Episcopalians urged to act to protect the Arctic National Wildlife RefugePosted Apr 20, 2015 |

|

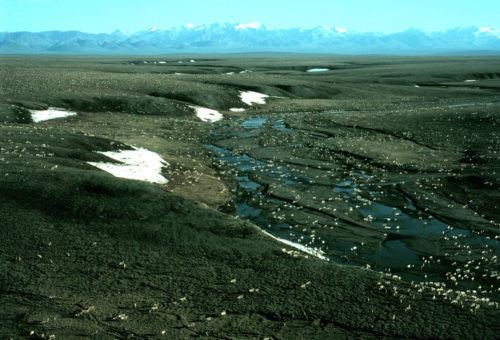

Porcupine caribou herd in the 1002 area of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain, with the Brooks Range mountains in the distance to the south. Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

[Episcopal News Service] To energy companies the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, particularly its 1.5-million acre coastal plain, is a potential oil and natural gas bonanza. To the Gwich’in, the indigenous people who for centuries have called it home, it’s sacred.

This conflict has fueled for more than 30 years a contentious debate over whether this coastal plain should be opened to oil drilling or kept as an unspoiled habitat. The biologically diverse ecosystem is home to Porcupine caribou, polar bears, gray wolves, Dall sheep, musk oxen, 42 fish species and more than 200 bird species.

It is an ongoing debate only U.S. Congress can resolve, and once again it’s on the radar with the recent introduction of a bipartisan bill in the House that would designate the coastal plain a wilderness, permanently making drilling off limits. On April 21 – the day before Earth Day – as part of the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society’s 30 Days of Action campaign, Episcopalians will be encouraged to advocate for coastal plain’s wilderness designation.

Sitting at the top of the Arctic refuge on the coast of the Beaufort Sea, just east of the Prudhoe Bay oil field, the coastal plain is the calving ground for the Porcupine caribou herd, so named for the nearby Porcupine River.

The Gwich’in people, who have depended on the caribou for thousands of years, refer to the coastal plain as “the sacred place where life begins.”

The Gwich’in, 90 percent of them Episcopalians, have opposed their conservative state officials to protect the coastal plain from development and oil drilling. The wilderness designation also would protect the cultural and subsistence rights of the Gwich’in people.

“We are dependent on the Porcupine caribou herd for our survival and if the health of that herd is threatened, it threatens our way of life. One day we’ll have to go back to simpler living and we won’t have that if the herd is gone,” said Princess Daazhraii Johnson, a lifelong Episcopalian and former executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee.

In 1988, Gwich’in from across the Gwich’in Nation gathered in Arctic Village, Alaska, on the southeast corner of the Arctic refuge, for a meeting unlike any in more than a century. They came by chartered bush planes from 15 remote villages scattered across northeast Alaska and northwest Canada – villages located on the caribou’s migratory route – and formed the Gwich’in Steering Committee, explained Johnson, in a telephone call with Episcopal News Service from St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Fairbanks.

“We hadn’t had a gathering like this in 100 years, but this was such a serious discussion,” she said. “I was 14 at the time. My family was there for the gathering. I was not there but the ramifications have had a great impact on my life.”

Ninety-five percent of Alaska’s North Slope already is open for development, said Johnson. To open the coastal plain would resonate throughout the world.

“Getting into the refuge is symbolic. … It will send a message that there are no permanently protected places, [that] no place is sacred,” she said. “Our thirst for extracting oil is going to trump that.”

Throughout the debate, indigenous voices have been sidelined, with native cultures being characterized as simple-minded – dismissing the fact that indigenous people have lived and been caretakers of their ancestral land in the Arctic for centuries, and have suffered firsthand the effects of climate change.

“I feel very grateful because The Episcopal Church has always elevated that voice,” she said.

The church’s involvement

The Episcopal Church has been in Alaska since the mid-1800s, with the Gwich’in almost exclusively members of the church, said the Rev. Scott Fisher, rector of St. Matthew’s, who participated in the phone interview from his parish.

The Episcopal Church’s support for protecting the Arctic refuge, he explained, began in the Diocese of Alaska, where Gwich’in clergy first introduced it, and then brought the matter before General Convention.

In 1991, General Convention passed a resolution opposing oil development in the Arctic refuge, and committed itself to work for legislation “to improve energy efficiency and conservation so that drilling in this pristine area would not be necessary.”

Gwitch’in clergy and Alaska Bishop Mark Lattime gather for a photo at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Fairbanks in June 2014 following an historic Takudh Eucharist. Photo courtesy of Scott Fisher.

“The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is more than a wilderness preserve established to protect against the loss of delicate Arctic ecosystems, it is also a sacred place: the spiritual and cultural home of the Gwich’in people,” wrote Alaska Bishop Mark Lattime in an e-mail to ENS, when asked about the importance of The Episcopal Church’s continued support.

“Every Christian is called to seek justice and peace among all people, and to respect the dignity of every human being. This is the sacred oath of Baptism. As bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Alaska, the church that most Gwich’in identify as home, I call upon people of faith, especially Episcopalians, to listen to the voice of the Gwich’in people as they seek to protect not only the environment and peace of their home, but the respect and dignity of their way of life.”

In 2005 The Episcopal Church partnered with the Gwich’in Steering Committee on a report on the human rights implications of drilling in the refuge.

Historical political perspective

In 1960, a year after Alaska became a state, President Dwight Eisenhower set aside 8.6 million acres in the North Slope and designated it the “Arctic National Wildlife Range.”

Crises in the Middle East in the 1970s, the 1973-74 OPEC rebellion and the 1979 Iran revolution dramatically increased oil prices, and drilling in Prudhoe Bay, which previously had been too expensive, became profitable. It is now the largest oil field in North America.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter and the Congress, under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, more than doubled the area for preservation, renaming it the “Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.”

Although the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act required the state to put the subsistence use of indigenous people above all else and prohibited oil and gas exploration in the northeast corner along the coastal plain, it left the possibility for future exploration in the hands of Congress.

In 1987, when Ronald Reagan was president, the U.S. Department of the Interior recommended that Congress open the coastal plain to drilling. President George H.W. Bush, who began is presidency in 1989, made drilling in the refuge a centerpiece of his energy policy, and in early March 1989 a Senate committee approved leasing in the coastal plain. On March 24, 1989, the Exxon Valdez spilled more than 11 million gallons of crude oil in Prince William Sound.

When Iraq invaded Kuwait and later set fire to its oil fields, the possibility of drilling in the Arctic refuge again gained steam and eventually found its way into a budget package vetoed by President Bill Clinton. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks and a rise in oil prices, President George W. Bush, like his father, thought drilling on the coastal plain should be part the country’s energy policy.

In early January of this year, the bipartisan Udall-Eisenhower Arctic Wilderness Act was introduced in the U.S. House. If passed, it would permanently protect 12.28 million acres – including the coastal plain. On Jan. 25, President Barack Obama endorsed the bill. If passed, the area would become the largest wilderness-protected area since the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964.

Continued advocacy

The Episcopal Church joined other faith communities in thanking Obama for taking action that “represents a critical step in protecting a sacred part of God’s creation, and we thank you for working to safeguard this national treasure.”

“We are involved in this important advocacy not only because of our concern for stewardship of God’s creation, but also because we stand in solidarity with our Gwich’in brothers and sisters who live in the Arctic and depend upon the Porcupine caribou herd for their daily subsistence,” said Jayce Hafner, domestic policy analyst for the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society.

The Episcopal Church at its 77th General Convention in 2012 passed legislation saying it “stands in solidarity with those communities who bear the burdens of global climate change,” including indigenous people.

“The Episcopal Church, the larger faith-based community, and others have been really supportive of the Gwich’in, but to me there is a bigger, broader picture,” said Johnson. “We need a more compassionate economy and we need to think about climate change – the most affected people being indigenous, but all people are affected.”

Alaska’s indigenous people have already begun to experience significant changes in their natural environment, explained Johnson during a panel on the regional impacts of climate change. The panel was part of a March 24 forum in Los Angeles to raise awareness about the effects of climate change across The Episcopal Church.

“The Arctic is one of the fastest warming places on the planet and we’re seeing the melting of the ice sheets, our glaciers are disappearing, the permafrost is melting, [and there is] coastal erosion,” said Johnson, during the forum. “We have entire communities that are having to be relocated.”

Climate change is the gradual change in global temperature caused by accumulation of greenhouse gases that trap heat in the atmosphere, altering the earth’s temperature. Some areas are getting warmer, as others are getting colder. For example, the mainland United States experienced the coldest winter on record since formal record keeping began in the late 1800s, whereas Alaska experienced an unseasonably warm winter.

Protecting the coastal plain of the Arctic is particularly important right now, said Hafner, as the planet confronts the carbon emissions produced by fossil fuel extraction, which, in turn, contribute to climate change.

“We’re having these conversations at local levels in parish communities, at the national level with the President’s Clean Power Plan, and at the international level with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations that will culminate in Paris this December,” she said.

The goal of the Paris conference is to forge an international agreement aimed at transitioning the world toward resilient, low-carbon societies and economies. If accomplished, it would be the first-ever binding, international treaty in 20 years of United Nations climate talks, and would affect developed and developing countries.

— Lynette Wilson is a writer and editor for Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu