses, the Reformation and the English Civil War.

Each record was individually assessed and treated by a specialist conservator before being scanned in what the university says was “a highly technical process” over the course of 15 months. In some cases, the documents were scanned using ultraviolet imaging, revealing text that had remain unseen for hundreds of years.

“The launch of the Archbishops’ Registers website brings to fruition a major project in the Digital Humanities, its content and method being of truly international importance,” Professor Mark Ormrod, the university’s Dean of arts and humanities, said.

“Bringing together the very best of modern technologies with the highest traditions of academic research, the continuing work on the Archbishops’ Registers will ensure free and remote access to the wealth of information and interest contained in these priceless historical documents.”

The records cast new light on historic events and the university has produced summaries of some of these to promote the new website, which can be found here.

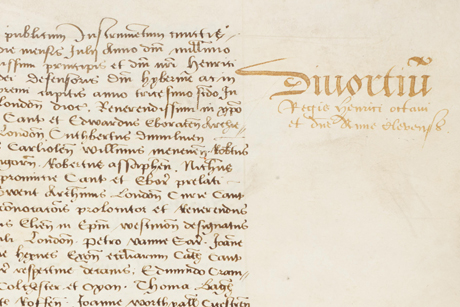

The Divorce from Anne of Cleves: 1540

A margin headline from the York Registers reads “Divortiu(m) Regis Henrici octaui et d(omi)ne Anne Clevensis” – the divorce of Henry VIII and Ann of Cleves

The Archbishops of York were closely associated with the Tudor monarchy – Thomas Wolsey being Archbishop of York from 1514 until his arrest at Cawood (one of his official residences as Archbishop) in 1530.

The Register of his successor, Edward Lee, contains copies of the official evidence relating to Henry VIII’s divorce from his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. Henry and Anne were married in January 1540, though the statements in Lee’s register show that this was not a marriage that Henry was particularly enamored with. The Register records Henry saying, after his first meeting with Anne, “I see no such thing in her, as haith benn shewed me of her and am ashamed that men haith so praesed her as they have dooun, and I like her nott”.

Lee’s Register also contains a contemporary copy of the famous final letter from Thomas Cromwell. Henry blamed Cromwell for organizing the marriage with Anne, and with Cromwell’s enemies emboldened by this loss of patronage, he suffered a spectacular fall from grace ending with his execution in July 1540.

In his final letter to Henry, Cromwell sets out all of Henry’s objections to the marriage in graphic detail: “I have felt her belly and her brestes, and therby as I can Judge, she shulde be no mayde, which strake me so to the harte whan I felte them that I hadd nother will nor courrage to procede any further in other matters.”

Cromwell signs his letter: “with the hevy hert and trembling hande of your hieghnes most hevye and most miserable Prysoner and pore slave Thomas Crumwell most gracious Prince I crye for mercy mercy mercy.”

Impact of the Black Death: 1349

The Register for Archbishop Zouche contains thousands of entries relating to men becoming clergy in the Diocese at various levels – acolyte being the lowest, priests being the highest.

Archbishop Zouche issued a warning throughout the Diocese in July 1348 (when the Black Death was raging further south) of “great mortalities, pestilences and infections of the air”.

The “Great Mortality”, as it was then known, entered Yorkshire in February 1349, and quickly spread through the Diocese. The clergy were on the front line of the disease, bringing comfort to the dying, hearing final confessions and organizing burials. This put them at a greater risk of infection.

It’s no surprise to find that Zouche’s Register shows a massive rise in new clergy over the period – some being recruited before the arrival of plague in a clerical recruitment drive, but many once plague had arrived, replacing those who had been killed by it. In 1346, 111 priests and 337 acolytes were recruited. In 1349, 299 priests and 683 acolytes are named, with 166 priests being created in one session alone in February 1350. Estimates suggest that the death rate of clergy in some parts of the Archdiocese could have been as high as 48 per cent.

The case of Thomas de Whalley: 1280

Thomas de Whalley was the Abbot of Selby Abbey. Selby was visited by Archbishop Wickwane around the 8 January 1280. De Whalley was a known troublemaker, and had actually been removed as Abbot of Selby in 1264.

On this occasion, Wickwane found that de Whalley “does not preach . . . does not teach . . . does not correct faults [in others] . . . never sleeps in the dormitory . . . does not visit the sick . . . is rarely out of bed to hear matins . . . eats meat with laymen in his manor . . . ignores the orders of the holy father and his archbishop . . …has negligent and bad habits and is, overall, incorrigible.”

The Visitation also found that de Whalley had managed to lose money by not collecting local taxes due to the monastery; was “noted for incontinence” with two local women – one of whom had apparently borne him a child.

Finally, it was found that de Whalley had procured at great expense the services of one Elyam Fanuelle, a “sorcerer and fortune-teller” in the search for the body of his brother, who had drowned in the river Ouse. Unsurprisingly, de Whalley was excommunicated.

Little more is heard of Thomas de Whalley, save the fact that in 1281 he was reported to have renounced his orders and had, effectively, gone on the run.

Social Menu