Coal Country Hangout connects youth, communityDeacon devotes decades to building connectionsPosted Feb 10, 2015 |

|

Coal Country preschoolers take part in a field trip led by Beth Garner, an education specialist with the Pennsylvania Department of Natural Resources, to Prince Gallitzin State Park. Photo: Lynette Wilson/ENS

[Episcopal News Service – Northern Cambria, Pennsylvania] Against the low-hanging, late-October morning sky the stone building with the red metal roof housing the Coal Country Hangout Youth Center casts a stark profile at the corner of Maple Avenue and Cottonwood Street in this rural community an hour and 40 minutes’ drive northeast of Pittsburgh in the Allegheny Mountains.

On the inside, however, bright-colored murals hang on paneled walls and the sound of babies and toddlers busy playing and learning fill the space, in what is the only day care center and one of two preschools serving Northern Cambria, a rural bedroom community, and Altoona, Johnstown and Indiana, each town a 40- to-50-minutes away.

“Fifty percent of the children in day care have parents that work in these three communities; Northern Cambria is the hub,” said the Rev. Ann Staples, an Episcopal deacon who co-founded and has served as Coal Country’s executive director since 1996.

In addition to operating the day care in a county where 14.9 percent of the population lives in poverty and providing early childhood education in one of Pennsylvania’s poorest school districts, Coal Country operates a program for teens and young adults on Friday and Saturday nights in a converted sanctuary, with a basketball court, billiards and table tennis on the main level, and a small computer laboratory in the balcony.

“There are no facilities for kids anywhere in this area,” said Staples. “It is rural, it is isolated, it’s a good 35-40 minute drive to anything resembling recreational facilities, and that’s why we founded Coal Country – so they’d have a place to get off the streets, have a good time under supervision.”

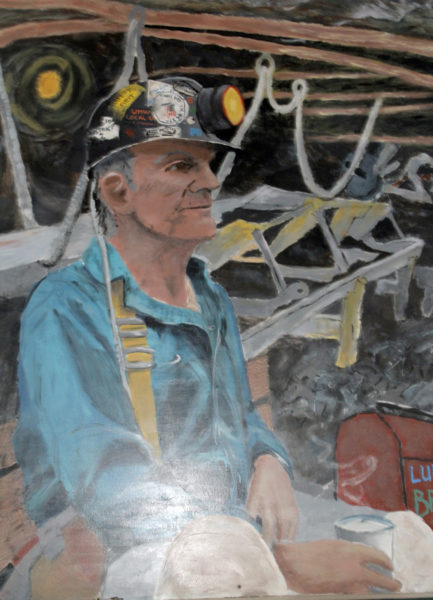

Portraits of miners painted by students hang on the walls of the Coal Country Hangout Youth Center. Photo: Lynette Wilson/ENS

A safe, drug-free environment where youth can be with their peers is important, said Rebecca Pupo, the principal of Northern Cambria High School, during an interview with Episcopal News Service in her office, adding that drug-sniffing dogs recently swept the school for marijuana and heroin, local drugs of choice.

“(Coal Country) definitely serves these kids and they need the positive social connections,” she said. “Some go home to an empty house … the closest shopping mall is a 40-minute drive. Unless a student is involved in sports or other extracurricular activities, there’s nowhere to go.

“Not everyone is a football-Friday person.”

An independent nonprofit organization and supported ministry of the Diocese of Pittsburgh, the center’s name is a homage to the coal industry’s longstanding, historical importance to the region’s economy and its identity. Its mission is to support families by providing access to affordable childcare, to promote healthy family behaviors, and to help prevent youth delinquency.

Operating in an economically depressed, geographically isolated region where ethnic bonds date back to the late 19th century, its programs take a holistic educational and cultural approach to address the spiritual and emotional trauma caused by the coal industry’s collapse.

“It’s Appalachia, they are very tight-knit and very wary of outsiders – they know instantly, probably before you open your mouth, that you are not from around there,” said Pittsburgh Bishop Dorsey McConnell, in an interview with ENS in his suburban Pittsburgh office. “So in that sense Ann’s been a missionary, because she’s been able to insert herself in that community and over time, she’s gained the affection and trust, I think, of everyone in that region.”

Raised in Corpus Christi, Texas, Staples studied music with an emphasis in piano performance in the early 1950s at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, spent a year traveling in Europe, and pursued a doctorate in musicology at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. A mother of six, grandmother to 13, she taught college in New York and then for 17 years at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 40 minutes west of Northern Cambria.

In Indiana, Staples was a member of Christ Episcopal Church, when in 1984 the Diocese of Pittsburgh ordained her a deacon. She has served parishes throughout Pennsylvania, including Verona, Murrysville, Indiana, Patton and Northern Cambria, where she continues to serve St. Thomas Episcopal Church.

Staples models her ministry after that of the Rev. Curtis Junker, her college chaplain at SMU, where she left Methodism and joined the Canterbury Club.

Junker moved comfortably between Dallas society and people on the street, and he encouraged students to tag along while he carried out his ministry. “That experience made all the difference in the world to me,” said Staples. “For me it was a model of ministry, the way it ought to be. Sitting in the church holed up – it doesn’t work.”

Staples has lived out Junker’s example by being a visible presence in the community, by getting to know elected officials, businessmen, community developers, teachers and school administrators, and people on the street. Around town, everyone calls her “Deacon Ann.”

“Whenever Ann walks into a room or an office … people get up from their chairs to greet her,” said McConnell. “She just has enormous respect; the reason is the people of Northern Cambria are not a project to her – they are human beings, made by God and redeemed by Jesus Christ.

“She has spent the time that she has been up there cultivating relationships across the board. That has been strategic, to a certain degree, but the fact is also she’s just committed to strengthening the human bonds in those communities in any way that she can do, and of course those communities are deeply relational.”

The Rev. Ann Staples, an Episcopal deacon, describes on a map the area of rural Pennsylvania served by the Coal Country Hangout Youth Center. Photo: Lynette Wilson/ENS

The borough of Northern Cambria, population 5,000, was incorporated in 2000 when the towns of Spangler and Barnesboro merged. It was a move intended to qualify the town for federal aid but did not. In fact, the borough is so small the U.S. Census Bureau includes it in the statistics for Johnstown, population 20,000.

Staples arrived in Northern Cambria to serve St. Thomas Episcopal Church in September 1993, the same time as Coal Country co-founder Pastor Marty Cartmell arrived at St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church. During the summer of 1994, as both women were still getting to know the community, each witnessed teenagers’ boredom-fueled antics.

“We did a lot of running around and seeing what the place was like and we discovered on summer nights that kids were just all over the town, just all over, everywhere,” said Staples over a stromboli at Hubcaps Grill, a pizzeria across from Cambria Heights High School just outside Patton, one of four high schools she assists in implementing Coal Country’s experiential learning program.

The teens had “invented a lovely game at the main intersection in town at the light,” Staples said. “Highway 219 comes up a slope, makes a total left-hand turn and proceeds out of town. The kids all got together and sat down on the highway and made a wall across the highway just at the point where the trucks coming up 219 had to rev their motors … to get around that curve. And here’s a wall of kids – they’d blow their truck horns, the kids would jump up screaming,” she continued, somewhat amused.

“Marty and I both saw this, and said, ‘My God, these kids have got to have something to do,’ and that’s where it started right there.” She stressed that the kids were never really in danger. But the human wall was more indicative of the “mindless, generalized vandalism” evidenced in town.

Coal Country began with the teen program in 1996. In 2000 the organization bought the building, a decommissioned Roman Catholic church – one of 13 closed that year by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown – for $1.

“We started with a teen program before we got the building we’re in now, for the first four years ,… then created the day care, preschool, and then established the experiential education component,” said Staples.

Experiential education

Regional high school graduation rates are high, but the percentage people who go to college drops dramatically. Mining jobs pay in the $60,000 range; the median household income is $41,730. The area is home to a large percentage of elderly people looking for a lower cost of living, and low-income people who rely on social services.

The experiential education program provides for creative projects and fieldwork, and students who participate in Coal Country’s experiential education program tend to score higher on standardized tests, and 100 percent go on to college.

“We looked at graduation rates four all four school districts, 94-97 percent, post-secondary drops 30 to 35 percent in all four school district, said Staples. “It goes to prove a point: you cannot simply do it while sitting in a classroom with a textbook, without this kind of experience in the field.

“We’re proud of that; we think it’s an interesting statistic.”

Experiential education includes, arts, local history, environmental education and contemporary issues, which together bring awareness, not just to the students who participate, but the community, of a sense of place, not only of the region’s coal production and role in building American cities, but its significance in American history.

“The things that I cherish most about growing up in Texas wouldn’t have happened anywhere else,” said Staples, who maintains a Texas lilt complete with the cuss words she grew up with. “Any place where you are is important, it pinpoints all these things you grow up to be.”

A stone and ceramic monument made by students participating in Coal Country’s experiential education program marks Kittanning Path, an old trail that crosses northern Cambria County. Photo: Lynette Wilson/ENS

Long before the industrial revolution, Native Americans and European settlers occupied the region. Through arts grants, students have erected stone and ceramic monuments highlighting battles, trade and settlers’ routes. For instance, the monument at Kittanning Path marks a Native American trail that cut east and west through western Pennsylvania used by Europeans to settle the region and beyond.

“This was the major highway for settlers in the century prior to the U.S. becoming a country, and we think history is important,” said Staples, while driving the winding rural Allegheny Mountain roads in her red 2003 Saturn, odometer reading more than 200,000 miles, the radio tuned to classical music.

In American history students learn about what happened on the Eastern Seaboard, “where all the action was. Kids grow up without knowing what happened here or that it had any value,” she added.

Deacon Ann Staples, artist Michael Allison and teacher Kady Manifest, discuss a student art project during a meeting at Cambria Heights High School. Lynette Wilson/ENS

Northern Cambria High School social studies teacher Karen Bowman has led students in four local history projects, including a documentary film project “We Never Got the Welcome Home: Vietnam Vets of Western PA Remembered,” the latter completed with the help of a $10,000 grant from the History Channel.

Produced by 14 students, the film features more than two dozen area Vietnam vets, who reflect on their return home from the war nearly 30 years earlier, and how their lives and the region had changed. Cambria County, population 140,000, has a high rate of military service and is home to more than 13,000 veterans.

In teacher Ron Yuhas’ biology class an environmental grant from Coal Country allowed students to go out into the field to measure water quality in the West Branch Susquehanna to assess the damage from acid mine drainage.

“The kids are outdoorsmen and sportsmen and concerned with water quality,” said Yuhas, adding that a new grant will allow for continued monitoring.

The school district is focused on getting students prepared for vocational education and college, and there’s not always funding or time for electives, said Pupo, the school’s principal.

“Really we need to ensure that they are going to be productive members of society. Some have big dreams of moving to other places,” said Pupo. “The challenge is, as they walk out of here, they compete for jobs in the real world.”

Pennsylvania’s ‘energy county’

Energy news dominates the headlines in Pittsburgh and the local papers: the shale boom, for instance, and events such as an October conference sponsored by the local American Middle East Institute where Oman’s minister of oil and gas praised fracking. Cambria County’s government website bills it as Pennsylvania’s Energy County.” The Obama administration’s so-called “war on coal,” doesn’t make him popular in the region.

Signs that coal’s slipping in importance: the giant wind turbines, churning out electricity throughout the region.

“Gamesa Energy developed the entire ridge across the central part of the state for wind energy purposes,” said Staples. “That caused major concern for people trying to maintain the coal mines … a new form of energy with nothing to do with coal.”

At the start of the 20th century, in 1901, there were 130 significant coal mines in Cambria County; the mines were at their most productive in ‘10s and ‘20s, supplying energy at a time when the U.S. steel industry increased its output by more than 150 percent, becoming the world’s largest steel producer.

In the 1970s, as the United States moved from being the world’s largest exporter to the world’s largest importer of steel, the ripple effects were felt throughout Appalachia. In the 1990s, the remaining union mines closed and miner salaries plunged.

Ethnic bonds

In the late 19th century Europeans emigrated in large numbers to work in the mines.

“When they started coming and they would emigrate in huge batches. Italy, Poland, Wales … this town was totally founded by immigrants,” said Staples. “And they weren’t the kind of people who were people of position back home, so they came here because they could get a job in mining and they formed little cliques based on ethnicity. So much so that in every town in northern Cambria there was a little Catholic Church: one that was Italian, one that was Polish, one that was English, one that was Welsh.”

“Fourteen (in all), because every immigrant group that came had a church,” she said, adding that at one point, 94 percent of the community was Roman Catholic.

In 2000, the same year Barnesboro and Spangler merged, the Roman Catholic diocese closed all but one of its 14 ethnic parishes, another blow to the region’s cultural identity. Staples said the closings were painful, but “In the end it was very pragmatic, (the bishop) picked the parish that was in the best physical condition, and made it very clear that that was why.”

The Young Men’s Polish Legion, the Slovak Club, the Sons of Italy, and other men’s clubs remain open.

Quiet streets

Aside from the occasional sound of heavy trucks roaring up Crawford Avenue to where it intersects Highway 219, or Philadelphia Avenue as it’s called in town, the streets are quiet.

Mom-and-pop shops – a tiny grocery that specializes in lottery tickets, Italian restaurants and pizzerias, a liquor store, a shoe store, a public library, a home appliance store – occupy retail space on Crawford and Philadelphia avenues, the core of the borough’s downtown.

On Oct. 30, Coal Country board members gathered at the center to talk about its importance to the community in a conversation that eventually turned nostalgic and led to talk about creating jobs and opportunities for young people.

That same day Cambria County had been dealt another blow – the loss of more than 400 jobs – when it was announced that a Virginia-based coal mining company would sell off “a large chunk” of its Pennsylvania assets to a Kittanning-based company.

Later, young people arrived at Coal Country to decorate for the following night’s Halloween dance. Phillip “Flip” Schlereth, who’s been coming for six years, was there, as was his friend Anthony Reid, who moved to Northern Cambria from Texas a year or so ago and started coming to Coal Country at Flip’s invitation.

They come to hang out with friends and meet new people, Reid said.

Julia DeLoatch, 20, was there along with her 16-year-old sister and 17-year-old brother. DeLoatch, who works at Dairy Queen with a goal to get out of town, came to help set up for the dance, but also to encourage her sister and brother to stay out of trouble, she said.

When Staples and Cartmell, who later parted ways with the organization, first opened the doors, no one came; it took time to build trust among the community and the youth. The fact that 40 to 50 youth now come on weekend nights is a sign that the people are comforted and healed, said McConnell, the bishop of Pittsburgh. “Missional communities are always relational communities … that the public gospel, which is to say that what is taking place in that youth hangout center, is definitely growing out of a heart that people have come to trust.

“The fact is you don’t have to prove yourself that you are a certain way to get into that youth center, you just walk in. …,There are certain expectations because I think that Ann is really interested in seeing kids grow up into the people that God wants them to become.”

In a community where the majority of the signs indicate it’s a place that has been beaten down, there exists a kind of “cultural accommodation of despair” and the future seems like a big challenge, said McConnell.

“But then you walk into that place and you see what’s going on in there and it gives everybody a reason to hope. I think that’s one of the reasons she’s precious in that community – you don’t to have have a kid in that program in order to be proud of it,” said McConnell. “They can point at her and say, ‘We’re not dead yet. See there is some life here.’ ”

– Lynette Wilson is an editor/reporter for Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu