Detroit’s historically black St. Matthew’s added to ‘Freedom Network’National Park Service recognizes 170-year-old congregation’s Underground Railroad activismPosted Feb 25, 2016 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] Before Harriet Tubman escaped slavery, before Abraham Lincoln was elected to Congress and before Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, members of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church were helping slaves escape across the Detroit River to freedom in Canada.

Founded in 1846 above a blacksmith’s shop, St. Matthew’s is among the oldest historically black congregations in the Episcopal Church and in the nation, and was a center of local abolitionist activism and community organizing.

Yet that aspect of the church’s past went relatively unrecognized until 2015, when the National Park Service added St. Matthew’s to its National Network to Freedom.

“We found that it (St. Matthew’s) makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the Underground Railroad in American history … (and we) commend you on your dedication to this important aspect of our history,” Diane Miller, network national program manager, wrote in a June 4 letter announcing the award of the designation.

Senior Warden Philip Carrington, the Rev. Canon Robert W. Alltop, Dr. Richard E Smith and Junior Warden Rudolph Markoe.

For fourth-generation St. Matthew’s parishioner Dr. Richard E. Smith, who applied for the status, the quest to highlight the church’s storied past was a labor of love and long overdue. For nearly two decades, he wove together details of its proud history of community service and social activism.

“We always heard bits and pieces about the church’s history, but there was no written record,” Smith told the Episcopal News Service recently.

A time capsule offers a past and future glimpse

The unearthing of a time capsule in 1998, planted by church members some 70 years earlier at the site of the congregation’s second location at St. Antoine and Elizabeth Streets, yielded a written record of what previously had been oral history passed among generations, he said.

It also offered a glimpse into the city’s past. Those documents became part of the permanent collection of the Charles Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, Smith said.

“As a doctor, I deal in facts,” said Smith, an obstetrician-gynecologist, and vice president of Henry Ford Hospital Physician Outreach. “I began gathering information to put into a timeline for the church, along with family history and other information.”

Among other significant events, Smith’s timeline reveals that:

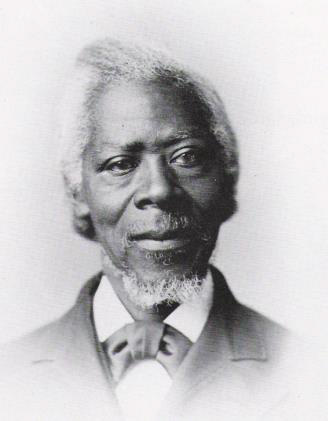

- Nine years after Michigan became the 26th state in the union, 13 years after slavery was abolished in Canada and nearly 40 years after slavery was abolished in Michigan, St. Matthew’s was organized as a mission congregation by the Rev. William Monroe and local businessman William Lambert, who served as warden.

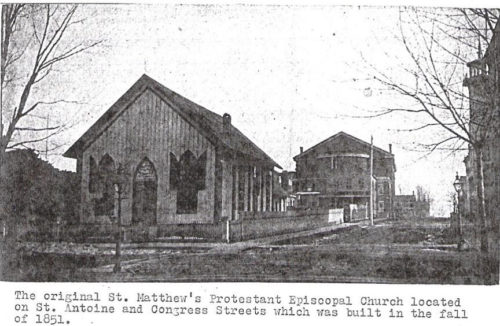

- Two years later, Lambert was elected a delegate to the National Convention of Colored Citizens held in Cleveland, at which Frederick Douglass was elected convention president. The same year, a city lot at the corner of St. Antoine and Congress was purchased to build the church and taxes of $2.22 paid to the state and county for the church.

- Over the next decade, nearly 40,000 fugitive slaves would pass through Detroit under the support and guidance of Lambert and others, including other churches in the city. “Everyone was working together, helping one another,” Smith said.

Roy Finkenbine, vice chair of the Michigan Freedom Trail Commission, said St. Matthew’s was one of three churches in Detroit’s pre-Civil War black community that actively aided freedom-seekers.

Lambert, known as “the father of St. Matthew’s,” founded the Colored Vigilant Committee, “essentially an all-purpose organization to help freedom-seekers get to Canada,” he said.

“It was all black in membership. They worked with select whites in the city and on the fringes of the city who would filter people to the committee. They did everything from raising funds to feeding (and) clothing people, providing medical care, hiding them in barns on the east side (and) getting them across the river late at night in skiffs hidden under the docks. They even offered legal representation.

“It was an illegal activity and one that was particularly dangerous after 1850,” he said.

A surprising revelation for junior warden Rudolph Markoe, a second-generation and lifelong St. Matthew’s member, was finding out “that we didn’t actually have a building for a stretch of time because many people left for Canada and California because of the threat of kidnapping and arrest.”

That was after the government passed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, another in a series of federal laws allowing for capture and return of runaway slaves, and harsh penalties imposed against the slaves and anyone who helped them. Enforcement of the law often facilitated kidnapping and enslaving of free people of color, prompting many to flee to Canada. The Rev. William Monroe emigrated to Liberia to establish an Episcopal mission. During that time, remaining St. Matthew’s members met at Christ Church Detroit, and their building was sold to a Jewish congregation, Shaary Zedek. The St. Matthew’s Mission Fund was established, pooling money to assist newcomers and later to build the next church.

Other highlights of the church’s history include:

- In 1855, James Holly was ordained a deacon at St. Matthew’s, and he was the first of six clergy associated with the church to become bishops in the Episcopal Church, according to Smith. Holly was consecrated the first black bishop in the Episcopal Church and founded the Episcopal Church in Haiti, the largest missionary diocese in the Episcopal Church. Others include the Rt. Revs. G. Mott Williams; Quintin Primo Jr.; Orris Walker Jr.; Arthur Williams and Irving Mayson.

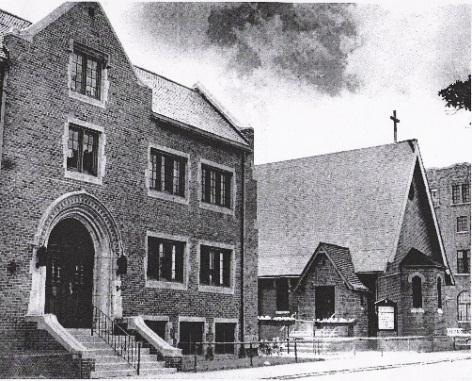

- The mission revived in the 1880s, at another site near downtown Detroit, and became “the center for improvement and service clubs.” By 1906 St. Matthew’s was so popular it had to limit participants, according to Smith. A year later, the church attained parish status.

- After the turn of the century, the Detroit chapter of the NAACP was established at and met at St. Matthew’s.

- During the 1920s then-rector the Rev. Evard Daniel continued as a trendsetter, developing a relationship with automaker Henry Ford and facilitating the hiring of many African Americans for factory work during “the Great Migration” of blacks from the South. Located in Detroit’s “Paradise Valley,” a business and entertainment hub, church membership was reportedly 800 communicants, with 300 children in its Sunday school, according to a Dec. 11, 1926, Detroit Free Press article.

- Donors included Clara Ford, spouse of automaker Henry Ford and an occasional worshipper at the church.

- In 1926, Marian Anderson performed her first Detroit concert at the Nov. 1 dedication of St. Matthew’s new parish house; the time capsule was placed in the cornerstone. The famed opera singer returned in 1939 for a repeat performance at St. Matthew’s, after being barred from Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

- Markoe also underscored the church’s involvement as an early meeting place for the NAACP and its social activism in the 1925 landmark trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet, whose wife, Gladys Mitchell, was an active St. Matthew’s member.

“They sponsored fundraisers to raise money for Clarence Darrow to come and defend Sweet,” he said. In a case considered to be one of the most important civil rights trials of that decade, Darrow successfully defended Sweet, a black medical doctor, against murder charges after a crowd threatened to eject Sweet from the all-white neighborhood where he had purchased a home. During the scuffle, someone in the crowd was shot and killed.

Sweet’s acquittal was considered a milestone decision in asserting the rights of blacks to defend their person and property.

- In 1940, the Rev. Ricksford Meyers was called as rector of the church; his wife, Dr. Marjorie Peebles-Meyers, became the first African American woman to graduate from the Wayne State University Medical School and to integrate many local hospitals.

Urban renewal, a new location and a merger

Sweeping urban renewal and social change impacted the congregation over the next several decades. New freeway construction displaced Detroit’s Paradise Valley; church membership dwindled.

Yet the tradition of social activism remained intact; clergy participated in 1960s civil rights demonstrations locally and nationally. In 1971, because of declining membership and economic challenges, St. Matthew’s merged with and relocated to St. Joseph’s Church in the mid-city area of Detroit.

“It was a melding of two communities of faith, each with their own unique identities that worked together and made it a fascinating place,” according to the Rev. Kenneth Near, who has served at the church. St. Joseph’s was a center of anti-Vietnam War activism, he said.

In 1998, the former church building was razed to make way for the construction of Ford Field, the home of the Detroit Lions professional football team; the time capsule was removed and opened. Also removed was a city-designated historic plaque.

Finkenbine said receiving the National Park Service Freedom Network designation “for something like the Underground Railroad says something, particularly in the case of churches, about who and what an organization wants to be. The fact that people were taking a chance to assist people in need, that they were willing to put a higher law above the national law, says something about those folks. The desire to recognize that as part of your heritage says something about the institution today and how the institution wants to operate and to work with issues today.”

St. Matthew’s continues “hands-on ministry” with a Sunday morning breakfast program that feeds about 60 and other ministries “geared toward assisting or lending a hand or step up to people who, for whatever reason, have fallen on hard times or can’t quite navigate through life’s problems,” Markoe said.

He said he learned the church’s history “in doses through the years,” through the work of others, such as the late Lillian Southern, the church historian who died in January 2015, and through Smith.

“It makes you feel a certain pride … a certain responsibility to keep that tradition going because people long before me saw a need and were committed to changing it.”

The Union of Black Episcopalians National President Annette Buchanan said, “St. Matthews stands in the great tradition of our historically black churches, many of whom were born out of the struggle for racial justice.

“On Feb. 13 as we commemorated the feast day of blessed Absalom Jones, our first black priest, and his founding of our first black Episcopal church, St. Thomas African Episcopal Church, we appreciate the foundation that he laid of community outreach, advocacy, and evangelism which St. Matthews has proudly perpetuated.

“The Black Episcopal Church has been and will continue to be the conscience of our denomination reminding us of our baptismal covenant to respect the dignity of every human being.”

Finkenbine said it is extremely important to have historically African American churches recognized on the Network for Freedom “because all too frequently nothing of them remains in local communities. Many institutions have disappeared off the landscape over the 150 years since the Underground Railroad ended. Those churches which are still active and exist like St. Matthew’s have to carry the water, be symbolic of all that larger area of work that black communities and black churches did to help bring freedom.”

Smith agreed. His quest to uncover and to gain recognition of the St. Matthew’s story intersected with the stories of his own and other families, he said.

“My family is one of the oldest in Michigan; we were a part of a family group of freedom-seekers, black settlers who left Fredericksburg, Virginia, about 1845,” he told ENS. “For as far back as I remember, I heard stories of the Underground Railroad.”

His interest peaked after a relative gave him the family’s “original 1803 ‘free papers’ from Virginia,” he said. “In my efforts to document our history, I also researched the stories I heard about St. Matthew’s early history. I was further energized with the opening of the time capsule from the church building on St. Antoine.”

During his research he was inspired to press on by the words of co-founder Lambert:

“We hold our liberty more dearly than we do our lives, and we will organize and prepare ourselves with determination: live or die, sink or swim, we will never be taken back into slavery.

“We will never voluntarily separate ourselves from the slave population in the country, for they are our fathers and mothers, and sisters and brothers; their interest, their wrongs and their sufferings are ours. The injuries inflicted on them are alike inflicted on us. Therefore, it is our duty to aid and assist them in their attempts to obtain their liberty.”

– The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a correspondent for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu