A sainted life: Hiram Hisanori Kano turned internment camp into mission fieldPosted Jul 2, 2015 |

|

Taiko drummers perform at the July 1 Eucharist honoring the late Rev. Hiram Hisanori Kano. The 78th General Convention passed a resolution including Kano and others in “A Great Cloud of Witnesses: A Calendar of Commemorations.” Photo: Pat McCaughan/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service – Salt Lake City] The fierce thunder of taiko drums reminded worshippers at the July 1 Eucharist of the intensity of the life and witness of the late Rev. Hiram Hisanori Kano, who transformed his imprisonment in World War II internment camps into a mission field.

Asian Americans refer to the World War II camps that housed Japanese nationals, and Japanese Americans as concentration camps.

With the passage of Resolution A055, the 78th General Convention officially included commemorations for Kano and three other men and one woman in “A Great Cloud of Witnesses: A Calendar of Commemorations,” for use in the next triennium.

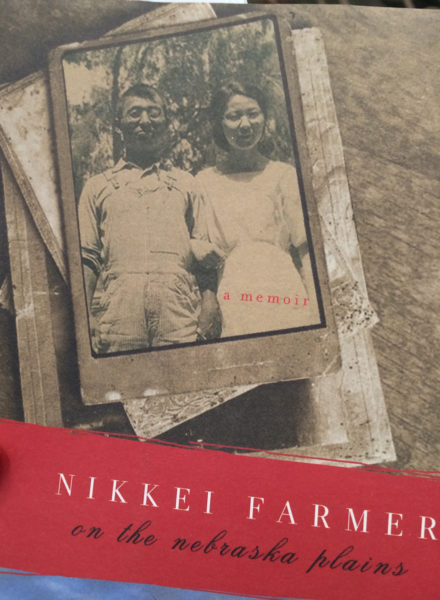

The late Rev. Hiram Hisanori Kano’s memoir, “Nikkei Farmer on the Nebraska Plains,” was published in English in 2010.

Bishop Scott Hayashi of Utah presided at the Eucharist that honored Kano, who died in 1988 just short of his 100th birthday. Oct. 24 will serve as the official day for the commemoration of Kano, who authored “Nikkei Farmer on the Nebraska Plains,” a memoir tracing his early life in Japan to his move to America (Nikkei refers to people in the Japanese diaspora). It included stories of his time in the various camps where more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent were forced to live during World War II. In the camps, Kano led worship, ministered to and taught those around him, including his jailers, other prisoners, and German prisoners of war.

“He was gone three years,” recalled his son Cyrus Kano, 94, who along with other family members and friends attended the convention worship service.

The Rev. Fred Vergara, the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society’s missioner for Asiamerica ministries, said it is important for voices and witness such as Kano’s to be commemorated and included in the church’s ongoing conversations to inspire future generations.

Adeline Kano, 87, said she watched the live-streamed Eucharist from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, in Fort Collins, Colorado, where her father had served occasionally in retirement.

Myrne Watrous, a St. Paul’s parishioner who attended the Salt Lake City convention Eucharist, said the honor was fitting. “If you look at the lives of saints, it was him,” she said of Kano, whom she knew. “He left a life of wealth to become a farmer in Nebraska and to preach the word of God, to talk the talk and walk the walk.”

Granddaughter Susan Kano said she was amazed at the size of worship and the commemoration. The only inkling she had of her grandfather’s role in the community came at a 50th wedding anniversary celebration for he and her grandmother, Aiko Ivy Kano. “People kept shaking my hand – hundreds of them – and saying ‘your grandfather is a saint,’” she recalled.

She said that he considered his time in the camps a gift to his ministry. “He had an amazing life,” she said.

The others included for liturgical commemoration in Resolution A055 were: Charles Raymond Barnes (who was commemorated at the July 2 Eucharist), Artemisia Bowden, Albert Schweitzer and Dag Hammarskjold.

Cyrus Kano, a retired mechanical engineer who lives in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, said his father would want to be remembered “as a man of God.”

About his camp experiences, Kano turned adversity into fertile mission territory: “He said, well, God put me here, what does he want me to do?” recalled his son.

In addition to organizing a camp college where he taught English and other courses, he conducted nature studies and led worship services while incarcerated.

Kano immigrated to the United States after a youthful encounter with William Jennings Bryan in his native Japan stirred his sense of adventure, according to his daughter, Adeline Kano. His background was that of privilege: “My grandfather was the governor of the prefecture of Kagoshina,” explained Kano, 87, during a telephone interview from her Fort Collins home.

Initially, Kano earned a master’s degree in agricultural economics at the University of Nebraska, and just as quickly became an activist and leader among the Japanese “Issei” or the first-generation Japanese-American community, many of whom had come to farm or to work on the railroads.

The Rt. Rev. George Allen Beecher, then bishop of the missionary Diocese of Western Nebraska, heard about Kano’s activism in 1921, when state lawmakers were considering legislation that would preclude Japanese immigrants from owning or inheriting land, or even leasing it for more than two years. The bill also would have forbidden them from owning shares of stock in companies they had formed.

Kano and Beecher met and traveled together to the state capitol to address lawmakers, who eventually passed a less restrictive measure, according to Kano’s memoir.

Beecher persuaded Kano several years later to become a missionary to the Japanese-American community, estimated at about 600. In 1925, Kano complied and the family moved to North Platte. He was ordained a deacon three years later and served two mission congregations, St. Mary’s Church in Mitchell and St. George’s Church in North Platte. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1936.

— The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a member of the Episcopal News Service team reporting about the 78th General Convention.

Social Menu